A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects a part of the urinary tract. When it affects the lower urinary tract it is known as a bladder infection (cystitis) and when it affects the upper urinary tract it is known as a kidney infection (pyelonephritis). Symptoms from a lower urinary tract infection include pain with urination, frequent urination, and feeling the need to urinate despite having an empty bladder. Symptoms of a kidney infection include fever and flank pain usually in addition to the symptoms of a lower UTI. Rarely the urine may appear bloody. In the very old and the very young, symptoms may be vague or non-specific.

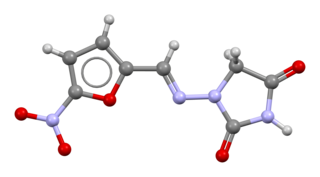

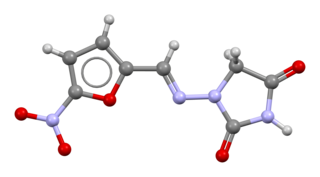

Nitrofurantoin is an antibacterial medication used to treat urinary tract infections, but it is not as effective for kidney infections. It is taken by mouth.

Coagulase is a protein enzyme produced by several microorganisms that enables the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. In the laboratory, it is used to distinguish between different types of Staphylococcus isolates. Importantly, S. aureus is generally coagulase-positive, meaning that a positive coagulase test would indicate the presence of S. aureus or any of the other 11 coagulase-positive Staphylococci. A negative coagulase test would instead show the presence of coagulase-negative organisms such as S. epidermidis or S. saprophyticus. However, it is now known that not all S. aureus are coagulase-positive. Whereas coagulase-positive Staphylococci are usually pathogenic, coagulase-negative Staphylococci are more often associated with opportunistic infection.

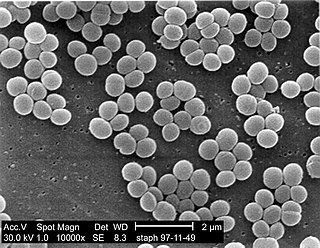

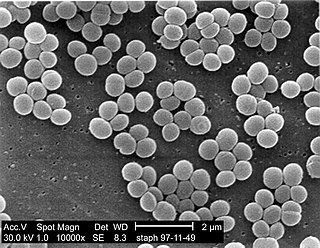

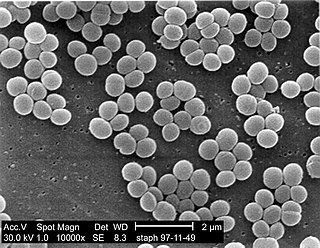

Staphylococcus lugdunensis is a coagulase-negative member of the genus Staphylococcus, consisting of Gram-positive bacteria with spherical cells that appear in clusters.

Staphylococcus haemolyticus is a member of the coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). It is part of the skin flora of humans, and its largest populations are usually found at the axillae, perineum, and inguinal areas. S. haemolyticus also colonizes primates and domestic animals. It is a well-known opportunistic pathogen, and is the second-most frequently isolated CoNS. Infections can be localized or systemic, and are often associated with the insertion of medical devices. The highly antibiotic-resistant phenotype and ability to form biofilms make S. haemolyticus a difficult pathogen to treat. Its most closely related species is Staphylococcus borealis.

Staphylococcus caprae is a Gram-positive, coccus bacteria and a member of the genus Staphylococcus. S. caprae is coagulase-negative. It was originally isolated from goats, but members of this species have also been isolated from human samples.

Staphylococcus hominis is a coagulase-negative member of the bacterial genus Staphylococcus, consisting of Gram-positive, spherical cells in clusters. It occurs very commonly as a harmless commensal on human and animal skin and is known for producing thioalcohol compounds that contribute to body odour. Like many other coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. hominis may occasionally cause infection in patients whose immune systems are compromised, for example by chemotherapy or predisposing illness.

Staphylococcus xylosus is a species of bacteria belonging to the genus Staphylococcus. It is a Gram-positive bacterium that forms clusters of cells. Like most staphylococcal species, it is coagulase-negative and exists as a commensal on the skin of humans and animals and in the environment.

