Chernobog and Belobog are an alleged pair of Polabian deities. Chernobog appears in Helmold's Chronicle as a god of misfortune worshipped by the Wagri and Obodrites, while Belobog is not mentioned – he was reconstructed in opposition to Chernobog. Both gods also appear in later sources, but they are not considered reliable. Researchers do not agree on the status of Chernobog and Belobog: many scholars recognize the authenticity of these theonyms and explain them, for example, as gods of good and evil; on the other hand, many scholars believe that they are pseudo-deities, and Chernobog may have originally meant "bad fate", and later associated with the Christian devil.

Svarog is a Slavic god of fire and blacksmithing, who was once interpreted as a sky god on the basis of an etymology rejected by modern scholarship. He is mentioned in only one source, the Primary Chronicle, which is problematic in interpretation. He is presented there as the Slavic equivalent of the Greek god Hephaestus. The meaning of his name is associated with fire. He is the father of Dazhbog and Svarozhits.

Svetovit, Sventovit, Svantovit is the god of abundance and war, and the chief god of the Slavic tribe of the Rani, and later of all the Polabian Slavs. His organized cult was located on the island of Rügen, at Cape Arkona, where his main temple was also located. According to the descriptions of medieval chroniclers, the statue representing this god had four heads, a horn and a sword, and to the deity himself were dedicated a white horse, a saddle, a bit, a flag, and eagles. Once a year, after the harvest, a large festival was held in his honor. With the help of a horn and a horse belonging to the god, the priests carried out divinations, and at night the god himself rode a horse to fight his enemies. His name can be translated as "Strong Lord" or "Holy Lord". In the past it was often mistakenly believed that the cult of Svetovit originated from St. Vitus. Among scholars of Slavic mythology, Svetovit is often regarded as a Polabian hypostasis of Pan-Slavic god Perun. His cult collapsed in 1168.

Živa, Zhiva is a mother goddess of one of the tribes belonging to the Obodritic confederation of the Polabian Slavs. The goddess so appears only in the Chronicle of Helmold of Bozov. He described the strengthening of the pagan cult during the reign of Niklot:

Simargl or Sěm and Rgel is an East Slavic god or gods often depicted as a winged dog, mentioned in two sources. The origin and etymology of this/these figure(s) is the subject of considerable debate. The dominant view is to interpret Simargl as a single deity who was borrowed from the Iranian Simurgh. However, this view is criticized, and some researchers propose that the existence of two deities, Sěm and Rgel, should be recognized.

Khors is a Slavic god of uncertain functions mentioned since the 12th century. Generally interpreted as a sun god, sometimes as a moon god. The meaning of the theonym is also unknown: most often his name has been combined with the Iranian word for sun, such as the Persian xoršid, or the Ossetian xor, but modern linguists strongly criticize such an etymology, and other native etymologies are proposed instead.

Porenut is a god with unknown functions mentioned in only two sources: Gesta Danorum and in Knýtlinga saga. The only historical information about this god is the description of a statue depicting him with four faces on his head and a fifth face on his chest, which was held by his chin with his right hand and his forehead with his left hand.

Radogost is, according to medieval chroniclers, the god of the Polabian Slavs, whose temple was located in Rethra. In modern scientific literature, however, the dominant view is that Radogost is a local nickname or a local alternative name of the solar god Svarozhits, who, according to earlier sources, was the chief god of Rethra. Some researchers also believe that the name of the town, where Svarozhits was the main deity, was mistakenly taken for a theonym. A popular local legend in the Czech Republic is related to Radogost.

Podaga is a Polabian deity who had his statue in a temple in Plön. Mentioned only in Helmold's Chronicle, which does not give a depiction or function of the deity.

Among the Slavs there are many modes of idolatry and not all of them coincide with the same kind of superstition. Some create in their temples statues of fantastic forms, such as the idol of Plön, who is called Podaga, others live in forests and groves, as is the case of the god Prone of Oldenburg, of whom no image exists.

Yarovit, Iarovit is a Polabian god of war, worshipped in Vologošč (Circipanians) and Hobolin. Sources give only a brief description of his cult, his main temple was located in Vologošč, where there was a golden shield belonging to Yarovit. By one Christian monk he was identified with the Roman Mars.

