Psychotherapy is the use of psychological methods, particularly when based on regular personal interaction with adults, to help a person change behavior and overcome problems in desired ways. Psychotherapy aims to improve an individual's well-being and mental health, to resolve or mitigate troublesome behaviors, beliefs, compulsions, thoughts, or emotions, and to improve relationships and social skills. There are also numerous types of psychotherapy designed for children and adolescents, such as play therapy. Certain psychotherapies are considered evidence-based for treating some diagnosed mental disorders. Others have been criticized as pseudoscience.

Social work is an academic discipline and practice-based profession that concerns itself with individuals, families, groups, communities and society as a whole in an effort to meet basic needs and enhance social functioning, self-determination, collective responsibility, optimal health, and overall well-being. Social functioning is defined as the ability of an individual to perform their social roles within their own self, their immediate social environment, and the society at large. Social work applies areas, such as sociology, psychology, human biology, political science, health, community development, law, and economics, to work with individuals across the lifespan, engage with client systems, conduct assessments, and develop interventions to solve social problems, personal problems, and bring about social change. Social work practice is often divided into micro-work, which involves working directly with individuals or small groups; and macro-work, which involves working with communities, and fostering change on a larger scale through social policy. Since the 1980s, few universities also started to run social work management programmes to qualify students for the management of social and human service organisations besides classical social work education.

Psychology is an academic and applied discipline involving the scientific study of human mental functions and behavior. Occasionally, in addition or opposition to employing the scientific method, it also relies on symbolic interpretation and critical analysis, although these traditions have tended to be less pronounced than in other social sciences, such as sociology. Psychologists study phenomena such as perception, cognition, emotion, personality, behavior, and interpersonal relationships. Some, especially depth psychologists, also study the unconscious mind.

Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion and thought, which could possibly be understood as a mental disorder. Although many behaviors could be considered as abnormal, this branch of psychology typically deals with behavior in a clinical context. There is a long history of attempts to understand and control behavior deemed to be aberrant or deviant, and there is often cultural variation in the approach taken. The field of abnormal psychology identifies multiple causes for different conditions, employing diverse theories from the general field of psychology and elsewhere, and much still hinges on what exactly is meant by "abnormal". There has traditionally been a divide between psychological and biological explanations, reflecting a philosophical dualism in regard to the mind-body problem. There have also been different approaches in trying to classify mental disorders. Abnormal includes three different categories; they are subnormal, supernormal and paranormal.

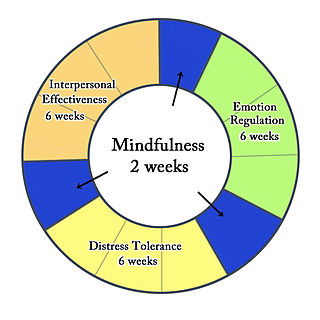

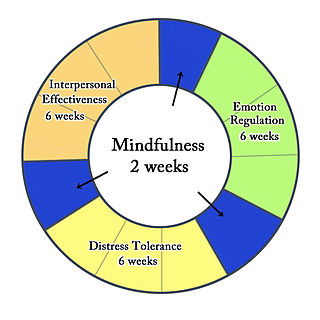

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat borderline personality disorder. There is evidence that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders, suicidal ideation, and for change in behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies, and ultimately balance and synthesize them, in a manner comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of hypothesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

Clinical psychology is an integration of science, theory, and clinical knowledge for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychologically-based distress or dysfunction and to promote subjective well-being and personal development. Central to its practice are psychological assessment, clinical formulation, and psychotherapy, although clinical psychologists also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration. In many countries, clinical psychology is a regulated mental health profession.

Community psychology studies the individuals' contexts within communities and the wider society, and the relationships of the individual to communities and society. Community psychologists seek to understand the quality of life of individuals within groups, organizations and institutions, communities, and society. Their aim is to enhance quality of life through collaborative research and action.

Existential psychotherapy is a form of psychotherapy based on the model of human nature and experience developed by the existential tradition of European philosophy. It focuses on concepts that are universally applicable to human existence including death, freedom, responsibility, and the meaning of life. Instead of regarding human experiences such as anxiety, alienation and depression as implying the presence of mental illness, existential psychotherapy sees these experiences as natural stages in a normal process of human development and maturation. In facilitating this process of development and maturation, existential psychotherapy involves a philosophical exploration of an individual's experiences stressing the individual's freedom and responsibility to facilitate a higher degree of meaning and well-being in their life.

The psychosocial approach looks at individuals in the context of the combined influence that psychological factors and the surrounding social environment have on their physical and mental wellness and their ability to function. This approach is used in a broad range of helping professions in health and social care settings as well as by medical and social science researchers.

Individual psychology is the psychological method or science founded by the Viennese psychiatrist Alfred Adler. The English edition of Adler's work on the subject (1925) is a collection of papers and lectures given mainly in 1912–1914, and covers the whole range of human psychology in a single survey, intended to mirror the indivisible unity of the personality.

