History

Apocryphal prayers and hagiographies adapted for "protective" purposes are much more common in the folk tradition than canonical church texts. The use of written texts as amulets began late and their range was relatively narrow, but this did not prevent some of them from becoming widespread. [3]

Apocryphal prayers exist in both oral and written forms. As bookish texts, they retain the features of written language, which leads to the distortion of difficult-to-understand passages. [3] The apocryphal prayers preserved in ancient manuscripts are more ecclesiastical in character than those recorded from the vernacular. [2] Oral "versions" of apocryphal prayers are free translations into spoken language. Some versions may retain the genre form of a prayer, while others take on the features of zagovory. [3]

Some apocryphal prayers are excerpts from popular apocrypha, sometimes distorted or abridged. One source of apocryphal prayers in the Orthodox tradition is Abagar, the first printed book in Bulgarian, authored by Bishop Philip Stanislav. It is a collection of apocrypha, including the New Testament Apocrypha of King Avagar. Among the Southern Slavs, this apocryphal played the role of a protective talisman. Also included in "Abagar" at different times were two apocryphal tales: "And these are the names of the Lord by the number ÕB. These two tales were included at different times: "And these are the names of the Lord's name, numbered ÕB" and "The names of the blessed Virgin Mary numbered ÕB". Lists of these apocrypha texts were also circulated among Eastern Slavic readers. The basis of these texts was a listing of the sacred names of God and the Virgin Mary.

Among texts of bookish origin, both Orthodox and Catholics have a significant proportion of apocryphal prayers that contain accounts of the life and crucifixion of Christ or other significant events of sacred history. [3]

Applications

Apocryphal prayers are used for protective and healing purposes. They were often copied and used as talismans and amulets, which were worn together with a body cross or kept in the house. With the eastern Slavs, the rewriting of such texts by ordinary people did not reduce their sacredness and "effectiveness", while with the southern Slavs great importance was attached to the fact that these "salvation" texts, called "hamajlia", were rewritten by people with a sacred status - Orthodox priests or Muslim clerics.

The use of apocryphal prayers is often determined solely by tradition, so their endings usually contain an explanation of what trouble the prayer protects against. For example: "Whoever knows this prayer, who by memory, who by literacy, will be saved from the enemy, saved from the beast. On the court easy judgment, on the water easy swimming" (Vologda region); "Kto będzie tę modlitewkę odmawiał... Nie zginie wśród burzy i pieronów..." ("Whoever reads these prayers will not be lost amidst storms and lightning" (southeastern Poland). Presumably, these endings go back to the conclusions of Byzantine hagiographies, which received an independent development in Slavic folk traditions. [3]

Examples

The most common prayers and incantations are those for fever. The text usually mentions Saint Sisynius and Herod's daughters - fever. In Malorussian apocryphal prayers the role of Sisynius is often played by Abrahamius or Isaacius. [2]

Exceptionally common is the apocryphal prayer "Our Lady's Dream," which contains the account of Our Lady's torture of Christ on the cross. The text is known in both Catholic and Orthodox traditions in numerous variations, but there is great variation in the purposes for which such texts are used in different cultures. In the popular environment of the Eastern Slavs, this prayer occupies a dominant place and is revered on a par with Our Father and Psalm 90. It was most often recited before going to bed as a general apotropaic text. The text of the "Dream of the Virgin Mary" was worn as a talisman in an amulet together with a body cross.

Apocrypha, listing the sacred names of God and the Virgin Mary, were used as apotrophets, as these names were considered intolerable to the forces of evil. Thus, according to a number of Serbian Bailichka, protection from weshtitsa (female demonological beings) are prayers uttered in time: "I have Jesus!", "Help, God, and Majko Boja!" and others, from vampires - "God help!" and others. The first letters of the name of the Virgin and Jesus Christ, carved above doors, windows, on hiding places with grain, are also considered as amulets against the penetration of evil spirits into the house.

Apocryphal prayers that include an account of the life and crucifixion of Christ are illustrated by the following text from southeastern Poland, uttered for safety during a thunderstorm: "W Jordanie się począł, / W Betlejem narodził, / W Nazaret umarł. / A Słowo stało ciałem / I mieszkało między nami" ("In Jordan began, in Bethlehem was born, in Nazareth died. And Word became body and lived among us"). The account of Christ's anguish for the salvation of mankind projects the idea of universal salvation into a particular situation, so it is thought that in some cases a reference to events from the life of Christ is sufficient for salvation from danger. In Polesia it was believed that when encountering a wolf, it is sufficient to ask him the question: "Wawk, wawk where have you been / as Cyca Khrysta rośpinály?" (or "were you taken?"). [3] Одна из молитв при собирании трав представляет собой искажение и сокращение апокрифа о том, как Христос пахал; одна из молитв от сглаза — переделку апокрифа о рождестве Спасителя. [2]

The popular apocryphal text The Tale of the Twelve Fridays combines two functions. It explains on which Fridays one must fast in order to avoid certain dangers. For example: "1st Friday ... Whoever fasts this Friday will be spared from sinking in the rivers ... 3rd Friday ... Whoever fasts this Friday will be spared from enemies and robbers ..." At the same time, this text is used as a talisman to deliver from various troubles.

