Related Research Articles

In Greek mythology, Achilles or Achilleus was a hero of the Trojan War, the greatest of all the Greek warriors, and the central character of Homer's Iliad. He was the son of the Nereid Thetis and Peleus, king of Phthia.

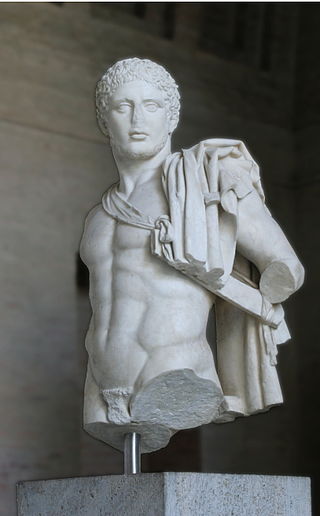

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas was a Trojan hero, the son of the Dardanian prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite. His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy, making Aeneas a second cousin to Priam's children. He is a minor character in Greek mythology and is mentioned in Homer's Iliad. Aeneas receives full treatment in Roman mythology, most extensively in Virgil's Aeneid, where he is cast as an ancestor of Romulus and Remus. He became the first true hero of Rome. Snorri Sturluson identifies him with the Norse god Vidarr of the Æsir.

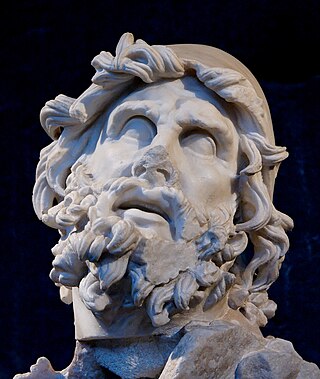

In Greek mythology Odysseus, also known by the Latin variant Ulysses, is a legendary Greek king of Ithaca and the hero of Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. Odysseus also plays a key role in Homer's Iliad and other works in that same epic cycle.

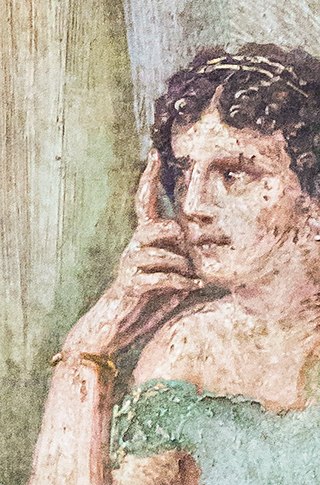

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology, and it has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably Homer's Iliad. The core of the Iliad describes a period of four days and two nights in the tenth year of the decade-long siege of Troy; the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the war's heroes. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid.

The Aeneid is a Latin epic poem that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. Written by the Roman poet Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, the Aeneid comprises 9,896 lines in dactylic hexameter. The first six of the poem's twelve books tell the story of Aeneas' wanderings from Troy to Italy, and the poem's second half tells of the Trojans' ultimately victorious war upon the Latins, under whose name Aeneas and his Trojan followers are destined to be subsumed.

Thetis is a figure from Greek mythology with varying mythological roles. She mainly appears as a sea nymph, a goddess of water, and one of the 50 Nereids, daughters of the ancient sea god Nereus.

Diomedes or Diomede is a hero in Greek mythology, known for his participation in the Trojan War.

Turnus was the legendary King of the Rutuli in Roman history, and the chief antagonist of the hero Aeneas in Virgil's Aeneid.

The word ekphrasis, or ecphrasis, comes from the Greek for the written description of a work of art produced as a rhetorical or literary exercise, often used in the adjectival form ekphrastic. It is a vivid, often dramatic, verbal description of a visual work of art, either real or imagined. Thus, "an ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art." In ancient times, it might refer more broadly to a description of any thing, person, or experience. The word comes from the Greek ἐκ ek and φράσις phrásis, 'out' and 'speak' respectively, and the verb ἐκφράζειν ekphrázein, 'to proclaim or call an inanimate object by name'.

An aristeia or aristia is a scene in the dramatic conventions of epic poetry as in the Iliad, where a hero in battle has his finest moments. Aristeia may result in the death of the hero, and therefore suggests a "battle in which he reaches his peak as a fighter and hero".

