Perissodactyla is an order of ungulates. The order includes about 17 living species divided into three families: Equidae, Rhinocerotidae (rhinoceroses), and Tapiridae (tapirs). They typically have reduced the weight-bearing toes to three or one of the five original toes, though tapirs retain four toes on their front feet. The nonweight-bearing toes are either present, absent, vestigial, or positioned posteriorly. By contrast, artiodactyls bear most of their weight equally on four or two of the five toes: their third and fourth toes. Another difference between the two is that perissodactyls digest plant cellulose in their intestines, rather than in one or more stomach chambers as artiodactyls, with the exception of Suina, do.

Ungulates are members of the diverse clade Euungulata, which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to be a polyphyletic and thereby invalid clade based on molecular data. As a result, true ungulates had since been reclassified to the newer clade Euungulata in 2001 within the clade Laurasiatheria while Paenungulata has been reclassified to a distant clade Afrotheria. Living ungulates are divided into two orders: Perissodactyla including equines, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and Artiodactyla including cattle, antelope, pigs, giraffes, camels, sheep, deer, and hippopotamuses, among others. Cetaceans such as whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also classified as artiodactyls, although they do not have hooves. Most terrestrial ungulates use the hoofed tips of their toes to support their body weight while standing or moving. Two other orders of ungulates, Notoungulata and Litopterna, both native to South America, became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, around 12,000 years ago.

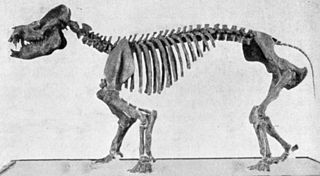

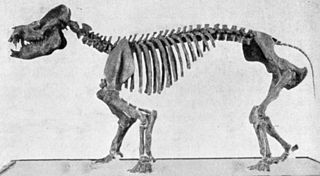

Teleoceras is an extinct genus of rhinocerotid. It lived in North America during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs during the Hemingfordian to the end of Hemphillian from around 17.5 to 4.9 million years ago. It grew up to lengths of 13 feet long.

Entelodontidae is an extinct family of pig-like artiodactyls which inhabited the Northern Hemisphere from the late Eocene to the early Miocene epochs, about 38-19 million years ago. Their large heads, low snouts, narrow gait, and proposed omnivorous diet inspires comparisons to suids and tayassuids (peccaries), and historically they have been considered closely related to these families purely on a morphological basis. However, studies which combine morphological and molecular (genetic) data on artiodactyls instead suggest that entelodonts are cetancodontamorphs, more closely related to hippos and cetaceans through their resemblance to Pakicetus, than to basal pigs like Kubanochoerus and other ungulates.

Paraceratherium is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch. The first fossils were discovered in what is now Pakistan, and remains have been found across Eurasia between China and the Balkans. Paraceratherium means "near the hornless beast", in reference to Aceratherium, the genus in which the type species P. bugtiense was originally placed.

Chalicotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous, odd-toed ungulate (perissodactyl) mammals that lived in North America, Eurasia, and Africa from the Middle Eocene to the Early Pleistocene. They are often called chalicotheres, a term which is also applied to the broader grouping of Chalicotherioidea. They are noted for their unusual morphology compared to other ungulates, such as their clawed forelimbs. Members of the subfamily Chalicotheriinae developed elongate gorilla-like forelimbs that are thought to have been used to grasp vegetation. They are thought to have been browsers on foliage as well as possibly bark and fruit.

Chalicotherium is a genus of extinct odd-toed ungulates of the order Perissodactyla and family Chalicotheriidae. The genus is known from Europe and Asia, from the Middle Miocene to Late Miocene.

Coryphodon is an extinct genus of pantodonts of the family Coryphodontidae.

Daphoenus is an extinct genus of amphicyonids. Daphoenus inhabited North America from the Late Eocene to the Middle Miocene, 37.2—16.0 Mya, existing for approximately 21 million years.