The apocryphal prayers also include texts in the form of questions and answers about the structure of the Christian world, built along the lines of Dove Book and having bookish origins. An account of the cosmic nature of the world and an enumeration of the values that ensure its equilibrium and cultural state was perceived as a reliable defense against the forces of chaos. An example of a text known predominantly from the Western Belarusian uniates: "Tell me, what are the twelve? - Twelve Holy Apostles" (hereafter only answers) - "Ozinatsatsi koskal'nykh", - "the ten Commandments of Bosnia, given to us on the mountains of Symon", - "Dziewiec khorów angels", - "Gosem sven prophetü", etc. In the West Belarusian tradition it is believed that the questions are asked by chet, and the answers from these texts save the innocent soul from the unclean force. These verses are called "On the saving of the Chrysian soul, or the conversation of the devil with the little claps". A. N. Veselovsky considered such texts as "catechism of church-school origin, which meets the primary mnemonic requirements of spiritual learning" and found variants of this "tale of numbers" in almost all European traditions. However, the use of such texts as apotropaies in these traditions is unknown. [3]

Apocryphal and folk prayers

Folk Orthodoxy is a broader concept than apocryphal prayers. This category includes canonical prayers in popular culture, fragments of church service endowed with apotropaic function (that is, having non-canonical application), and non-canonical prayers proper. The functioning and anchoring of folk prayers in tradition as apotropies is largely determined not by their own semantics, but by their high sacred status. These texts themselves do not possess apotropaic semantics, and their use as amulets is determined by their ability, as believed, to prevent potential danger. The main part of the corpus of such texts is of book origin and penetrated into the folk tradition with acceptance of Christianity, a smaller part are authentic texts.

In contrast to the Trebniks (containing, in particular, canonical prayers), where each prayer has a strictly defined use, in popular culture canonical Christian prayers usually have no such fixation, and are used as universal apothecaries for all occasions. The main reason for this is that the circle of canonical prayers known in traditional culture is extremely narrow. These include such common prayers with apotropheic semantics as "Let God arise, and His enemies be made waste..." (in the East Slavic folk tradition it is usually called "Sunday Prayer") and the 90th psalm "Alive in aid..." (usually reworked by popular etymology into "Living Help"), as well as "Our Father" and "Virgin Mary, Rejoice..." (in Catholic tradition - "Zdrowiaś, Maria..."). The Lord's Prayer is the universal apotheosis of the Lord's Prayer, which is explained by its unique status: it is the only "nonvirtuous" prayer, that is, given to people by God himself, Christ. At the same time, this prayer is a declaration of man's belonging to the Christian world and of his being under the protection of heavenly powers.

Fragments of a church service, which are in no way connected in meaning with the apotropaic situation in which they are used, also function as amulets. For example, the beginning from the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great, "In you rejoice, O Grace, all things, the angelic assembly and the human race..." may be recited by the master during the driving of the cow to pasture. [3]

Apocrypha are biblical or related writings not forming part of the accepted canon of Scripture. While some might be of doubtful authorship or authenticity, in Christianity, the word apocryphal (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were to be read privately rather than in the public context of church services. Apocrypha were edifying Christian works that were not considered canonical scripture. It was not until well after the Protestant Reformation that the word apocrypha was used by some ecclesiastics to mean "false," "spurious," "bad," or "heretical."

The deuterocanonical books are books and passages considered by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and/or the Assyrian Church of the East to be canonical books of the Old Testament, but which Jews and Protestants regard as apocrypha. They date from 300 BC to 100 AD, before the separation of the Christian church from Judaism. While the New Testament never directly quotes from or names these books, the apostles quoted the Septuagint, which includes them. Some say there is a correspondence of thought, and others see texts from these books being paraphrased, referred, or alluded to many times in the New Testament, depending in large measure on what is counted as a reference.

Powwow, also called Brauche or Braucherei in the Pennsylvania Dutch language, is a vernacular system of North American traditional medicine and folk magic originating in the culture of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Blending aspects of folk religion with healing charms, "powwowing" includes a wide range of healing rituals used primarily for treating ailments in humans and livestock, as well as securing physical and spiritual protection, and good luck in everyday affairs. Although the word "powwow" is Native American, these ritual traditions are of European origin and were brought to colonial Pennsylvania in the transatlantic migrations of German-speaking people from Central Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A practitioner is sometimes referred to as a "Powwower" or Braucher, but terminology varies by region. These folk traditions continue to the present day in both rural and urban settings, and have spread across North America.

Zagоvory is a form of verbal folk magic in Eastern Slavic folklore and mythology. Users of zagоvory use incantations to enchant objects or people.

The New Testament apocrypha are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

The cimaruta is an Italian folk amulet or talisman, traditionally worn around the neck or hung above an infant's bed to ward off the evil eye. Commonly made of silver, the amulet itself consists of several small apotropaic charms, with each individual piece attached to what is supposed to represent a branch of rue—the flowering medicinal herb for which the whole talisman is named, "cimaruta" being a Neapolitan form of cima di ruta: Italian for "sprig of rue".