A katabasis or catabasis is a journey to the underworld. Its original sense is usually associated with Greek mythology and Classical mythology more broadly, where the protagonist visits the Greek underworld, also known as Hades. The term is also used in a broad sense of any journey to the realm of the dead in other mythological and religious traditions. A katabasis is similar to a nekyia or necromancy, where someone experiences a vision of the underworld or its inhabitants; a nekyia does not generally involve a physical visit, however. One of the most famous examples is that of Odysseus, who performs something on the border of a nekyia and a katabasis in book 11 of The Odyssey; he visits the border of the realms before calling the dead to him using a blood ritual, with it being disputed whether he was at the highest realm of the underworld or the lowest edge of the living world where he performed this.

In Greek mythology, Thoas ,") a king of Aetolia, was the son of Andraemon and Gorge, and one of the heroes who fought for the Greeks in the Trojan War. Thoas had a son Haemon, and an unnamed daughter.

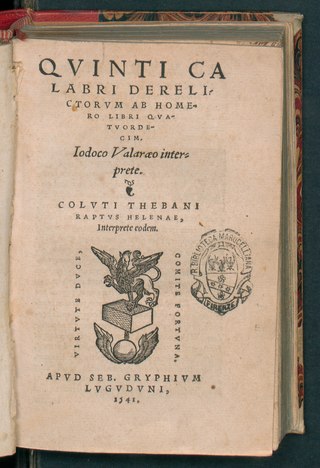

The Posthomerica is an epic poem in Greek hexameter verse by Quintus of Smyrna. Probably written in the 3rd century AD, it tells the story of the Trojan War, between the death of Hector and the fall of Ilium. The poem is an abridgement of the epic poems Aethiopis and Iliou Persis by Arctinus of Miletus and the Little Iliad by Lesches, all now-lost poems of the Epic Cycle.

The shield of Achilles is the shield that Achilles uses in his fight with Hector, famously described in a passage in Book 18, lines 478–608 of Homer's Iliad. The intricately detailed imagery on the shield has inspired many different interpretations of its significance.

The Iliad is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the Odyssey, the poem is divided into 24 books and was written in dactylic hexameter. It contains 15,693 lines in its most widely accepted version. Set towards the end of the Trojan War, a ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Mycenaean Greek states, the poem depicts significant events in the siege's final weeks. In particular, it depicts a fierce quarrel between King Agamemnon and a celebrated warrior, Achilles. It is a central part of the Epic Cycle. The Iliad is often regarded as the first substantial piece of European literature.

In epic poetry, athletics are used as a literary tools to accentuate the themes of the epic, to advance the plot of the epic, and to provide a general historical context to the epic. Epic poetry emphasizes the cultural values and traditions of the time in long narratives about heroes and gods. The word "athletic" is derived from the Greek word athlos, which means a contest for a prize. Athletics appear in some of the most famous examples of Greek and Roman epic poetry including Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, and Virgil's Aeneid.

In Greek mythology, Thersilochus may refer to three different figures:

Eneide is a seven-episode 1971–1972 Italian television drama, adapted by Franco Rossi from Virgil's epic poem the Aeneid. It stars Giulio Brogi as Aeneas and Olga Karlatos as Dido, and also stars Alessandro Haber, Andrea Giordana and Marilù Tolo. RAI originally broadcast the hour-long episodes from 19 December 1971 to 30 January 1972. A shorter theatrical version was released in 1974 as Le avventure di Enea.

In Greek mythology, Halius may refer to the following characters:

References

- 1 2 "Literary Predecessors of the Aeneid". www.cliffsnotes.com. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ↑ Williamson, Makyra (2019). "Vergil's Aeneid: The Cornerstone of Roman Identity". Tenor of Our Times. 8– via ScholarWorks.

- ↑ Virgil (2008). Aeneid. Translated by Ahl. ISBN 978-0199231959.

- 1 2 van Nortwick, Thomas (1980). "Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014)". The Johns Hopkins University Press. 110: 303–314 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 Homer (2011). Iliad of Homer. Translated by Lattimore. ISBN 978-0226470498.

- 1 2 3 Homer (2007). Odyssey of Homer. Translated by Lattimore. ISBN 978-0061244186.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Virgil (2008). Aeneid. Translated by Ahl. ISBN 978-0199231959.

- ↑ Kotin, Joshua (Fall 2001). "Shields of Contradiction and Direction: Ekphrasis in the Iliad and the Aeneid" (PDF). Hirundo: The McGill Journal of Classical Studies, Volume I: 11–16.

- ↑ Capco, Constantine. "Compare and Contrast Odyssey and Aeneas". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ↑ Gross, Nicolas P. (2003). "Mantles Woven with Gold: Pallas' Shroud and the End of the "Aeneid"". The Classical Journal. 99 (2): 135–156. ISSN 0009-8353.