Natural law is a system of law based on a close observation of natural order and human nature, from which values, thought by natural law's proponents to be intrinsic to human nature, can be deduced and applied independently of positive law. According to the theory of law called jusnaturalism, all people have inherent rights, conferred not by act of legislation but by "God, nature, or reason". Natural law theory can also refer to "theories of ethics, theories of politics, theories of civil law, and theories of religious morality".

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, justice, liberty, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of laws by authority: what they are, if they are needed, what makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect, what form it should take, what the law is, and what duties citizens owe to a legitimate government, if any, and when it may be legitimately overthrown, if ever.

Tabula rasa is the idea of individuals being born empty of any built-in mental content, so that all knowledge comes from later perceptions or sensory experiences. Proponents typically form the extreme "nurture" side of the nature versus nurture debate, arguing that humans are born without any "natural" psychological traits and that all aspects of one's personality, social and emotional behaviour, knowledge, or sapience are afterwards imprinted by one's environment onto the mind as one would onto a wax tablet. This idea is the central view posited in the theory of knowledge known as empiricism. Empiricists disagree with the doctrines of innatism or rationalism, which hold that the mind is born already in possession of certain knowledge or rational capacity.

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it is a core concept of constitutionalism, while not necessarily convened and written down in a constituent assembly and constitution.

Reason is the capacity of applying logic consciously by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, science, language, mathematics, and art, and is normally considered to be a distinguishing ability possessed by humans. Reason is sometimes referred to as rationality.

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification", often in contrast to other possible sources of knowledge such as faith, tradition, or sensory experience. More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".

Will, within philosophy, is a faculty of the mind. Will is important as one of the parts of the mind, along with reason and understanding. It is considered central to the field of ethics because of its role in enabling deliberate action.

Teleology or finality is a branch of causality giving the reason or an explanation for something as a function of its end, its purpose, or its goal, as opposed to as a function of its cause. James Wood, in his Nuttall Encyclopaedia, explained the meaning of teleology as "the doctrine of final causes, particularly the argument for the being and character of God from the being and character of His works; that the end reveals His purpose from the beginning, the end being regarded as the thought of God at the beginning, or the universe viewed as the realisation of Him and His eternal purpose."

Human potential is the capacity for humans to improve themselves through studying, training, and practice, to reach the limit of their ability to develop aptitudes and skills. "Inherent within the notion of human potential is the belief that in reaching their full potential an individual will be able to lead a happy and more fulfilled life".

In philosophy, economics, and political science, the common good is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, or alternatively, what is achieved by citizenship, collective action, and active participation in the realm of politics and public service. The concept of the common good differs significantly among philosophical doctrines. Early conceptions of the common good were set out by Ancient Greek philosophers, including Aristotle and Plato. One understanding of the common good rooted in Aristotle's philosophy remains in common usage today, referring to what one contemporary scholar calls the "good proper to, and attainable only by, the community, yet individually shared by its members."

A need is dissatisfaction at a point of time and in a given context. Needs are distinguished from wants. In the case of a need, a deficiency causes a clear adverse outcome: a dysfunction or death. In other words, a need is something required for a safe, stable and healthy life while a want is a desire, wish or aspiration. When needs or wants are backed by purchasing power, they have the potential to become economic demands.

Agency is the capacity of an actor to act in a given environment. It is independent of the moral dimension, which is called moral agency.

Phronesis is a type of wisdom or intelligence concerned with practical action. It implies both good judgment and excellence of character and habits, and was a common topic of discussion in ancient Greek philosophy. Classical works about this topic are still influential today. In Aristotelian ethics, the concept was distinguished from other words for wisdom and intellectual virtues—such as episteme and sophia—because of its practical character. The traditional Latin translation is prudentia, which is the source of the English word "prudence".

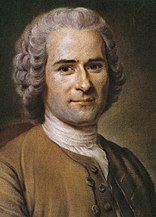

Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, also commonly known as the "Second Discourse", is a 1755 treatise by philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, on the topic of social inequality and its origins. The work was written in 1754 as Rousseau's entry in a competition by the Academy of Dijon, and was published in 1755.

Moral agency is an individual's ability to make moral choices based on some notion of right and wrong and to be held accountable for these actions. A moral agent is "a being who is capable of acting with reference to right and wrong."

Human nature comprises the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of thinking, feeling, and acting—that humans are said to have naturally. The term is often used to denote the essence of humankind, or what it 'means' to be human. This usage has proven to be controversial in that there is dispute as to whether or not such an essence actually exists.

Common sense is "knowledge, judgement, and taste which is more or less universal and which is held more or less without reflection or argument". As such, it is often considered to represent the basic level of sound practical judgement or knowledge of basic facts that any adult human being ought to possess. It is "common" in the sense of being shared by nearly all people. The everyday understanding of common sense is ultimately derived from historical philosophical discussions. Relevant terms from other languages used in such discussions include Latin sensus communis, Ancient Greek κοινὴ αἴσθησις, and French bon sens. However, these are not straightforward translations in all contexts, and in English different shades of meaning have developed. In philosophical and scientific contexts, since the Age of Enlightenment the term "common sense" has been used for rhetorical effect both approvingly and disapprovingly. On the one hand it has been a standard for good taste, good sense, and source of scientific and logical axioms. On the other hand it has been equated to conventional wisdom, vulgar prejudice, and superstition.

Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity is a work of philosophy by Charles Taylor, published in 1989 by Harvard University Press. It is an attempt to articulate and to write a history of the "modern identity".

The philosophy of human rights attempts to examine the underlying basis of the concept of human rights and critically looks at its content and justification. Several theoretical approaches have been advanced to explain how and why the concept of human rights developed.

Epistemic democracy refers to a range of views in political science and philosophy which see the value of democracy as based, at least in part, on its ability to make good or correct decisions. Epistemic democrats believe that the legitimacy or justification of democratic government should not be exclusively based on the intrinsic value of its procedures and how they embody or express values such as fairness, equality, or freedom. Instead, they claim that a political system based on political equality can be expected to make good political decisions, and possibly decisions better than any alternative form of government .