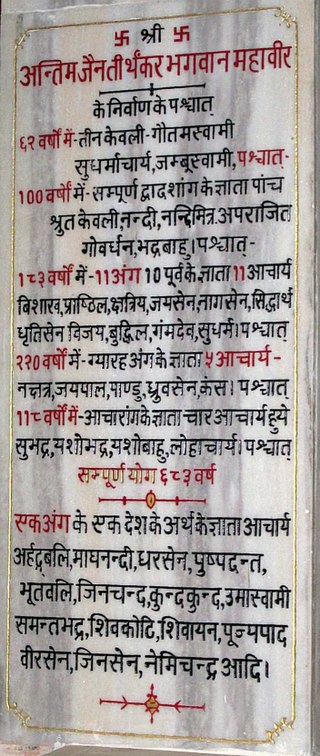

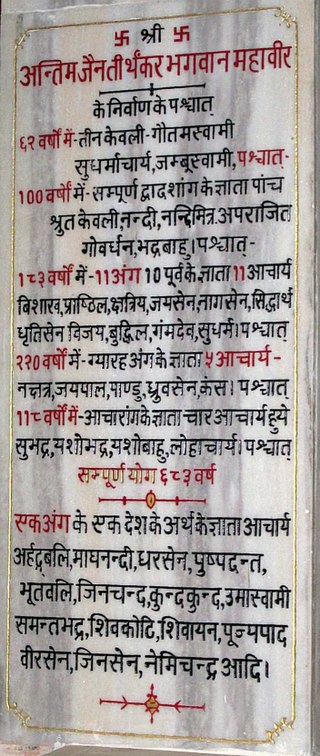

Mahavira, also known as Vardhamana, was the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd Tirthankara Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early 6th century BCE to a royal Jain family of ancient India. His mother's name was Trishala and his father's name was Siddhartha. They were lay devotees of Parshvanatha. Mahavira abandoned all worldly possessions at the age of about 30 and left home in pursuit of spiritual awakening, becoming an ascetic. Mahavira practiced intense meditation and severe austerities for twelve and a half years, after which he attained Kevala Jnana (omniscience). He preached for 30 years and attained moksha (liberation) in the 6th century BCE, although the year varies by sect.

The Śvetāmbara is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the Digambara. Śvetāmbara in Sanskrit means "white-clad", and refers to its ascetics' practice of wearing white clothes, which sets it apart from the Digambara or "sky-clad" Jains whose ascetic practitioners go nude. Śvetāmbaras do not believe that ascetics must practice nudity.

The Kalpa Sūtra is a Jain text containing the biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras, notably Parshvanatha and Mahavira. Traditionally ascribed to Bhadrabahu, which would place it in the 4th century BCE, it was probably put in writing 980 or 993 years after the Nirvana (Moksha) of Mahavira.

Parshvanatha, or Pārśva and Pārasanātha, was the 23rd of 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism. He gained the title of Kalīkālkalpataru.

Ācārya Bhadrabāhu was, according to both the Śvetāmbara and Digambara sects of Jainism, the last Shruta Kevalin in Jainism.

Tattvārthasūtra, meaning "On the Nature [artha] of Reality [tattva]" is an ancient Jain text written by Acharya Umaswami in Sanskrit, sometime between the 2nd- and 5th-century CE.

Jain monasticism refers to the order of monks and nuns in the Jain community and can be divided into two major denominations: the Digambara and the Śvētāmbara. The monastic practices of the two major sects vary greatly, but the major principles of both are identical. Five mahāvratas, from Mahavira's teachings, are followed by all Jain ascetics of both the sects. Historians believe that a united Jain sangha (community) existed before 367 BCE, about 160 years after the moksha (liberation) of Mahavira. The community then gradually divided into the major denominations. However, no evidences indicate when the schism between the Digambaras and the Śvetāmbaras happened.

Anuttaraupapātikadaśāh is the ninth of the 12 Jain āgamas said to be promulgated by Māhavīra himself. Anuttaraupapātikadaśāh translated as "Ten Chapters about the arisers in the Highest Heavens" is said to have been composed by Ganadhara Sudharmaswami as per the Śvetámbara tradition.

