| Palaeotherium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Palaeotherium magnum cast skeleton from the French commune of Mormoiron, National Museum of Natural History, France | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | † Palaeotheriidae |

| Subfamily: | † Palaeotheriinae |

| Genus: | † Palaeotherium Cuvier, 1804 |

| Type species | |

| †Palaeotherium magnum Cuvier, 1804 | |

| Other species | |

For subspecies suggested, see below. | |

| Synonyms | |

Genus synonymy

Synonyms of P. magnum

Synonyms of P. medium

Synonyms of P. crassum

Synonyms of P. curtum

Synonyms of P. duvali

Synonyms of P. castrense

Synonyms of P. siderolithicum

Synonyms of P. eocaenum

Synonyms of P. muehlbergi

Dubious species

| |

Palaeotherium is an extinct genus of equoid that lived in Europe and possibly the Middle East from the Middle Eocene to the Early Oligocene. It is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, a group exclusive to the Palaeogene that was closest in relation to the Equidae, which contains horses plus their closest relatives and ancestors. Fossils of Palaeotherium were first described in 1782 by the French naturalist Robert de Lamanon and then closely studied by another French naturalist, Georges Cuvier, after 1798. Cuvier erected the genus in 1804 and recognized multiple species based on overall fossil sizes and forms. As one of the first fossil genera to be recognized with official taxonomic authority, it is recognized as an important milestone within the field of palaeontology. The research by early naturalists on Palaeotherium contributed to the developing ideas of evolution, extinction, and succession and demonstrating the morphological diversity of different species within one genus.

Contents

- Taxonomy

- Research history

- Classification and evolution

- Inner systematics

- Description

- Skull

- Dentition

- Postcranial skeleton

- Size

- Footprints

- Palaeobiology

- Palaeoecology

- Middle Eocene

- Late Eocene

- Extinction

- Notes

- References

- External links

Since Cuvier's descriptions, many other naturalists from Europe and the Americas recognized many species of Palaeotherium, some valid, some reclassified to different genera afterward, and others being eventually rendered invalid. The German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen modernized its taxonomy due to his recognition of many subspecies as part of his dissertation in 1968, which were subsequently accepted by other palaeontologists. Today, there are sixteen known species recognized, many of which have multiple subspecies. In 1992, the French palaeontologist Jean-Albert Remy recognized two subgenera that most species are classified to based on cranial anatomies: the specialized Palaeotherium and the more generalized Franzenitherium.

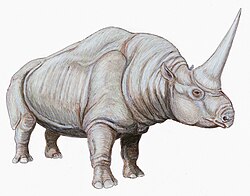

Palaeotherium is an evolutionarily derived member of its family with tridactyl (or three-toed) forelimbs and hindlimbs, small post-canine diastemata (gaps between teeth), and premolars that are usually developed into molar-like forms. It shares many similar anatomical traits with other perissodactyls and has a large diversity in anatomical traits by species, with some species like P. magnum, P. curtum, and P. crassum being stockier in build and P. medium being more cursorial (or adapted for running). The genus ranges in size from the small species P. lautricense, with an estimated weight of 36 kg (79 lb), to the massive P. giganteum, thought to have been capable of weighing over 700 kg (1,500 lb). P. magnum, known by two mostly complete skeletons from France, could have reached approximately 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) in shoulder height and 2.52 m (8 ft 3 in) in length. The large-sized species were therefore amongst the largest mammals in the Eocene of Europe. Palaeotherium may have lived in herds and, as demonstrated by its dentition, was able to actively niche partition with another palaeothere Plagiolophus by specializing on softer leaves and fruit, although both were mostly leaf-eating.

Palaeotherium and other genera of the subfamily Palaeotheriinae likely descended from the earlier subfamily Pachynolophinae, which lived in both Europe and Asia as opposed to North America unlike undisputed members of the Equidae. By the time that the first species P. eocaenum appeared in the middle Eocene, western Europe was an archipelago that was isolated from the rest of Eurasia, meaning that it and subsequent species lived in an environment with various other faunas that also evolved with strong levels of endemism. The Iberian Peninsula had its own level of endemism with several species that are only known within the region, although they were replaced by more widespread species from central Europe by the late Eocene. Within both the middle and late Eocene, Palaeotherium consistently maintained a high species diversity and endured major environmental changes leading to a faunal turnover that occurred by the beginning of the late Eocene.

By the early Oligocene, most of its species went extinct along with many genera of western European mammals as part of the Grande Coupure extinction and faunal turnover event, the causes of the extinctions being attributed mainly to environmental changes from increased glaciation and seasonality, negative interactions with immigrant faunas from Asia (competition and/or predation), or some combination of the two. P. medium survived past the Grande Coupure probably due to its cursorial nature that allowed it to travel across open lands more efficiently and escape immigrant carnivores; it was the last species of its genus and went extinct not long after the faunal turnover event.