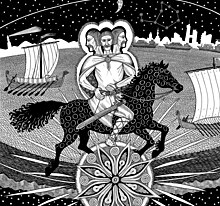

And when the pious Otto destroyed the temples and the images of the idols, the pagan priests stole the golden image of Triglav, which they worshipped as the most important, smuggled it out of the province and delivered it to the safekeeping of a widow who lived on a modest farm, where there was no danger that anybody would come in search of it. Once they had taken this gift to her, she looked after it as if it were the apple of her eye and guarded that pagan idol in the following manner: after making a hole in the trunk of a large tree, she placed the image of Triglav therein, wrapped in a blanket and nobody was allowed to see it, much less touch it; only a small hole was left open in the trunk through which to insert the sacrifice and nobody entered that house unless it was to perform the rituals of the pagan sacrifices [...] And thus, Hermann bought himself a cap and a tunic in the Slavic style and, after many dangers along a difficult road, when he reached the house of that widow, declared that he had not long since succeeded in escaping from the tempestuous jaws of the sea thanks to the invocation of his god Triglav, and that he therefore wished to offer him the sacrifice promised for his salvation and that he had arrived there, led by him, following a miraculous order through unknown stretches of the road. And she says: “If you have been sent by him, I have here the altar which contains our god, enclosed in the hole made in an oak. You may not see him nor touch him, but rather, prostrating yourself before the trunk, take note from a prudent distance of the small hole where you must place the sacrifice you wish to make. And after offering it, once the orifice is reverently closed, go and, if you value your life, do not reveal this conversation to anybody”. He entered joyfully in that place and threw a silver drachma into the hole, so that it would appear, from the sound of the metal, that he had offered a sacrifice. But after throwing it in, he took back out what he had thrown and, by way of homage to Triglav, he offered him a humiliation, specifically, a large gob of spit as a sacrifice. Afterwards, he looked carefully to see if there was any possibility of carrying out the mission for which he had been sent there and he realised that the image of Triglav had been placed in the trunk so carefully and firmly that it could not be taken out or even moved. Whereby, afflicted by no small sorrow, he asked himself anxiously what he should do, saying to himself: “Woe! Why have I travelled so fruitlessly such a long journey by sea! What shall I say to my lord or who will believe that I was here, if I return empty-handed?” And looking around him, he saw Triglav’s saddle hanging nearby on the wall: this was extremely old and now served no purpose and, immediately rushing towards it, he tears the hapless trophy off the wall, hides it and, leaving in the early evening, he hurries to meet up with his lord and his men, tells them what he had done and shows Triglav’s saddle as proof of his loyalty. And thus, the Apostle of the Pomeranians, after holding council with his companions, came to the conclusion that that they should desist in their undertaking, unless it should appear that they were driven less by a zeal for justice than by a greed for gold. After summoning and gathering the tribal chieftains and the elders, they demanded, by means of a solemn oath, that they abandon their cult to Triglav and that, once the image was broken, all of its gold would be used to redeem captives.

– Ebo, Life of Saint Otto, Bishop of Bamberg