The Baltic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively or as a second language by a population of about 6.5–7.0 million people mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Europe. Together with the Slavic languages, they form the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European family.

Finno-Ugric is a traditional linguistic grouping of all languages in the Uralic language family except for the Samoyedic languages. Its once commonly accepted status as a subfamily of Uralic is based on criteria formulated in the 19th century and is criticized by some contemporary linguists such as Tapani Salminen and Ante Aikio. The three most spoken Uralic languages, Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian, are all included in Finno-Ugric.

The Uralic languages, sometimes called the Uralian languages, form a language family of 42 languages spoken predominantly in Europe and North Asia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian. Other languages with speakers above 100,000 are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi spoken in the European parts of the Russian Federation. Still smaller minority languages are Sámi languages of the northern Fennoscandia; other members of the Finnic languages, ranging from Livonian in northern Latvia to Karelian in northwesternmost Russia; and the Samoyedic languages, Mansi and Khanty spoken in Western Siberia.

In historical linguistics, the homeland or Urheimat of a proto-language is the region in which it was spoken before splitting into different daughter languages. A proto-language is the reconstructed or historically-attested parent language of a group of languages that are genetically related.

The European Neolithic is the period from the arrival of Neolithic technology and the associated population of Early European Farmers in Europe, c. 7000 BC until c. 2000–1700 BC. The Neolithic overlaps the Mesolithic and Bronze Age periods in Europe as cultural changes moved from the southeast to northwest at about 1 km/year – this is called the Neolithic Expansion.

Old Europe is a term coined by the Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas to describe what she perceived as a relatively homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic and Copper Age culture or civilisation in Southeast Europe, centred in the Lower Danube Valley. Old Europe is also referred to in some literature as the Danube civilisation.

The Germanic substrate hypothesis attempts to explain the purportedly distinctive nature of the Germanic languages within the context of the Indo-European languages. Based on the elements of Common Germanic vocabulary and syntax which do not seem to have cognates in other Indo-European languages, it claims that Proto-Germanic may have been either a creole or a contact language that subsumed a non-Indo-European substrate language, or a hybrid of two quite different Indo-European languages, mixing the centum and satem types. Which culture or cultures may have contributed the substrate material is an ongoing subject of academic debate and study.

The Paleo-Balkan languages are a geographical grouping of various Indo-European languages that were spoken in the Balkans and surrounding areas in ancient times. In antiquity, Dacian, Greek, Illyrian, Messapic, Paeonian, Phrygian and Thracian were the Paleo-Balkan languages which were attested in literature. They may have included other unattested languages.

Proto-Uralic is the unattested reconstructed language ancestral to the modern Uralic language family. The reconstructed language is thought to have been originally spoken in a small area in about 7000–2000 BCE, and then expanded across northern Eurasia, gradually diverging into a dialect continuum and then a language family in the process. The location of the area or Urheimat is not known, and various strongly differing proposals have been advocated, but the vicinity of the Ural Mountains is generally accepted as the most likely.

The Finnic or Baltic Finnic languages constitute a branch of the Uralic language family spoken around the Baltic Sea by the Baltic Finnic peoples. There are around 7 million speakers, who live mainly in Finland and Estonia.

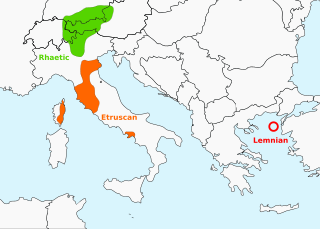

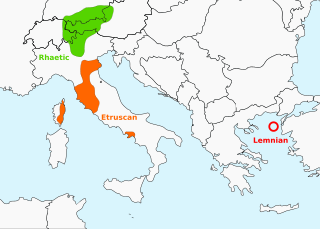

Tyrsenian, named after the Tyrrhenians is a proposed extinct family of closely related ancient languages put forward by linguist Helmut Rix in 1998, which consists of the Etruscan language of northern, central and south-western Italy, and eastern Corsica (France); the Raetic language of the Alps, named after the Rhaetian people; and the Lemnian language of the Aegean Sea. Camunic in northern Lombardy, between Etruscan and Raetic, may belong to the family as well, but evidence of such is limited. The Tyrsenian languages are generally considered Pre-Indo-European and Paleo-European.

The Trojan language was the language spoken in Troy during the Late Bronze Age. The identity of the language is unknown, and it is not certain that there was one single language used in the city at the time.

Kaino Kalevi Wiik was a professor of phonetics at the University of Turku, Finland. He was best known for his controversial hypothesis about the effect of the Uralic contact influence on the creation of various Indo-European protolanguages in Northern Europe such as Germanic, Slavic, and Baltic. He also based much of his hypothetical structures on results of genetics of his time. Ludomir R. Lozny states, "Wiik's controversial ideas are rejected by the majority of the scholarly community, but they have attracted the enormous interest of a wider audience."

The Proto-Indo-European homeland was the prehistoric linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). From this region, its speakers migrated east and west, and went on to form the proto-communities of the different branches of the Indo-European language family.

The pre-Indo-European languages are any of several ancient languages, not necessarily related to one another, that existed in Prehistoric Europe, Asia Minor, Ancient Iran and Southern Asia before the arrival of speakers of Indo-European languages. The oldest Indo-European language texts are Hittite and date from the 19th century BC in Kültepe, and while estimates vary widely, the spoken Indo-European languages are believed to have developed at the latest by the 3rd millennium BC. Thus, the pre-Indo-European languages must have developed earlier than or, in some cases, alongside the Indo-European languages that ultimately displaced almost all of them.

Paleo-Sardinian, also known as Proto-Sardinian or Nuragic, is an extinct language, or perhaps set of languages, spoken on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia by the ancient Sardinian population during the Nuragic era. Starting from the Roman conquest with the establishment of a specific province, a process of language shift took place, wherein Latin came slowly to be the only language spoken by the islanders. Paleo-Sardinian is thought to have left traces in the island's onomastics as well as toponyms, which appear to preserve grammatical suffixes, and a number of words in the modern Sardinian language.

The Proto-Uralic homeland is the earliest location in which the Proto-Uralic language was spoken, before its speakers dispersed geographically causing it to diverge into multiple languages. Various locations have been proposed and debated, although as of 2022 "scholarly consensus now gravitates towards a relatively recent provenance of the Uralic languages east of the Ural mountains".

Proto-Sámi is the hypothetical, reconstructed common ancestor of the Sámi languages. It is a descendant of the Proto-Uralic language.

Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate refers to substratum loanwords from unidentified non-Indo-European and non-Uralic languages that are found in various Finno-Ugric languages, most notably Sami. The presence of Pre-Finno-Ugric substrate in Sami languages was demonstrated by Ante Aikio. Janne Saarikivi points out that similar substrate words are present in Finnic languages as well, but in much smaller numbers.

Paleo-Laplandic is a hypothetical group of extinct but related languages spoken in Sápmi. The speakers of Paleo-Laplandic languages switched to Sámi languages, and the languages became extinct around AD 500. A considerable amount of words in Sámi languages originate from Paleo-Laplandic; more than 1,000 loanwords from Paleo-Laplandic likely exist. Many toponyms in Sápmi originate from Paleo-Laplandic. Because Sámi language etymologies for reindeers have preserved a large number of words from Paleo-Laplandic, this suggests that Paleo-Laplandic groups influenced Sámi culture.