A clock or chronometer is a device that measures and displays time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month, and the year. Devices operating on several physical processes have been used over the millennia.

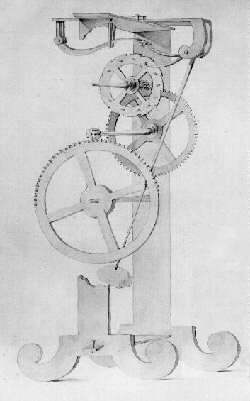

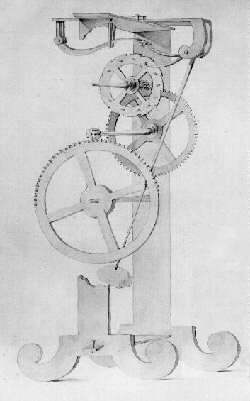

A pendulum clock is a clock that uses a pendulum, a swinging weight, as its timekeeping element. The advantage of a pendulum for timekeeping is that it is an approximate harmonic oscillator: It swings back and forth in a precise time interval dependent on its length, and resists swinging at other rates. From its invention in 1656 by Christiaan Huygens, inspired by Galileo Galilei, until the 1930s, the pendulum clock was the world's most precise timekeeper, accounting for its widespread use. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, pendulum clocks in homes, factories, offices, and railroad stations served as primary time standards for scheduling daily life, work shifts, and public transportation. Their greater accuracy allowed for the faster pace of life which was necessary for the Industrial Revolution. The home pendulum clock was replaced by less-expensive synchronous electric clocks in the 1930s and '40s. Pendulum clocks are now kept mostly for their decorative and antique value.

The second is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as 1⁄86400 of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each. "Minute" comes from the Latin pars minuta prima, meaning "first small part", and "second" comes from the pars minuta secunda, "second small part".

A pendulum is a device made of a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the equilibrium position. When released, the restoring force acting on the pendulum's mass causes it to oscillate about the equilibrium position, swinging back and forth. The time for one complete cycle, a left swing and a right swing, is called the period. The period depends on the length of the pendulum and also to a slight degree on the amplitude, the width of the pendulum's swing.

A watch is a portable timepiece intended to be carried or worn by a person. It is designed to keep a consistent movement despite the motions caused by the person's activities. A wristwatch is designed to be worn around the wrist, attached by a watch strap or other type of bracelet, including metal bands, leather straps, or any other kind of bracelet. A pocket watch is designed for a person to carry in a pocket, often attached to a chain.

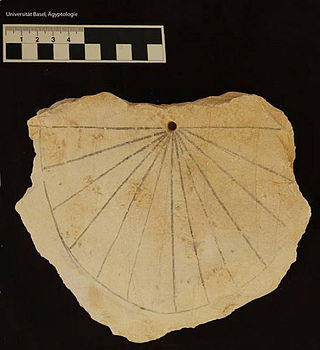

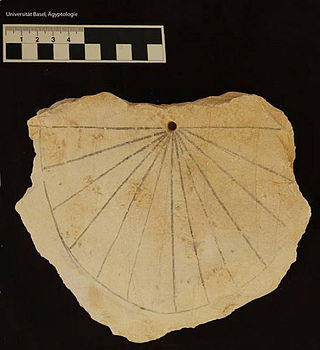

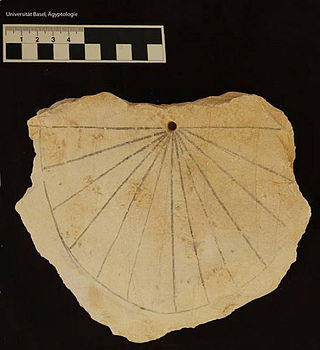

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a flat plate and a gnomon, which casts a shadow onto the dial. As the Sun appears to move through the sky, the shadow aligns with different hour-lines, which are marked on the dial to indicate the time of day. The style is the time-telling edge of the gnomon, though a single point or nodus may be used. The gnomon casts a broad shadow; the shadow of the style shows the time. The gnomon may be a rod, wire, or elaborately decorated metal casting. The style must be parallel to the axis of the Earth's rotation for the sundial to be accurate throughout the year. The style's angle from horizontal is equal to the sundial's geographical latitude.

A water clock or clepsydra is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into or out from a vessel, and where the amount of liquid can then be measured.