Amynodontidae is a family of extinct perissodactyls related to true rhinoceroses. They are commonly portrayed as semiaquatic hippo-like rhinos but this description only fits members of the Metamynodontini; other groups of amynodonts like the cadurcodontines had more typical ungulate proportions and convergently evolved a tapir-like proboscis.

Leptomeryx is an extinct genus of ruminant of the family Leptomerycidae, endemic to North America during the Eocene through Oligocene 38–24.8 Mya, existing for approximately 13.2 million years. It was a small deer-like ruminant with somewhat slender body.

Leptomerycinae is an extinct subfamily within the ruminant family Leptomerycidae. It contains three genera, Leptomeryx, Pronodens, Pseudoparablastomeryx, and Santuccimeryx, which lived in North America during the Middle Eocene to Middle Miocene. Leptomeryx may also have occurred in Asia during the Early Oligocene. Leptomerycines were primitive and ancient ruminants, resembling small deer or musk deer, although they were more closely related to modern chevrotains.

Brontotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the order Perissodactyla, the order that includes horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Superficially, they looked rather like rhinos with some developing bony nose horns, and were some of the earliest mammals to have evolved large body sizes of several tonnes. They lived around 56–34 million years ago, until the very close of the Eocene. Brontotheres had a Holarctic distribution, with the exception of Western Europe: they occupied North America, Asia, and Eastern Europe. They were the first fossilized mammals to be discovered west of the Mississippi, and were first discovered in South Dakota.

Paleontology in Nebraska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nebraska. Nebraska is world-famous as a source of fossils. During the early Paleozoic, Nebraska was covered by a shallow sea that was probably home to creatures like brachiopods, corals, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous, a swampy system of river deltas expanded westward across the state. During the Permian period, the state continued to be mostly dry land. The Triassic and Jurassic are missing from the local rock record, but evidence suggests that during the Cretaceous the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, where ammonites, fish, sea turtles, and plesiosaurs swam. The coasts of this sea were home to flowers and dinosaurs. During the early Cenozoic, the sea withdrew and the state was home to mammals like camels and rhinoceros. Ice Age Nebraska was subject to glacial activity and home to creatures like the giant bear Arctodus, horses, mammoths, mastodon, shovel-tusked proboscideans, and Saber-toothed cats. Local Native Americans devised mythical explanations for fossils like attributing them to water monsters killed by their enemies, the thunderbirds. After formally trained scientists began investigating local fossils, major finds like the Agate Springs mammal bone beds occurred. The Pleistocene mammoths Mammuthus primigenius, Mammuthus columbi, and Mammuthus imperator are the Nebraska state fossils.

Paleontology in the United States refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the United States. Paleontologists have found that at the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas. Later the seas were largely replaced by swamps, home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

Radinskya is an extinct perissodactyl-like mammal from the Paleocene of China. It is named after palaeontologist and perissodactyl expert Leonard Radinsky who died prematurely in 1985.

Altungulata or Pantomesaxonia is an invalid clade (mirorder) of ungulate mammals comprising the perissodactyls, hyracoids, and tethytheres.

Urtinotherium is an extinct genus of paracerathere mammals. It was a large animal that was closely related to Paraceratherium, and found in rocks dating from the Late Eocene to Early Oligocene period. The remains were first discovered in the Urtyn Obo region in Inner Mongolia, which the name Urtinotherium is based upon. Other referred specimens are from northern China.

Forstercooperia is an extinct genus of forstercooperiine paraceratheriid rhinocerotoids from the Middle Eocene of Asia.

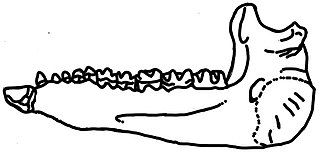

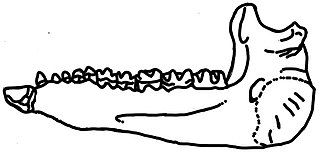

Cadurcodon is an extinct genus of amynodont that lived during the Late Eocene to the Oligocene period. Fossils have been found throughout Mongolia and China. It may have sported a tapir-like proboscis due to the distinct features found in fossil skulls.