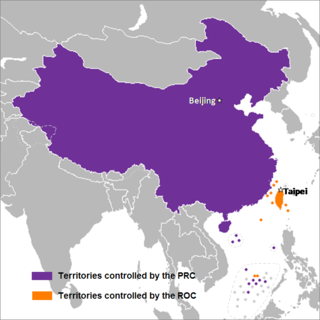

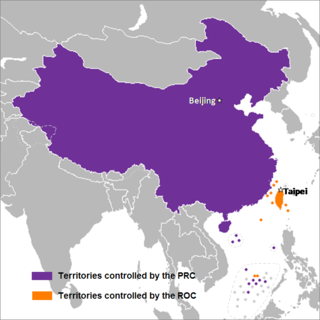

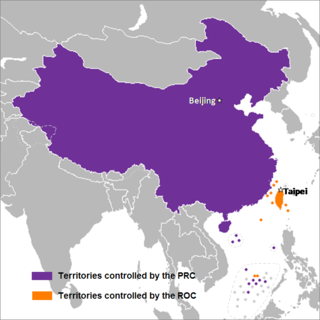

Chinese unification, also known as Cross-Strait unification or Chinese reunification, is the potential unification of territories currently controlled, or claimed, by the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China ("Taiwan") under one political entity, possibly the formation of a political union between the two republics. Together with full Taiwan independence, unification is one of the main proposals to address questions on the political status of Taiwan, which is a central focus of Cross-Strait relations.

One China is a phrase describing the relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) based on Mainland China, and the Republic of China (ROC) based on the Taiwan Area. "One China" asserts that there is only one de jure Chinese nation despite the de facto division between the two rival governments in the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War. The term may refer, in alphabetical order, to one of the following:

Chinese nationalism is a form of nationalism in which asserts that the Chinese people are a nation and promotes the cultural and national unity of all Chinese people. According to Sun Yat-sen's philosophy in the Three Principles of the People, Chinese nationalism is evaluated as multi-ethnic nationalism, which should be distinguished from Han nationalism or local ethnic nationalism.

Han nationalism is a form of ethnic nationalism asserting ethnically Han people as the exclusive constituents of the Chinese nation. It is often in dialogue with other conceptions of Chinese nationalism, often mutually-exclusive or otherwise contradictory ones. Han people are the dominant ethnic group in both states claiming to represent the Chinese nation: the Republic of China and the People's Republic of China.

The relationship between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the United States of America (USA) has been complex and at times tense since the establishment of the PRC and the retreat of the government of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949. Since the normalization of relations in the 1970s, the US–China relationship has been marked by numerous perennial disputes including the political status of Taiwan, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and more recently the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. They have significant economic ties and are significantly intertwined, yet they also have a global hegemonic great power rivalry. As of 2024, China and the United States are the world's second-largest and largest economies by nominal GDP, as well as the largest and second-largest economies by GDP (PPP) respectively. Collectively, they account for 44.2% of the global nominal GDP, and 34.7% of global PPP-adjusted GDP.

Anti-Americanism is a term that can describe several sentiments and positions including opposition to, fear of, distrust of, prejudice against or hatred toward the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general. Anti-Americanism can be contrasted with pro-Americanism, which refers to support, love, or admiration for the United States.

The Sino-Soviet split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) during the Cold War. This was primarily caused by doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications of Marxism–Leninism, as influenced by their respective geopolitics during the Cold War of 1947–1991. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Sino-Soviet debates about the interpretation of orthodox Marxism became specific disputes about the Soviet Union's policies of national de-Stalinization and international peaceful coexistence with the Western Bloc, which Chinese leader Mao Zedong decried as revisionism. Against that ideological background, China took a belligerent stance towards the Western world, and publicly rejected the Soviet Union's policy of peaceful coexistence between the Western Bloc and Eastern Bloc. In addition, Beijing resented the Soviet Union's growing ties with India due to factors such as the Sino-Indian border dispute, and Moscow feared that Mao was too nonchalant about the horrors of nuclear warfare.