Apotropaic magic or protective magic is a type of magic intended to turn away harm or evil influences, as in deflecting misfortune or averting the evil eye. Apotropaic observances may also be practiced out of superstition or out of tradition, as in good luck charms, amulets, or gestures such as crossed fingers or knocking on wood. Many different objects and charms were used for protection throughout history.

The biblical apocrypha denotes the collection of apocryphal ancient books thought to have been written some time between 200 BC and AD 100. The Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches include some or all of the same texts within the body of their version of the Old Testament, with Catholics terming them deuterocanonical books. Traditional 80-book Protestant Bibles include fourteen books in an intertestamental section between the Old Testament and New Testament called the Apocrypha, deeming these useful for instruction, but non-canonical. To this date, the Apocrypha are "included in the lectionaries of Anglican and Lutheran Churches". Anabaptists use the Luther Bible, which contains the Apocrypha as intertestamental books; Amish wedding ceremonies include "the retelling of the marriage of Tobias and Sarah in the Apocrypha". Moreover, the Revised Common Lectionary, in use by most mainline Protestants including Methodists and Moravians, lists readings from the Apocrypha in the liturgical calendar, although alternate Old Testament scripture lessons are provided.

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations also includes deuterocanonical books. Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants use different canons, which differ with respect to the texts that are included in the Old Testament.

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's Natural History describes as "an object that protects a person from trouble". Anything can function as an amulet; items commonly so used include statues, coins, drawings, plant parts, animal parts, and written words.

A biblical canon is a set of texts which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible.

A talisman is any object ascribed with religious or magical powers intended to protect, heal, or harm individuals for whom they are made. Talismans are often portable objects carried on someone in a variety of ways, but can also be installed permanently in architecture. Talismans are closely linked with amulets, fulfilling many of the same roles, but a key difference is in their form and materiality, with talismans often taking the form of objects which are inscribed with magic texts.

Folk Orthodoxy refers to the folk religion and syncretic elements present in the Eastern Orthodox communities. It is a subgroup of folk Christianity, similar to Folk Catholicism. Peasants incorporated many pre-Christian (pagan) beliefs and observances, including the coordination of feast days with agricultural life.

Evenki orthography is the orthography of the Evenki language.

Week - In popular tradition of the Slavs personification Sunday as day of the week. It is correlated with Saint Anastasia (in Bulgarians also with Saint Kyriakia. The veneration of the Week is associated with the prohibition of various kinds of work.

Paraskeva Friday is an image based on a personification of Friday as the day of the week and the cult of saints Paraskeva of Iconium, called Friday and Paraskeva of the Balkans. In folk tradition, the image of Paraskeva Friday correlates with the image of Goddess, Saint Anastasia of the Lady of Sorrows, and the Week as a personified image of Sunday.

The Word of a certain Christ-lover and zealot for the right faith is a significant work of ecclesiastical Old East Slavic literature. It is an Orthodox work directed against folk customs and pagan beliefs and rituals.

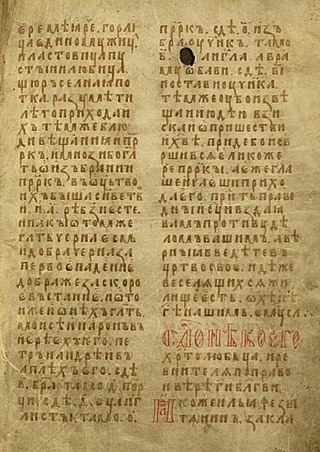

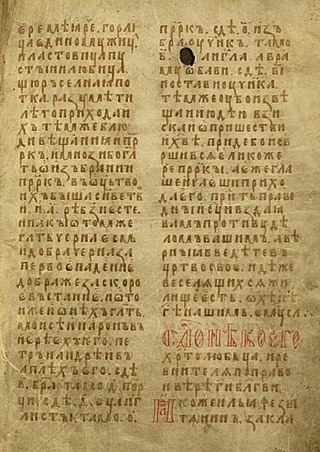

In the Church Slavonic written tradition, the Index of Repudiated Books is a list of writings forbidden to be read by the Orthodox faithful. The works included in this list are renounced. They include apocrypha opposed to Biblical canon. The Slavonic lists originate in translations of the Byzantine lists. In Rus' they have been known since the eleventh century. The Izbornik of Sviatoslav II of Kiev of 1073 contains an index of renounced books and is the earliest bibliographic monument from Rus'. The Index of Repudiated Books may be considered the Orthodox counterpart to the Catholic Index of Prohibited Books.

The Alexievsky Cross is a fourteenth century inlaid stone wayside cross installed on the western wall of the Sophia Cathedral in Weliky Novgorod. It is named for Archbishop Alexei of Novgorod, who originally commissioned it.

The Nut Feast of the Saviour is the third spas feast of the Saviour which celebrates the Holy Mandylion of the Lord. It is celebrated as the afterfeast of the solemnity of the Dormition. After the Honey Feast of the Saviour and the Apple Feast of the Saviour, the Nut feast is therefore placed on August 16 in the Julian calendar and on August 29 in the Gregorian calendar.