The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA and some of its organelles, and subsequently the partitioning of its cytoplasm and other components into two daughter cells in a process called cell division.

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

Tumor protein P53, also known as p53, cellular tumor antigen p53, the Guardian of the Genome, phosphoprotein p53, tumor suppressor p53, antigen NY-CO-13, or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53), is any isoform of a protein encoded by homologous genes in various organisms, such as TP53 (humans) and Trp53 (mice). This homolog is crucial in multicellular vertebrates, where it prevents cancer formation, and thus functions as a tumor suppressor. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome" because of its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation. Hence TP53 is classified as a tumor suppressor gene.

Retinoblastoma (Rb) is a rare form of cancer that rapidly develops from the immature cells of a retina, the light-detecting tissue of the eye. It is the most common primary malignant intraocular cancer in children, and it is almost exclusively found in young children.

Li–Fraumeni syndrome is a rare, autosomal dominant, hereditary disorder that predisposes carriers to cancer development. It was named after two American physicians, Frederick Pei Li and Joseph F. Fraumeni, Jr., who first recognized the syndrome after reviewing the medical records and death certificates of 648 childhood rhabdomyosarcoma patients. This syndrome is also known as the sarcoma, breast, leukaemia and adrenal gland (SBLA) syndrome.

An oncovirus is a virus that can cause cancer. This term originated from studies of acutely transforming retroviruses in the 1950–60s, when the term "oncornaviruses" was used to denote their RNA virus origin. With the letters "RNA" removed, it now refers to any virus with a DNA or RNA genome causing cancer and is synonymous with "tumor virus" or "cancer virus". The vast majority of human and animal viruses do not cause cancer, probably because of longstanding co-evolution between the virus and its host. Oncoviruses have been important not only in epidemiology, but also in investigations of cell cycle control mechanisms such as the retinoblastoma protein.

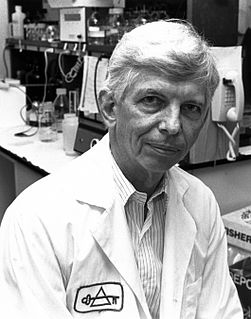

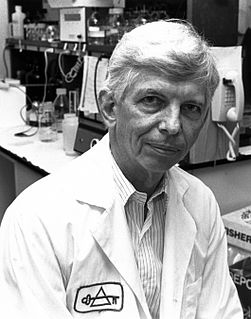

The Knudson hypothesis, also known as the two-hit hypothesis, is the hypothesis that most tumor suppressor genes require both alleles to be inactivated, either through mutations or through epigenetic silencing, to cause a phenotypic change. It was first formulated by Alfred G. Knudson in 1971 and led indirectly to the identification of cancer-related genes. Knudson won the 1998 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award for this work.

Alfred George Knudson, Jr. was an American physician and geneticist specializing in cancer genetics. Among his many contributions to the field was the formulation of the Knudson hypothesis in 1971, which explains the effects of mutation on carcinogenesis.

p73 is a protein related to the p53 tumor protein. Because of its structural resemblance to p53, it has also been considered a tumor suppressor. It is involved in cell cycle regulation, and induction of apoptosis. Like p53, p73 is characterized by the presence of different isoforms of the protein. This is explained by splice variants, and an alternative promoter in the DNA sequence.

Carcinogenesis, also called oncogenesis or tumorigenesis, is the formation of a cancer, whereby normal cells are transformed into cancer cells. The process is characterized by changes at the cellular, genetic, and epigenetic levels and abnormal cell division. Cell division is a physiological process that occurs in almost all tissues and under a variety of circumstances. Normally the balance between proliferation and programmed cell death, in the form of apoptosis, is maintained to ensure the integrity of tissues and organs. According to the prevailing accepted theory of carcinogenesis, the somatic mutation theory, mutations in DNA and epimutations that lead to cancer disrupt these orderly processes by disrupting the programming regulating the processes, upsetting the normal balance between proliferation and cell death. This results in uncontrolled cell division and the evolution of those cells by natural selection in the body. Only certain mutations lead to cancer whereas the majority of mutations do not.