A clock face is the part of an analog clock that displays time through the use of a flat dial with reference marks, and revolving pointers turning on concentric shafts at the center, called hands. In its most basic, globally recognized form, the periphery of the dial is numbered 1 through 12 indicating the hours in a 12-hour cycle, and a short hour hand makes two revolutions in a day. A long minute hand makes one revolution every hour. The face may also include a second hand, which makes one revolution per minute. The term is less commonly used for the time display on digital clocks and watches.

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy to the clock's timekeeping element to replace the energy lost to friction during its cycle and keep the timekeeper oscillating. The escapement is driven by force from a coiled spring or a suspended weight, transmitted through the timepiece's gear train. Each swing of the pendulum or balance wheel releases a tooth of the escapement's escape wheel, allowing the clock's gear train to advance or "escape" by a fixed amount. This regular periodic advancement moves the clock's hands forward at a steady rate. At the same time, the tooth gives the timekeeping element a push, before another tooth catches on the escapement's pallet, returning the escapement to its "locked" state. The sudden stopping of the escapement's tooth is what generates the characteristic "ticking" sound heard in operating mechanical clocks and watches.

A grandfather clock is a tall, freestanding, weight-driven pendulum clock, with the pendulum held inside the tower or waist of the case. Clocks of this style are commonly 1.8–2.4 metres (6–8 feet) tall with an enclosed pendulum and weights, suspended by either cables or chains, which have to be occasionally calibrated to keep the proper time. The case often features elaborately carved ornamentation on the hood, which surrounds and frames the dial, or clock face.

A striking clock is a clock that sounds the hours audibly on a bell, gong, or other audible device. In 12-hour striking, used most commonly in striking clocks today, the clock strikes once at 1:00 am, twice at 2:00 am, continuing in this way up to twelve times at 12:00 mid-day, then starts again, striking once at 1:00 pm, twice at 2:00 pm, up to twelve times at 12:00 midnight.

A lantern clock is a type of antique weight-driven wall clock, shaped like a lantern. They were the first type of clock widely used in private homes. They probably originated before 1500 but only became common after 1600; in Britain around 1620. They became obsolete in the 19th century.

Clocks and watches with a 24-hour analog dial have an hour hand that makes one complete revolution, 360°, in a day. The more familiar 12-hour analog dial has an hour hand that makes two complete revolutions in a day.

The history of timekeeping devices dates back to when ancient civilizations first observed astronomical bodies as they moved across the sky. Devices and methods for keeping time have gradually improved through a series of new inventions, starting with measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of liquid in water clocks, to mechanical clocks, and eventually repetitive, oscillatory processes, such as the swing of pendulums. Oscillating timekeepers are used in all modern timepieces.

The ancient Egyptians were one of the first cultures to widely divide days into generally agreed-upon equal parts, using early timekeeping devices such as sundials, shadow clocks, and merkhets . Obelisks were also used by reading the shadow that they make. The clock was split into daytime and nighttime, and then into smaller hours.

A sundial is a device that indicates time by using a light spot or shadow cast by the position of the Sun on a reference scale. As the Earth turns on its polar axis, the sun appears to cross the sky from east to west, rising at sun-rise from beneath the horizon to a zenith at mid-day and falling again behind the horizon at sunset. Both the azimuth (direction) and the altitude (height) can be used to create time measuring devices. Sundials have been invented independently in every major culture and became more accurate and sophisticated as the culture developed.

The Whitehurst & Son sundial was produced in Derby in 1812 by the nephew of John Whitehurst. It is a fine example of a precision sundial telling local apparent time with a scale to convert this to local mean time, and is accurate to the nearest minute. The sundial is now housed in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.

A clock position, or clock bearing, is the direction of an object observed from a vehicle, typically a vessel or an aircraft, relative to the orientation of the vehicle to the observer. The vehicle must be considered to have a front, a back, a left side and a right side. These quarters may have specialized names, such as bow and stern for a vessel, or nose and tail for an aircraft. The observer then measures or observes the angle made by the intersection of the line of sight to the longitudinal axis, the dimension of length, of the vessel, using the clock analogy.

An equation clock is a mechanical clock which includes a mechanism that simulates the equation of time, so that the user can read or calculate solar time, as would be shown by a sundial. The first accurate clocks, controlled by pendulums, were patented by Christiaan Huyghens in 1657. For the next few decades, people were still accustomed to using sundials, and wanted to be able to use clocks to find solar time. Equation clocks were invented to fill this need.

This timeline of time measurement inventions is a chronological list of particularly important or significant technological inventions relating to timekeeping devices and their inventors, where known.