A mental health professional is a health care practitioner or social and human services provider who offers services for the purpose of improving an individual's mental health or to treat mental disorders. This broad category was developed as a name for community personnel who worked in the new community mental health agencies begun in the 1970s to assist individuals moving from state hospitals, to prevent admissions, and to provide support in homes, jobs, education, and community. These individuals were the forefront brigade to develop the community programs, which today may be referred to by names such as supported housing, psychiatric rehabilitation, supported or transitional employment, sheltered workshops, supported education, daily living skills, affirmative industries, dual diagnosis treatment, individual and family psychoeducation, adult day care, foster care, family services and mental health counseling.

The Radical Therapist was a journal that emerged in the early 1970s in the context of the counter-culture and the radical U.S. antiwar movement. It was an "alternate journal" in the mental health field that published 12 issues between 1970 and 1972, and "voiced pointed criticisms of psychiatrists during this period". It was run by a group of psychiatrists and activists who believed that mental illness was best treated by social change, not behaviour modification. Their motto was "Therapy means social, political and personal change, not adjustment".

Sexual Identity Therapy (SIT) is a framework to "aid mental health practitioners in helping people arrive at a healthy and personally acceptable resolution of sexual identity and value conflicts." It was invented by Warren Throckmorton and Mark Yarhouse, professors at small conservative evangelical colleges. It has been endorsed by former American Psychological Association president Nick Cummings, psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, and the provost of Wheaton College, Stanton Jones. Sexual identity therapy puts the emphasis on how the client wants to live, identifies the core beliefs and helps the client live according to those beliefs. The creators state that their recommendations "are not sexual reorientation therapy protocols in disguise," but that they "help clients pursue lives they value." They say clients "have high levels of satisfaction with this approach". It is presented as an alternative to both sexual orientation change efforts and gay affirmative psychotherapy.

A clinical formulation, also known as case formulation and problem formulation, is a theoretically-based explanation or conceptualisation of the information obtained from a clinical assessment. It offers a hypothesis about the cause and nature of the presenting problems and is considered an adjunct or alternative approach to the more categorical approach of psychiatric diagnosis. In clinical practice, formulations are used to communicate a hypothesis and provide framework for developing the most suitable treatment approach. It is most commonly used by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists and is deemed to be a core component of these professions. Mental health nurses and social workers may also use formulations.

Feminist psychology is a form of psychology centered on social structures and gender. Feminist psychology critiques historical psychological research as done from a male perspective with the view that males are the norm. Feminist psychology is oriented on the values and principles of feminism.

Family therapy, also referred to as couple and family therapy, marriage and family therapy, family systems therapy, and family counseling, is a branch of psychology that works with families and couples in intimate relationships to nurture change and development. It tends to view change in terms of the systems of interaction between family members.

Robert Rocco Cottone is a psychologist, ethicist, counselor and poet and has been a professor in the Department of Counseling and Family Therapy at the University of Missouri–St. Louis since 1988, where he is a colleague of the social activist Mark Pope. He is also the founder of the Church of Belief Science. Academically, he is best known for his socially oriented theories of counseling and psychotherapy. In the mid-1980s he developed a “systemic theory of vocational rehabilitation”, which constitutes the first comprehensive social theory of vocational rehabilitation. He has been widely cited for his later work on advanced theories of psychotherapy, and he has been rated as having one of the highest publishing records among his peers. He published his first book, Theories and Paradigms of Counseling and Psychotherapy, in 1992, which defined Kuhnian paradigms of mental health treatment. He then developed a fully social model of decision making, the social constructivism model, taking decisions out of the head, so-to-speak, and placing them within the sphere of social discourse. His social theorizing advanced from that of social systems to social constructions.

Clinical mental health counseling is a distinct profession with national standards for education, training, and clinical practice. Clinical mental health counselors operate from a wellness perspective, which emphasizes moving toward optimal human functioning in mind, body, and spirit, and away from distress, dysfunction, and mental illness. Counselors also view wellness and pathology as developmental in nature, and take into consideration all levels of a client's environment when conducting assessment and treatment. Counselors also frequently take a team approach, collaborating with other mental health professionals to provide the most comprehensive care possible for the client.

Trauma-informed feminist therapy is a model of trauma that incorporates sociopolitical context. The diagnosis of Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, was first recognized in 1980 and published in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The original PTSD diagnosis was formulated to fit symptomology of veterans returning home from combat; however, the diagnosis was modified by feminist psychologists treating patients with exposure to childhood sexual assault, chronic abuse, and gender-based trauma. Trauma-informed feminist therapy challenges both the traditional conceptualization of the PTSD diagnosis, as well as the overall standard approach to trauma treatment, by proposing new models of trauma that incorporate sociopolitical context. Initially feminist therapy began in the 1960s during the second wave of feminism and reflected the views of this movement through the conscious acknowledgement of a sexist power structure in American psychotherapy; currently, feminist therapy has expanded to reflect the ideas of the third wave of feminism which posit that the patriarchy is harmful to everyone.