Jainism is a religion founded in ancient India. Jains trace their history through twenty-four tirthankara and revere Rishabhanatha as the first tirthankara. The last two tirthankara, the 23rd tirthankara Parshvanatha and the 24th tirthankara Mahavira are considered historical figures. According to Jain texts, the 22nd tirthankara Neminatha lived about 5,000 years ago and was the cousin of Krishna.

A Pattavali, Sthaviravali or Theravali, is a record of a spiritual lineage of heads of monastic orders. They are thus spiritual genealogies. It is generally presumed that two successive names are teacher and pupil. The term is applicable for all Indian religions, but is generally used for Jain monastic orders.

Sthulabhadra was a Jain monk who lived during the 3rd or 4th century BC. He was a disciple of Bhadrabahu and Sambhutavijaya. His father was Sakatala, a minister in Nanda kingdom before the arrival of Chandragupta Maurya. When his brother became the chief minister of the kingdom, Sthulabhadra became a Jain monk and suceeded Bhadrabahu in the Pattavali as per the writings of the Kalpa Sūtra. He is mentioned in the 12th-century Jain text Parisistaparvan by Hemachandra.

Mulachara is a Jain text composed by Acharya Vattakera of the Digambara tradition, around 150 CE. Mulachara discusses anagara-dharma – the conduct of a Digambara monk. It consists twelve chapters and 1,243 verses on. It is also called Digambara Acharanga.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Umaswati, also spelled as Umasvati and known as Umaswami, was an Indian scholar, possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE, known for his foundational writings on Jainism. He authored the Jain text Tattvartha Sutra. Umaswati's work was the first Sanskrit language text on Jain philosophy, and is the earliest extant comprehensive Jain philosophy text accepted as authoritative by all four Jain traditions. His text has the same importance in Jainism as Vedanta Sutras and Yogasutras have in Hinduism.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Jainism is an Indian religion which is traditionally believed to be propagated by twenty-four spiritual teachers known as tirthankara. Broadly, Jainism is divided into two major schools of thought, Digambara and Śvetāmbara. These are further divided into different sub-sects and traditions. While there are differences in practices, the core philosophy and main principles of each sect is the same.

Jains are broadly divided into 2 major groups. These include the Digambara, whose clothing displays symbols of cardinal directions, and the Śvetāmbara who wear white clothes. Both of the groups are similar in their ideology but differ in some aspects.

Sivabhuti was a Jain monk in the 1st century AD who is regarded as the monk who started the Digambara tradition in 82 AD as per the 5th century Śvetāmbara text Avashyak Bhashya written by Jinabhadra. Little is known about him apart from a single story that is written in the ancient Śvetāmbara text. Among several works of research on Jainism, The Jains, a book by Paul Dundas mentions him and the story. However, historical authenticity of his existence or the truthfulness of the story has not been verified.

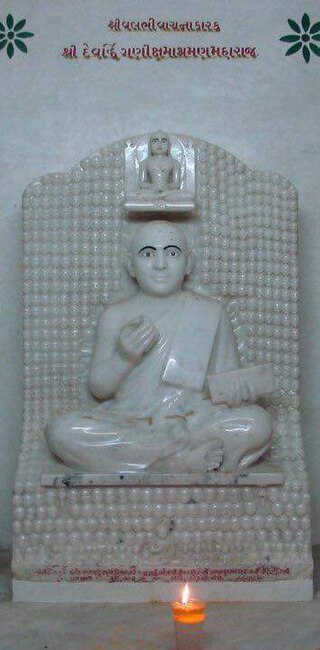

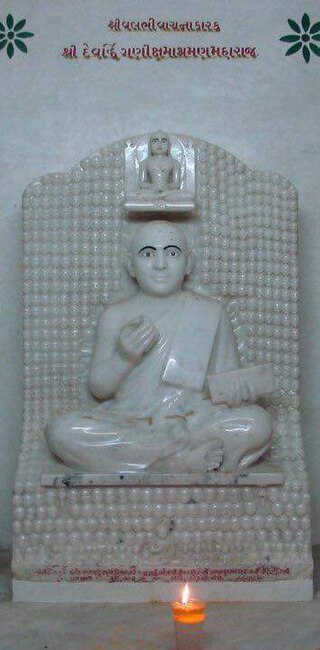

Devardhi or Vachanacharya Devardhigani Kshamashramana or Devavachaka was a Jain ascetic of the Śvetāmbara sect and an author of several Prakrit texts.