The Aboriginal Tasmanians are the Aboriginal people of the Australian state of Tasmania, located south of the mainland. For much of the 20th century, the Tasmanian Aboriginal people were widely, and erroneously, thought of as being an extinct cultural and ethnic group. Contemporary figures (2016) for the number of people of Tasmanian Aboriginal descent vary according to the criteria used to determine this identity, ranging from 6,000 to over 23,000.

The history of Tasmania begins at the end of the most recent ice age when it is believed that the island was joined to the Australian mainland. Little is known of the human history of the island until the British colonisation in the 19th century.

The Tasmanian or Palawa languages were the languages indigenous to the island of Tasmania, used by Aboriginal Tasmanians. The languages were last used for daily communication in the 1830s, although the terminal speaker, Fanny Cochrane Smith, survived until 1905.

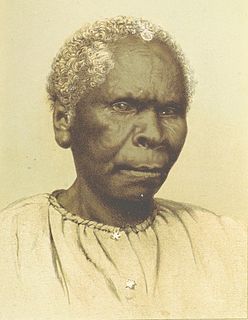

Fanny Cochrane Smith was an Aboriginal Tasmanian, born in December 1834. She is considered to be the last fluent speaker of a Tasmanian language, and her wax cylinder recordings of songs are the only audio recordings of any of Tasmania's indigenous languages. Her recordings were inducted into the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register in 2017.

Kettering is a coastal town on the D'Entrecasteaux Channel opposite Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia. At the 2011 census, Kettering had a population of 984.

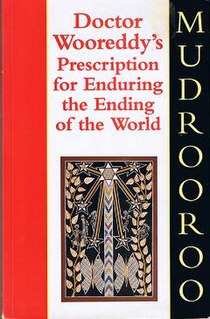

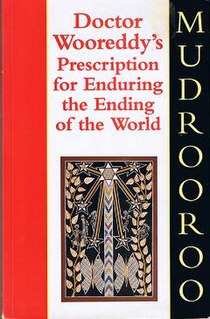

Doctor Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World is an historical novel by Mudrooroo Nyoongah, first published in 1983. Though the protagonist Wooreddy is fictional, the novel deals largely with the real-life George Augustus Robinson, who was sent by Great Britain to Tasmania to act as a conciliator between British settlers and the Tasmanian Aborigines. It also deals with his relationship with "Trugernanna," based on the real-life Trugernanner, the last full-blooded Tasmanian Aborigine. Throughout the narrative the violence of colonisation is documented and explored: "a clear parallel is established between the rape of the Tasmanian Aboriginal women and the metaphorical rape of their land, sacred sites and heritage."

Eastern Tasmanian is an aboriginal language family of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern.

Northern Tasmanian, or Tommeginne (Tommeeginnee), is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern.

Port Sorell is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern. It was spoken near Port Sorell, in the center of the north coast, just east of Northern Tasmanian proper. Dixon & Crowley agree that there is unlikely to be a close connection to other varieties of Tasmanian.

Northwestern Tasmanian, or Peerapper ("Pirapa"), is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern. It was spoken along the west coast of the island, from Macquarie Harbour north to Circular Head and Robbins Island.

Southwestern Tasmanian, or Toogee, is a possible aboriginal language of Tasmania. It is the most poorly attested known variety of Tasmanian, and it is not clear how distinct it was. It was apparently spoken along the west coast of the island, south of Macquarie Harbour.

Northeastern Tasmanian, or Pyemmairre, is an aboriginal language of Tasmania.

North Midland Tasmanian, or Tyerrernotepanner ("Cheranotipana"), was an aboriginal language of northeastern Tasmania, along the Tamar River and inland of Ben Lomond and Great Oyster Bay.

Little Swanport Tasmanian is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern. It was spoken near the modern town of Little Swanport on the east coast. Dixon & Crowley had noted that it appeared to be distinct, but were not sure if it constituted a separate language from other word lists collected near Oyster Bay.

Oyster Bay Tasmanian, or Paredarerme ("Paritarami"), is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern. It was spoken along the central eastern coast of the island by the Oyster Bay tribe, and in the interior by the Big River tribe. Records of the Big River dialect, Lairmairrener ("Lemerina"), indicate that it was no more distinct than the vocabularies collected along the coast around Oyster Bay; indeed, Little Swanport appears to have been a separate language.

Southeast Tasmanian, or Nuenonne ("Nyunoni"), is an aboriginal language of Tasmania in the reconstruction of Claire Bowern. It was spoken along the southeastern mainland of the island by the Bruny tribe.

Tunnerminnerwait (c.1812–1842) was an Australian aboriginal resistance fighter and Parperloihener clansman from Tasmania. He was also known by several other names including Peevay, Jack of Cape Grim, Tunninerpareway and renamed Jack Napoleon Tarraparrura by George Robinson.