In rail transport, a derailment occurs when a rail vehicle such as a train comes off its rails. Although many derailments are minor, all result in temporary disruption of the proper operation of the railway system and they are a potentially serious hazard.

The Ufton Nervet rail crash occurred on 6 November 2004 when a train collided with a stationary car on a level crossing on the Reading–Taunton line near Ufton Nervet, Berkshire, England. The collision derailed the train, and seven people—including the drivers of the train and the car—were killed.

On 6 January 1968, a low-loader transporter carrying a 120-ton electrical transformer was struck by a British Rail express train on a recently installed automatic level crossing at Hixon, Staffordshire, England.

The Amagasaki derailment occurred in Amagasaki, Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan, on 25 April 2005 at 09:19 local time, just after the local rush hour. It occurred when a seven-car commuter train came off the tracks on West Japan Railway Company's Fukuchiyama Line in just before Amagasaki on its way for Dōshisha-mae via the JR Tōzai Line and the Gakkentoshi Line, and the front two cars rammed into an apartment building. The first car slid into the first-floor parking garage and as a result took days to remove, while the second slammed into the corner of the building, being crushed into an L-shaped against it by the weight of the remaining cars. Of the roughly 700 passengers on board at the time of the crash, 106 passengers, in addition to the driver, were killed and 562 others injured. Most survivors and witnesses claimed that the train appeared to have been travelling too fast. The incident was Japan's most serious since the 1963 Tsurumi rail accident.

The Hull–Scarborough line, also known as the Yorkshire Coast Line, is a railway line in Yorkshire, England that is used primarily for passenger traffic. It runs northwards from Hull Paragon via Beverley and Driffield to Bridlington, joining the York–Scarborough line at a junction near Seamer before terminating at Scarborough railway station.

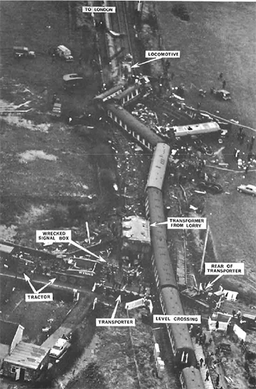

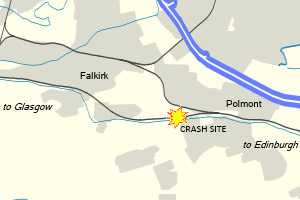

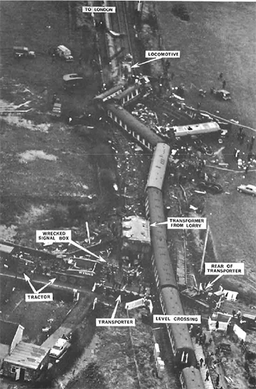

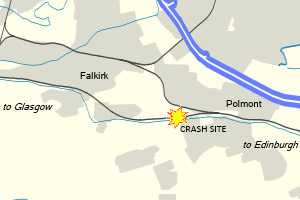

The Polmont rail accident, also known as the Polmont rail disaster, occurred on 30 July 1984 to the west of Polmont, near Falkirk, in Scotland. A westbound push-pull express train travelling from Edinburgh to Glasgow struck a cow which had gained access to the track through a damaged fence from a field near Polmont railway station, causing all six carriages and the locomotive of the train to derail. 13 people were killed and 61 others were injured, 17 of them seriously. The accident led to a debate about the safety of push-pull trains on British Rail.

Lockington railway station was a minor station serving the village of Lockington, East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It was on the Hull to Scarborough Line and was opened on 6 October 1846 by the York and North Midland Railway. It closed on 13 June 1960.

There have been a number of train accidents on the railway network of Victoria, Australia. Some of these are listed below.

The railways of New South Wales, Australia have had many incidents and accidents since their formation in 1831. There are close to 1000 names associated with rail-related deaths in NSW on the walls of the Australian Railway Monument in Werris Creek. Those killed were all employees of various NSW railways. The details below include deaths of employees and the general public.

This article lists significant fatal, injury-only, and other accidents involving railway rolling stock, including crashes, fires and other incidents in the Australian state of South Australia. The first known incident in this list occurred in 1873 in Smithfield, South Australia.

There are around 6,000 level crossings in the United Kingdom, of which about 1,500 are public highway crossings. This number is gradually being reduced as the risk of accidents at level crossings is considered high. The director of the UK Railway Inspectorate commented in 2004 that "the use of level crossings contributes the greatest potential for catastrophic risk on the railways." The creation of new level crossings on the national network is banned, with bridges and tunnels being the more favoured options. The cost of making significant reductions, other than by simply closing the crossings, is substantial; some commentators argue that the money could be better spent. Some 5,000 crossings are user-worked crossings or footpaths with very low usage. The removal of crossings can improve train performance and lower accident rates, as some crossings have low rail speed limits enforced on them to protect road users. In fact, between 1845 and 1933, there was a 4 miles per hour (6.4 km/h) speed limit on level crossings of turnpike roads adjacent to stations for lines whose authorising Act of Parliament had been consolidated in the Railways Clauses Consolidation Act 1845 although this limit was at least sometimes disregarded.

Peter Frank Stott CBE was a British civil engineer. Specialising in prestressed concrete, he designed several bridges in Australia. Stott's work on the Hammersmith flyover brought him to the attention of the London County Council where he was appointed deputy chief engineer. He subsequently became chief engineer and was appointed Director of Highways and Transportation upon the creation of the Greater London Council. He became one of the first joint controllers at the council when the planning department became part of his remit. Stott left the council to become Director-General of the National Water Council. He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1978 and in 1983 became a professor at King's College London. Stott wrote a 1987 report on the use of open level crossings on the rail network that led to a significant change in British Rail policy and served as president of the Institution of Civil Engineers for 1989–90.