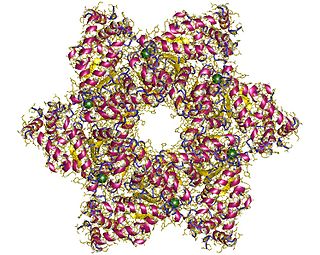

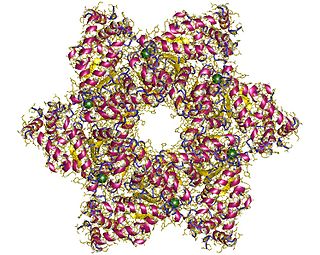

SV40 large T antigen is a hexamer protein that is a dominant-acting oncoprotein derived from the polyomavirus SV40. TAg is capable of inducing malignant transformation of a variety of cell types. The transforming activity of TAg is due in large part to its perturbation of the retinoblastoma (pRb) and p53 tumor suppressor proteins. In addition, TAg binds to several other cellular factors, including the transcriptional co-activators p300 and CBP, which may contribute to its transformation function.

p14ARF is an alternate reading frame protein product of the CDKN2A locus. p14ARF is induced in response to elevated mitogenic stimulation, such as aberrant growth signaling from MYC and Ras (protein). It accumulates mainly in the nucleolus where it forms stable complexes with NPM or Mdm2. These interactions allow p14ARF to act as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting ribosome biogenesis or initiating p53-dependent cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, respectively. p14ARF is an atypical protein, in terms of its transcription, its amino acid composition, and its degradation: it is transcribed in an alternate reading frame of a different protein, it is highly basic, and it is polyubiquinated at the N-terminus.

Cyclin D is a member of the cyclin protein family that is involved in regulating cell cycle progression. The synthesis of cyclin D is initiated during G1 and drives the G1/S phase transition. Cyclin D protein is anywhere from 155 to 477 amino acids in length.

Changes in the genome that allow uncontrolled cell proliferation or cell immortality are responsible for cancer. It is believed that the major changes in the genome that lead to cancer arise from mutations in tumor suppressor genes. In 1997, Kinzler and Bert Vogelstein grouped these cancer susceptibility genes into two classes: "caretakers" and "gatekeepers". In 2004, a third classification of tumor suppressor genes was proposed by Franziska Michor, Yoh Iwasa, and Martin Nowak; "landscaper" genes.

CDKN2A, also known as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, is a gene which in humans is located at chromosome 9, band p21.3. It is ubiquitously expressed in many tissues and cell types. The gene codes for two proteins, including the INK4 family member p16 and p14arf. Both act as tumor suppressors by regulating the cell cycle. p16 inhibits cyclin dependent kinases 4 and 6 and thereby activates the retinoblastoma (Rb) family of proteins, which block traversal from G1 to S-phase. p14ARF activates the p53 tumor suppressor. Somatic mutations of CDKN2A are common in the majority of human cancers, with estimates that CDKN2A is the second most commonly inactivated gene in cancer after p53. Germline mutations of CDKN2A are associated with familial melanoma, glioblastoma and pancreatic cancer. The CDKN2A gene also contains one of 27 SNPs associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease.

Large tumor suppressor kinase 2 (LATS2) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the LATS2 gene.

The retinoblastoma protein is a tumor suppressor protein that is dysfunctional in several major cancers. One function of Rb is to prevent excessive cell growth by inhibiting cell cycle progression until a cell is ready to divide. When the cell is ready to divide, Rb is phosphorylated to pRb, leading to the inactivation of Rb. This process allows cells to enter into the cell cycle state. It is also a recruiter of several chromatin remodeling enzymes such as methylases and acetylases.

Antineoplastic resistance, often used interchangeably with chemotherapy resistance, is the resistance of neoplastic (cancerous) cells, or the ability of cancer cells to survive and grow despite anti-cancer therapies. In some cases, cancers can evolve resistance to multiple drugs, called multiple drug resistance.

A cancer syndrome, or family cancer syndrome, is a genetic disorder in which inherited genetic mutations in one or more genes predispose the affected individuals to the development of cancers and may also cause the early onset of these cancers. Cancer syndromes often show not only a high lifetime risk of developing cancer, but also the development of multiple independent primary tumors.

CpG island hypermethylation is an epigenetic control aberration that is important for gene inactivation in cancer cells. Hypermethylation of CpG islands has been described in almost every type of tumor. Many important cellular pathways, such as DNA repair, cell cycle (p14ARF), apoptosis (DAPK), cell adherence, are inactivated by this epigenetic lesion. Hypermethylation is linked to methyl-binding proteins, DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylase, but the degree to which this process selectively silences tumor suppressor genes remains a vibrant field of study. The list for hypermethylated genes is growing and functional and genetic studies are being performed to determine which hypermethylation events are relevant for tumorigenesis. Basic as well as translational research will be needed to understand the mechanisms and roles of CpG island hypermethylation in cancer.