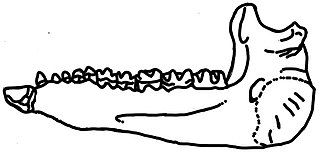

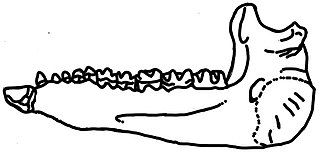

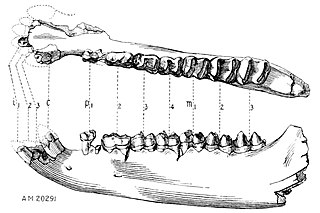

Andrewsarchus, meaning "Andrews' ruler", is an extinct genus of artiodactyl that lived during the Middle Eocene in what is now China. The genus was first described by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1924 with the type species A. mongoliensis based on a largely complete cranium. A second species, A. crassum, was described in 1977 based on teeth. A mandible, formerly described as Paratriisodon, does probably belong to Andrewsarchus as well. The genus has been historically placed in the families Mesonychidae or Arctocyonidae, or was considered to be a close relative of whales. It is now regarded as the sole member of its own family, Andrewsarchidae, and may have been related to entelodonts. Fossils of Andrewsarchus have been recovered from the Middle Eocene Irdin Manha, Lushi, and Dongjun Formations of Inner Mongolia, each dated to the Irdinmanhan Asian land mammal age.

Paraceratherium is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch. The first fossils were discovered in what is now Pakistan, and remains have been found across Eurasia between China and the Balkans. Paraceratherium means "near the hornless beast", in reference to Aceratherium, the genus in which the type species P. bugtiense was originally placed.

Paraceratheriidae is an extinct family of long-limbed, hornless rhinocerotoids, native to Asia and Eastern Europe that originated in the Eocene epoch and lived until the end of the Oligocene. They represent some of the largest terrestrial mammals to have ever lived.

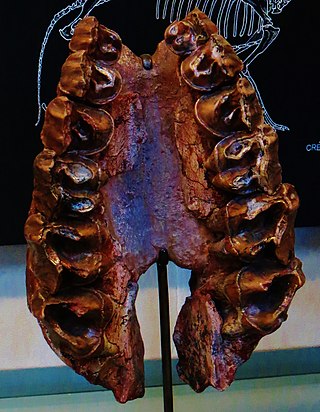

Sinotherium is an extinct genus of single-horned elasmotheriine rhinocerotids that lived from the late Miocene to Early Pliocene. It was ancestral to Elasmotherium, demonstrating a very important evolutionary transition from nasal-horned elasmotheriines to frontal-horned elasmotheriines. Its fossils have been found in the Karabulak Formation of Kazakhstan, lower jaw and teeth have been found in Mongolia, and a partial skull is known from the upper part of the Liushu Formation of western China. Sinotherium diverged from the ancestral genus, Iranotherium, first found in Iran, during the early Pliocene. Some experts prefer to lump Sinotherium, and Iranotherium into Elasmotherium.

Amynodontidae is a family of extinct perissodactyls related to true rhinoceroses. They are commonly portrayed as semiaquatic hippo-like rhinos but this description only fits members of the Metamynodontini; other groups of amynodonts like the cadurcodontines had more typical ungulate proportions and convergently evolved a tapir-like proboscis.

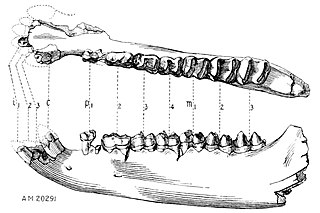

Brachyhyops is an extinct genus of entelodont artiodactyl mammal that lived during the Eocene Epoch of western North America and southeastern Asia. The first fossil remains of Brachyhyops are recorded from the late Eocene deposits of Beaver Divide in central Wyoming and discovered by paleontology crews from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History during the early 20th century. The type species, Brachyhyops wyomingensis, is based on a single skull and was named by E.H. Colbert in 1937, but was not officially described until 1938. During the latter half of the 20th century, additional specimens from North America have been recorded from Saskatchewan and as far south as Texas, indicating that Brachyhyops had a broad distribution and was well-dispersed throughout western North America.

Asiatosuchus is an extinct genus of crocodyloid crocodilians that lived in Eurasia during the Paleogene. Many Paleogene crocodilians from Europe and Asia have been attributed to Asiatosuchus since the genus was named in 1940. These species have a generalized crocodilian morphology typified by flat, triangular skulls. The feature that traditionally united these species under the genus Asiatosuchus is a broad connection or symphysis between the two halves of the lower jaw. Recent studies of the evolutionary relationships of early crocodilians along with closer examinations of the morphology of fossil specimens suggest that only the first named species of Asiatosuchus, A. grangeri from the Eocene of Mongolia, belongs in the genus. Most species are now regarded as nomina dubia or "dubious names", meaning that their type specimens lack the unique anatomical features necessary to justify their classification as distinct species. Other species such as "A." germanicus and "A." depressifrons are still considered valid species, but they do not form an evolutionary grouping with A. grangeri that would warrant them being placed together in the genus Asiatosuchus.