The Joint Communiqué of the United States of America and the People's Republic of China, also known as the Shanghai Communiqué (1972), was a diplomatic document issued by the United States of America and the People's Republic of China on February 27, 1972, on the last evening of President Richard Nixon's visit to China.

The time period in China from the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 until the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre is often known as Dengist China. In September 1976, after Chairman Mao Zedong's death, the People's Republic of China was left with no central authority figure, either symbolically or administratively. The Gang of Four was purged, but new Chairman Hua Guofeng insisted on continuing Maoist policies. After a bloodless power struggle, Deng Xiaoping came to the helm to reform the Chinese economy and government institutions in their entirety. Deng, however, was conservative with regard to wide-ranging political reform, and along with the combination of unforeseen problems that resulted from the economic reform policies, the country underwent another political crisis, culminating in the crackdown of massive pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square.

Anti-Chinese sentiment is the fear or dislike of China, Chinese people and/or Chinese culture. In the western world, fear over the increasing economic and military power of China, its technological prowess and cultural reach, as well as international influence, has driven persistent and selectively negative media coverage of China. This is often aided and abetted by policymakers and politicians, whose actions are driven both by prejudice and expedience.

History of foreign relations of China covers diplomatic, military, political and economic relations in History of China from 1800 to the modern era. For the earlier period see Foreign relations of imperial China, and for the current foreign relations of China see Foreign relations of China.

From February 21 to 28, 1972, United States President Richard Nixon visited the People's Republic of China (PRC) in the culmination of his administration's efforts to establish relations with the PRC after years of U.S. diplomatic policy that favored the Republic of China in Taiwan. His visit was the first time a U.S. president had visited the PRC, and his arrival in Beijing ended 25 years of no communication or diplomatic ties between the two countries. Nixon visited the PRC to gain more leverage over relations with the Soviet Union, following the Sino-Soviet split. The normalization of ties culminated in 1979, when the U.S. transferred diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing and established full relations with the PRC.

The concept of Two Chinas refers to the political divide between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC). The PRC was established in 1949 by the Chinese Communist Party, while the ROC was founded in 1912 and retreated to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War.

The aftermath of the Korean War set the tone for Cold War tension between superpowers. The Korean War was important in the development of the Cold War, as it showed that the two superpowers, United States and Soviet Union, could fight a "limited war" in a third country. The "limited war" or "proxy war" strategy was a feature of conflicts such as the Vietnam War and the Soviet War in Afghanistan, as well as wars in Angola, Greece, and the Middle East.

India and Republic of China (ROC) had formal diplomatic relations from 1942 to 1949. After severing diplomatic relations, the bilateral relations have improved since the 1990s, despite both countries not maintaining official diplomatic relations. India only recognises the People's Republic of China (PRC) since 1949. However, India's economic and commercial links as well as people-to-people contacts with Taiwan have expanded in recent years.

Anti-Korean sentiment in China refers to opposition, hostility, hatred, distrust, fear, and general dislike of Korean people or culture in China. This is sometimes referred to in China as the xianhan sentiment, which some have argued has been evoked by perceived Korean arrogance that has challenged the sense of superiority that the Chinese have traditionally associated with their 5,000-year-old civilization.

With the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, American immigration policy towards Chinese emigrants and the highly controversial subject of foreign policy with regard to the PRC became invariably connected. The United States government was presented with the dilemma of what to do with two separate "Chinas". Both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China wanted be seen as the legitimate government and both parties believed that immigration would assist them in doing so.

Korea has had a long history of both resistance against and subordination to Imperial China. Until the onset of Western imperialism in the 19th century, Korea had been part of the sinocentric East Asian regional order.

East Asia–United States relations covers American relations with the region as a whole, as well as summaries of relations with China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and smaller places. It includes diplomatic, military, economic, social and cultural ties. The emphasis is on historical developments.

The Cold War in Asia was a major dimension of the worldwide Cold War that shaped diplomacy and warfare from the mid-1940s to 1991. The main countries involved were the United States, the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, South Korea, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Taiwan. In the late 1950s, divisions between China and the Soviet Union deepened, culminating in the Sino-Soviet split, and the two then vied for control of communist movements across the world, especially in Asia.