Patience is the ability to endure difficult circumstances. Patience may involve perseverance in the face of delay; tolerance of provocation without responding with disrespect or anger; forbearance when under strain, especially when faced with longer-term difficulties; or being able to wait for a long time without getting irritated or bored. Patience is also used to refer to the character trait of being steadfast. Antonyms include impatience, hastiness, and impetuousness.

A virtue is a trait of excellence, including traits that may be moral, social, or intellectual. The cultivation and refinement of virtue is held to be the "good of humanity" and thus is valued as an end purpose of life or a foundational principle of being. In human practical ethics, a virtue is a disposition to choose actions that succeed in showing high moral standards: doing what is said to be right and avoiding what is wrong in a given field of endeavour, even when doing so may be unnecessary from a utilitarian perspective. When someone takes pleasure in doing what is right, even when it is difficult or initially unpleasant, they can establish virtue as a habit. Such a person is said to be virtuous through having cultivated such a disposition. The opposite of virtue is vice, and the vicious person takes pleasure in habitual wrong-doing to their detriment.

The Beatitudes are blessings recounted by Jesus in Matthew 5:3-10 within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew, and four in the Sermon on the Plain in the Gospel of Luke, followed by four woes which mirror the blessings.

Humility is the quality of being humble. Dictionary definitions describe humility as low self-regard and a sense of unworthiness. In a religious context, humility can mean a recognition of self in relation to a deity, and subsequent submission to that deity as a member of that religion. Outside of a religious context, humility is defined as being "unselved"—liberated from consciousness of self—a form of temperance that is neither having pride nor indulging in self-deprecation.

In Christian theology, charity is considered one of the seven virtues and was understood by Thomas Aquinas as "the friendship of man for God", which "unites us to God". He holds it as "the most excellent of the virtues". Aquinas further holds that "the habit of charity extends not only to the love of God, but also to the love of our neighbor".

Righteousness, or rectitude, is the quality or state of being morally correct and justifiable. It can be considered synonymous with "rightness" or being "upright" or to-the-light and visible. It can be found in Indian, Chinese and Abrahamic religions and traditions, among others, as a theological concept. For example, from various perspectives in Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Confucianism, Taoism, Judaism it is considered an attribute that implies that a person's actions are justified, and can have the connotation that the person has been "judged" or "reckoned" as leading a life that is pleasing to God.

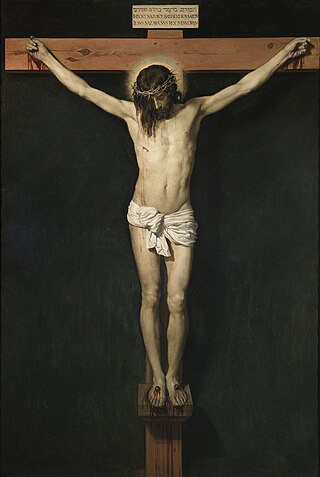

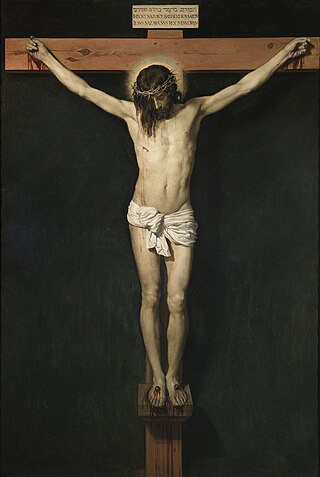

The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas à Kempis, is a Christian devotional book first composed in Medieval Latin as De Imitatione Christi. The devotional text is divided into four books of detailed spiritual instructions: (i) "Helpful Counsels of the Spiritual Life", (ii) "Directives for the Interior Life", (iii) "On Interior Consolation", and (iv) "On the Blessed Sacrament". The devotional approach of The Imitation of Christ emphasises the interior life and withdrawal from the mundanities of the world, as opposed to the active imitation of Christ practised by other friars. The devotions of the books emphasize devotion to the Eucharist as the key element of spiritual life.