The Irdin Manha Formation is a geological formation from the Eocene located in Inner Mongolia, China, a few kilometres south of the Mongolian border.

Brontotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the order Perissodactyla, the order that includes horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Superficially, they looked rather like rhinos with some developing bony nose horns, and were some of the earliest mammals to have evolved large body sizes of several tonnes. They lived around 56–34 million years ago, until the very close of the Eocene. Brontotheres had a Holarctic distribution, with the exception of Western Europe: they occupied North America, Asia, and Eastern Europe. They were the first fossilized mammals to be discovered west of the Mississippi, and were first discovered in South Dakota.

Homogalax is an extinct genus of tapir-like odd-toed ungulate. It was described on the basis of several fossil finds from the northwest of the United States, whereby the majority of the remains come from the state of Wyoming. The finds date to the Lower Eocene between 56 and 48 million years ago. In general, Homogalax was very small, only reaching the weight of today's peccaries, with a maximum of 15 kg. Phylogenetic analysis suggests the genus to be a basal member of the clade that includes today's rhinoceros and tapirs. In contrast to these, Homogalax was adapted to fast locomotion.

Eggysodontidae is a family of perissodactyls, closely related to rhinoceroses. Fossils have been found in Oligocene deposits in Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, China, and Mongolia.

Urtinotherium is an extinct genus of paracerathere mammals. It was a large animal that was closely related to Paraceratherium, and found in rocks dating from the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene period. The remains were first discovered in the Urtyn Obo region in Inner Mongolia, which the name Urtinotherium is based upon. Other referred specimens are from northern China.

The San Jose Formation is an Early Eocene geologic formation in the San Juan Basin of New Mexico and Colorado.

Forstercooperia is an extinct genus of forstercooperiine paraceratheriid rhinocerotoids from the Middle Eocene of Asia.

Astorgosuchus is an extinct monospecific genus of crocodilian, closely related to true crocodiles, that lived in Pakistan during the late Oligocene period. This crocodile may have reached lengths of up to 7–8 m (23–26 ft) and is known to have preyed on many of the large mammals found in its environment. Bite marks of a large crocodile have been found on the bones of juvenile Paraceratherium, however if these were left by Astorgosuchus cannot be said with certainty. The genus contains a single species, Astorgosuchus bugtiensis, which was originally named as a species of Crocodylus in 1908 and was moved to its own genus in 2019.

Deperetella is an extinct genus of deperetellid perissodactyls from Middle to Late Eocene of Asia. The genus was defined in 1925 by W. D. Matthew and Walter W. Granger, who named it after French paleontologist Charles Depéret. The type species is Deperetella cristata.

Ronzotherium is an extinct genus of perissodactyl mammal from the family Rhinocerotidae. The name derives from the hill of 'Ronzon', the French locality near Le Puy-en-Velay at which it was first discovered, and the Greek suffix 'therium' meaning 'beast'. At present 5 species have been identified from several localities in Europe and Asia, spanning the Late Eocene to Upper Oligocene.

Allacerops is an extinct genus of odd-toed ungulate belong to the rhinoceros-like family Eggysodontidae. It was a small, ground-dwelling browser, and fossils have been found in Oligocene deposits throughout Central and East Asia.

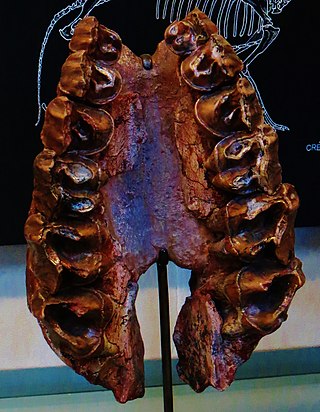

Dzungariotherium is a genus of paraceratheriid, an extinct group of large, hornless rhinocerotoids, which lived during the middle and late Oligocene of northwest China. The type species D. orgosense was described in 1973 based on fossils—mainly teeth—from Dzungaria in Xinjiang, northwest China.

Uintaceras is an extinct genus of medium-sized early rhinocerotoids that lived in North America during the Middle Eocene, with only the type species U. radinskyi, named in 1997, currently contained within the genus. Traditionally considered the oldest and most primitive species of the Rhinocerotidae, it may instead have been a close relative of the Asian Paraceratheriidae. The dubious species Forstercooperia (Hyrachyus) grandis is also possibly the same animal as Uintaceras, although the Asian material of F. grandis was assignable to Forstercooperia confluens.