Pripegala is a god of the Polabian Slavs, mentioned in a 1108 letter by the Magdeburg Bishop Adelgot, calling for a battle against the pagan Veleti. Among the images of Slavic crimes and atrocities contained in the document was a description of the worship of a god named Pripegala, juxtaposed with the Greek Priapus:

The most fanatical of them say, whenever they wish to divert themselves at feasts, "our Pripegala—they yell ferociously—wants heads, therefore must we perform sacrifices". Pripegala, as they call him, is a lewd Priapus and Belphegor. Thus, after slaughtering the Christians before the alters of their idolatry, they fill the basins with human blood and, howling with terrifying shrieks, say: "Let us make this a day of joy, Christ has been vanquished, the victorious Pripegala has triumphed".

Jesza or Jasza is an alleged Polish god. He was first mentioned around 1405-1412 in the sermons of Lucas of Wielki Koźmin, which warned against the worship of Jesza and other gods during spring rituals and folk performances. His popularity is partly owed Jan Długosz's comparison of him to the Roman god Jupiter. However, contemporary researchers largely reject the authenticity of the deity.

Chernoglav or Chernoglov is the god of victory and war worshipped in Rügen, probably in the town of Jasmund, mentioned together with Svetovit, Rugievit, Turupid, Puruvit and Pizamar in the Knýtlinga saga.

The fifth god was called Pizamar from a place called Jasmund, and was destroyed by fire, There was also Tjarnaglófi, their god of victory who went with them on military campaigns. He had a moustache of silver and resisted longer than the others but they managed to get him there years later. Altogether, they christened five thousand on this expedition.

Svarozhits, Svarozhich is a Slavic god of fire, son of Svarog. One of the few Pan-Slavic gods. He is most likely identical with Radegast, less often identified with Dazhbog.

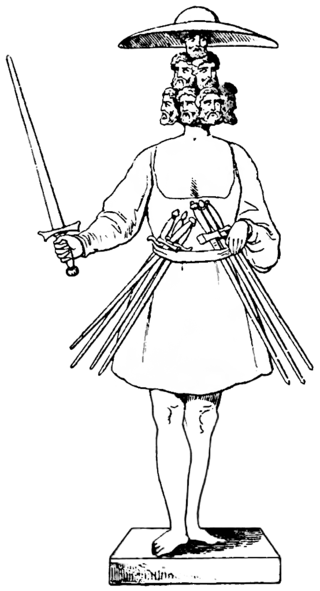

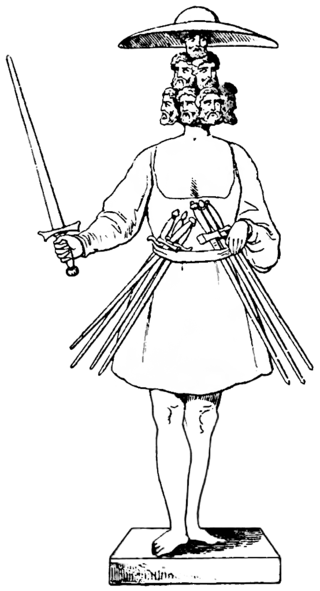

Rugiaevit, Rugievit or Ruyevit is a god of the Slavic Rani worshipped on Rügen, mentioned in only two sources: Gesta Danorum and in Knýtlinga saga. His temple, along with those of Porevit and Porenut, was located in the gord of Charenza, probably today's Garz. The statue of him had seven faces, seven swords at his belt and an eighth one in his hand. Under his lips was a nest of swallows. Mostly associated with the sphere of war, but also sexual.

A zhrets is a priest in the Slavic religion whose name literally means "one who makes sacrifices". The name appears mainly in the East and South Slavic vocabulary, while in the West Slavs it is attested only in Polish. Most information about the Slavic priesthood comes from Latin texts about the paganism of the Polabian Slavs. The descriptions show that they were engaged in offering sacrifices to the gods, divination and determining the dates of festivals. They possessed cosmological knowledge and were a major source of resistance against Christianity.

Dzidzilela, Dzidzileyla, Dzidzilelya is an alleged Polish goddess. First mentioned by Jan Długosz as the Polish equivalent of the Roman goddess Venus, goddess of marriage. Nowadays, the authenticity of the goddess is rejected by most researchers, and it is believed that the theonym was created by recognizing a fragment of folk songs as a proper name.

Hennil or Bendil is an alleged agrarian Slavic god worshipped by the Polabian Slavs. He was mentioned by Bishop Thietmar in his Chronicle as a god who was represented by a staff crowned by a hand holding a ring, which is interpreted as a symbol of fertility. However, there is no general consensus on the authenticity of the deity.

Pizamar is a Slavic deity worshipped on Rügen. His statue was overthrown by the Danes in 1168 together with statues of other gods on Rügen. He is mentioned only in Knýtlinga saga, which, however, does not give the functions of the god or his image. Nowadays his name may be transcribed into English as Pachomir, Pachemir.