Fakir, faqeer, or faqīr, derived from faqr, is an Islamic term traditionally used for Sufi Muslim ascetics who renounce their worldly possessions and dedicate their lives to the worship of God. They do not necessarily renounce all relationships, or take vows of poverty, but the adornments of the temporal worldly life are kept in perspective. The connotations of poverty associated with the term relate to their spiritual neediness, not necessarily their physical neediness.

The Psychomachia is a poem by the Late Antique Latin poet Prudentius, from the early fifth century AD. It has been considered to be the first and most influential "pure" medieval allegory, the first in a long tradition of works as diverse as the Romance of the Rose, Everyman and Piers Plowman; however, a manuscript discovered in 1931 of a speech by the second-century academic skeptic philosopher Favorinus employs psychomachia, suggesting that he may have invented the technique.

The Antichrist is a book by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, originally published in 1895.

Dorotheus of Gaza or Abba Dorotheus, was a Christian monk and abbot.

Walter Arnold Kaufmann was a German-American philosopher, translator, and poet. A prolific author, he wrote extensively on a broad range of subjects, such as authenticity and death, moral philosophy and existentialism, theism and atheism, Christianity and Judaism, as well as philosophy and literature. He served more than 30 years as a professor at Princeton University.

The Fruit of the Holy Spirit is a biblical term that sums up nine attributes of a person or community living in accord with the Holy Spirit, according to chapter 5 of the Epistle to the Galatians: "But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control." The fruit is contrasted with the works of the flesh discussed in the previous verses.

Matthew 5:44, the forty-fourth verse in the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament, also found in Luke 6:27–36, is part of the Sermon on the Mount. This is the second verse of the final antithesis, that on the commandment to "Love thy neighbour as thyself". In the chapter, Jesus refutes the teaching of some that one should "hate [one's] enemies".

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the human self:

Jesus was criticised in the first century CE by the Pharisees and scribes for disobeying Mosaic Law. He was decried in Judaism as a failed Jewish messiah claimant and a false prophet by most Jewish denominations. Judaism also considers the worship of any person a form of idolatry, and rejects the claim that Jesus was divine. Some psychiatrists, religious scholars and writers explain that Jesus' family, followers and contemporaries seriously regarded him as delusional, possessed by demons, or insane.

A Treatise Concerning Religious Affections is a publication written in 1746 by Jonathan Edwards describing his philosophy about the process of Christian conversion in Northampton, Massachusetts, during the First Great Awakening, which emanated from Edwards' congregation starting in 1734.

Maqām refers to each stage a Sufi's soul must attain in its search for God. The stations are derived from the most routine considerations a Sufi must deal with on a day-to-day basis and is essentially an embodiment of both mystical knowledge and Islamic law (Sharia). Although the number and order of maqamat are not universal the majority agree on the following seven: Tawba, Wara', Zuhd, Faqr, Ṣabr, Tawakkul, and Riḍā. Sufis believe that these stations are the grounds of the spiritual life, and they are viewed as a mode through which the most elemental aspects of daily life begin to play a vital role in the overall attainment of oneness with God.

Akrodha literally means "free from anger". It's an important virtue in Indian philosophy and Hindu ethics.

ʿAbd al-Razzāq b. ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī, also known as Abū Bakr al-Jīlī or ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Jīlānī for short, or reverentially as Shaykh ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Jīlānī by Sunni Muslims, was a Persian Sunni Muslim Hanbali theologian, jurist, traditionalist and Sufi mystic based in Baghdad. He received his initial training in the traditional Islamic sciences from his father, Abdul-Qadir Gilani, the founder of the Qadiriyya order of Sunni mysticism, prior to setting out "on his own to attend the lectures of other prominent Hanbali scholars" in his region. He is sometimes given the Arabic honorary epithet Tāj al-Dīn in Sunni tradition, due to his reputation as a mystic of the Hanbali school.