Description

Dentition

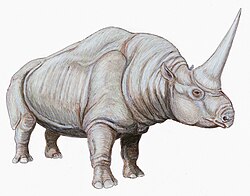

Though generally similar to other genera within the subfamily, Megahippus is unique in the presence of a well defined ridge across the inner edge of the premolars 1-3 along with the presence of large, frontward-facing lower incisors. [2] Unlike the incisors of other anchitheriines like Hypohippus , they would have been large and high-crowned. Between the two species, there is evidence of a trend of their premolars shrinking over time, with them being larger proportionally in M. mckennai. [3] Both Megahippus and Hypohippus show a general trend in the increase in frequency of conchets in their upper cheek teeth potentially due to the segregation of the section when compared to the earlier Anchitherium . [4]

Crania

Megahippus is generally comparable with other genera in the subfamily, having a short premaxilla that constricts before the first premolar. The infra-orbital fossa is located about the P4 with the facial fossa positioned above and behind the infra-orbital fossa. The placement of the facial fossa more similar to the more basal Archaeohippus than the closely related Hypohippus. [3]

Postcrania

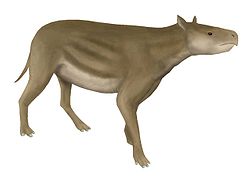

The limb morphology of Megahippus is similar to those seen in living equines, having adaptations towards the restricted movement of the fetlock. Thought this seems to be a convergent adaption related to the support of larger body masses. The ungual of larger anchitheriins like Megahippus was also similar to Equus which would have given the animal a more rounded phalanx then smaller smaller genera. [5] [6] Unlike modern horses, the feet of Megahippus and other anchitheriins were tridactyl. [7] The estimated body masses of the species of the genus are 194.9 kg (430 lb) for M. mckennai and 266.2 kg (587 lb) for M. matthewi. [8]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.