Staphylococcus warneri is a member of the bacterial genus Staphylococcus, consisting of Gram-positive bacteria with spherical cells appearing in clusters. It is catalase-positive, oxidase-negative, and coagulase-negative, and is a common commensal organism found as part of the skin flora on humans and animals. Like other coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. warneri rarely causes disease, but may occasionally cause infection in patients whose immune system is compromised.

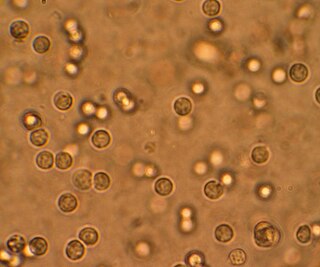

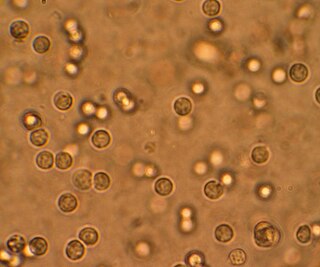

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a Gram-positive bacterium, and one of over 40 species belonging to the genus Staphylococcus. It is part of the normal human microbiota, typically the skin microbiota, and less commonly the mucosal microbiota and also found in marine sponges. It is a facultative anaerobic bacteria. Although S. epidermidis is not usually pathogenic, patients with compromised immune systems are at risk of developing infection. These infections are generally hospital-acquired. S. epidermidis is a particular concern for people with catheters or other surgical implants because it is known to form biofilms that grow on these devices. Being part of the normal skin microbiota, S. epidermidis is a frequent contaminant of specimens sent to the diagnostic laboratory.

A nitrite test is a chemical test used to determine the presence of nitrite ion in solution.

Lysostaphin is a Staphylococcus simulans metalloendopeptidase. It can function as a bacteriocin (antimicrobial) against Staphylococcus aureus.

Bacteriuria is the presence of bacteria in urine. Bacteriuria accompanied by symptoms is a urinary tract infection while that without is known as asymptomatic bacteriuria. Diagnosis is by urinalysis or urine culture. Escherichia coli is the most common bacterium found. People without symptoms should generally not be tested for the condition. Differential diagnosis include contamination.

A staphylococcal infection or staph infection is an infection caused by members of the Staphylococcus genus of bacteria.

Staphylococcus capitis is a coagulase-negative species (CoNS) of Staphylococcus. It is part of the normal flora of the skin of the human scalp, face, neck, scrotum, and ears and has been associated with prosthetic valve endocarditis, but is rarely associated with native valve infection.

Staphylococcus is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria in the family Staphylococcaceae from the order Bacillales. Under the microscope, they appear spherical (cocci), and form in grape-like clusters. Staphylococcus species are facultative anaerobic organisms.

Staphylococcus gallinarum is a Gram-positive, coagulase-negative member of the bacterial genus Staphylococcus consisting of single, paired, and clustered cocci. Strains of this species were first isolated from chickens and a pheasant. The cells contain cell walls with chemical similarity to those of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Since its initial discovery, S. gallinarum has also been found in the saliva of healthy human adults.

Staphylococcus schleiferi is a Gram-positive, cocci-shaped bacterium of the family Staphylococcaceae. It is facultatively anaerobic, coagulase-variable, and can be readily cultured on blood agar where the bacterium tends to form opaque, non-pigmented colonies and beta (β) hemolysis. There exists two subspecies under the species S. schleiferi: Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. schleiferi and Staphylococcus schleiferi subsp. coagulans.

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is a gram positive coccus bacteria of the genus Staphylococcus found worldwide. It is primarily a pathogen for domestic animals, but has been known to affect humans as well. S. pseudintermedius is an opportunistic pathogen that secretes immune modulating virulence factors, has many adhesion factors, and the potential to create biofilms, all of which help to determine the pathogenicity of the bacterium. Diagnoses of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius have traditionally been made using cytology, plating, and biochemical tests. More recently, molecular technologies like MALDI-TOF, DNA hybridization and PCR have become preferred over biochemical tests for their more rapid and accurate identifications. This includes the identification and diagnosis of antibiotic resistant strains.

Georg Peters was a German physician, microbiologist and university professor. From 1992 until his fatal mountain accident he headed the Institute of Medical Microbiology at the University of Münster. He was an internationally recognised expert in the field of staphylococci and the infectious diseases caused by them, to which he had devoted himself since the beginning of his scientific career.