Eurypterids, often informally called sea scorpions, are a group of extinct arthropods that form the order Eurypterida. The earliest known eurypterids date to the Darriwilian stage of the Ordovician period 467.3 million years ago. The group is likely to have appeared first either during the Early Ordovician or Late Cambrian period. With approximately 250 species, the Eurypterida is the most diverse Paleozoic chelicerate order. Following their appearance during the Ordovician, eurypterids became major components of marine faunas during the Silurian, from which the majority of eurypterid species have been described. The Silurian genus Eurypterus accounts for more than 90% of all known eurypterid specimens. Though the group continued to diversify during the subsequent Devonian period, the eurypterids were heavily affected by the Late Devonian extinction event. They declined in numbers and diversity until becoming extinct during the Permian–Triassic extinction event 251.9 million years ago.

Eurypterus is an extinct genus of eurypterid, a group of organisms commonly called "sea scorpions". The genus lived during the Silurian period, from around 432 to 418 million years ago. Eurypterus is by far the most well-studied and well-known eurypterid. Eurypterus fossil specimens probably represent more than 95% of all known eurypterid specimens.

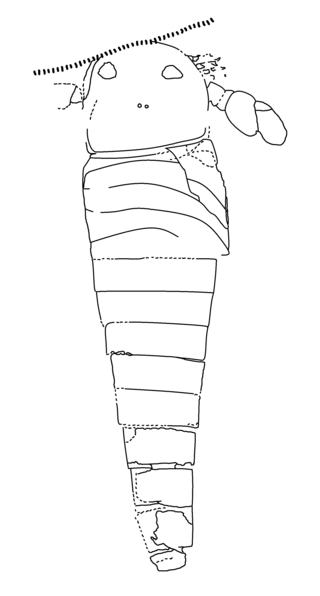

Hibbertopterus is a genus of eurypterid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Hibbertopterus have been discovered in deposits ranging from the Devonian period in Belgium, Scotland and the United States to the Carboniferous period in Scotland, Ireland, the Czech Republic and South Africa. The type species, H. scouleri, was first named as a species of the significantly different Eurypterus by Samuel Hibbert in 1836. The generic name Hibbertopterus, coined more than a century later, combines his name and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

Aglaspidida is an extinct order of aquatic arthropods that were once regarded as primitive chelicerates. However, anatomical comparisons demonstrate that the aglaspidids cannot be accommodated within the chelicerates, and that they lie instead within the Artiopoda, thus placing them closer to the trilobites. Aglaspidida contains the subgroups Aglaspididae and Tremaglaspididae, which are distinguished by the presence of acute/spinose genal angles and a long spiniform tailspine in the Aglaspididae.

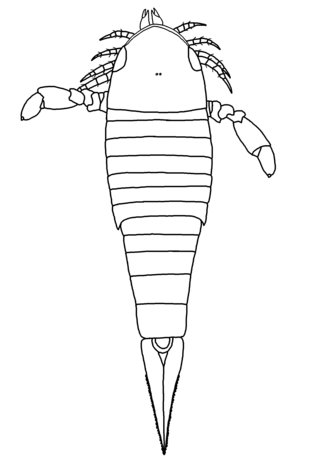

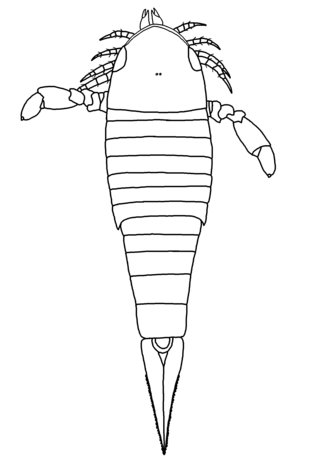

Slimonia is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Slimonia have been discovered in deposits of Silurian age in South America and Europe. Classified as part of the family Slimonidae alongside the related Salteropterus, the genus contains three valid species, S. acuminata from Lesmahagow, Scotland, S. boliviana from Cochabamba, Bolivia and S. dubia from the Pentland Hills of Scotland and one dubious species, S. stylops, from Herefordshire, England. The generic name is derived from and honors Robert Slimon, a fossil collector and surgeon from Lesmahagow.

Carcinosoma is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Carcinosoma are restricted to deposits of late Silurian age. Classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, which the genus lends its name to, Carcinosoma contains seven species from North America and Great Britain.

Alkenopterus is a genus of prehistoric eurypterid classified as part of the family Onychopterellidae. The genus contains two species, A. brevitelson and A. burglahrensis, both from the Devonian of Germany.

Parahughmilleria is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Parahughmilleria have been discovered in deposits of the Devonian and Silurian age in the United States, Canada, Russia, Germany, Luxembourg and Great Britain, and have been referred to several different species. The first fossils of Parahughmilleria, discovered in the Shawangunk Mountains in 1907, were initially assigned to Eurypterus. It would not be until 54 years later when Parahughmilleria would be described.

Helmetia is an extinct genus of arthropod from the middle Cambrian. Its fossils have been found in the Burgess Shale of Canada and the Jince Formation of the Czech Republic.

Unionopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods commonly known as "sea scorpions". Fossils have been registered from the Early Carboniferous period. The genus contains only one species, U. anastasiae, recovered from deposits of Tournaisian to Viséan stages in Kazakhstan. Known from one single specimen which was described in a publication of Russian language with poor illustrations, Unionopterus' affinities are extremely poorly known.

Haikoucaris is a genus of megacheiran arthropod that contains the single species Haikoucaris ercaiensis. It was discovered in the Cambrian Chengjiang biota of China.

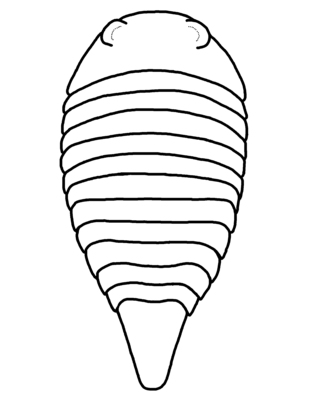

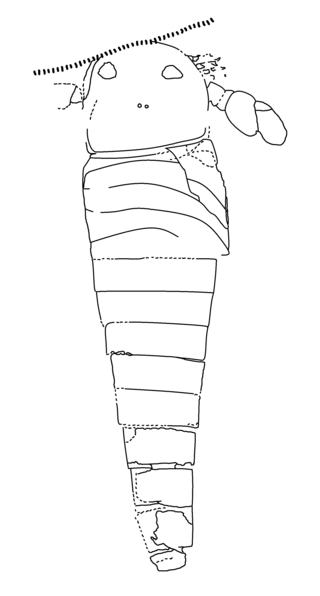

Parapaleomerus is a genus of strabopid of small size found in Chengjiang biota, China. It contains one species, P. sinensis. Unlike the other members of Strabopida, Parapaleomerus lacks dorsal eyes and only possesses ten trunk tergites. The telson has been described as trapezoidal. All the trunk tergites are straight and increasingly curve backwards abaxially from T4–10. Specimens of Parapaleomerus sinesis are typically dorsoventrally compressed. The exoskeleton of P. sinensis has a semi-elliptical head shield that lacks any indication of the presence of dorsal eyes. The largest specimen described is recorded as 9.2 cm long, with a maximum width of 9 cm.

Cucumericrus ("cucumber-leg") is an extinct genus of stem-arthropod. The type and only species is Cucumericrus decoratus, with fossils discovered from the Maotianshan Shales of Yunnan, China.

Slimonidae is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Slimonids were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea and the family most closely related to the derived pterygotid eurypterids, which are famous for their cheliceral claws and great size. Many characteristics of the Slimonidae, such as their flattened and expanded telsons, support a close relationship between the two groups.

Herefordopterus is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Herefordopterus is classified as part of the family Hughmilleriidae, a basal family in the highly derived Pterygotioidea superfamily of eurypterids. Fossils of the single and type species, H. banksii, have been discovered in deposits of Silurian age in Herefordshire and Shropshire, England. The genus is named after Herefordshire, where most of the Herefordopterus fossils have been found. The specific epithet honors Richard Banks, who found several well-preserved specimens, including the first Herefordopterus fossils.

Borchgrevinkium is an extinct genus of chelicerate arthropod. A fossil of the single and type species, B. taimyrensis, has been discovered in deposits of the Early Devonian period in the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Siberia, Russia. The name of the genus honors Carsten Borchgrevink, an Anglo-Norwegian explorer who participated in many expeditions to Antarctica. Borchgrevinkium represents a poorly known genus whose affinities are uncertain.

Strabopidae is the only family of the order Strabopida, an extinct group of arthropods known from the Cambrian period.

Paleomerus is a genus of strabopid, a group of extinct arthropods. It has been found in deposits from the Cambrian period. It is classified in the family Strabopidae of the monotypic order Strabopida. It contains two species, P. hamiltoni from Sweden and P. makowskii from Poland. The generic name is composed by the Ancient Greek words παλαιός (palaiós), meaning "ancient", and μέρος (méros), meaning "part".

Dvulikiaspis is a genus of chasmataspidid, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods. Fossils of the single and type species, D. menneri, have been discovered in deposits of the Early Devonian period in the Krasnoyarsk Krai, Siberia, Russia. The name of the genus is composed by the Russian word двуликий (dvulikij), meaning "two-faced", and the Ancient Greek word ἀσπίς (aspis), meaning "shield". The species name honors the discoverer of the holotype of Dvulikiaspis, Vladimir Vasilyevich Menner.

Luolishania is an extinct genus of lobopodian panarthropod and known from the Lower Cambrian Chiungchussu Formation of the Chengjiang County, Yunnan Province, China. A monotypic genus, it contains one species Luolishania longicruris. It was discovered and described by Hou Xian-Guang and Chen Jun-Yuan in 1989. It is one of the superarmoured Cambrian lobopodians suspected to be either an intermediate form in the origin of velvet worms (Onychophora) or basal to at least Tardigrada and Arthropoda. It is the basis of the family name Luolishaniidae, which also include other related lobopods such as Acinocricus, Collinsium, Facivermis, and Ovatiovermis. Along with Microdictyon, it is the first lobopodian fossil discovered from China.