The cultural depiction of cats and their relationship to humans is old and stretches back over 9,500 years. Cats are featured in the history of many nations, are the subject of legend, and are a favourite subject of artists and writers.

The cultural depiction of cats and their relationship to humans is old and stretches back over 9,500 years. Cats are featured in the history of many nations, are the subject of legend, and are a favourite subject of artists and writers.

While the exact history of human interaction with cats is still somewhat vague, a shallow grave site discovered in 1983 in Cyprus, dating to 7500 BCE, during the Neolithic period, contains the skeleton of a human, buried ceremonially with stone tools, a lump of iron oxide, and a handful of seashells. In its own tiny grave 40 centimeters (18 inches) from the human grave was an eight-month-old cat, its body oriented in the same westward direction as the human skeleton. Cats are not native to Cyprus. This is evidence that cats were being tamed just as humankind was establishing the first settlements in the part of the Middle East known as the Fertile Crescent. [1]

The lineage of today's cats stems from about 4500 BC and came from Europe and Southeast Asia according to a recent study. Modern cats stem from two major lines of lineage. [2]

Cats, known in ancient Egypt as the mau, played a large role in ancient Egyptian society. They were associated with the goddesses Isis and Bastet. [4] Cats were sacred animals and the goddess Bastet was often depicted in cat form, sometimes taking on the war-like aspect of a lioness. [5] : 220 Killing a cat was absolutely forbidden [3] and the Greek historian Herodotus reports that, whenever a household cat died, the entire family would mourn and shave their eyebrows. [3] Families took their dead cats to the sacred city of Bubastis, [3] where they were embalmed and buried in sacred repositories.

Egyptian hieroglyphics have a character for cat: 𓃠

In Norse mythology, the goddess Freyja was associated with cats. Farmers sought protection for their crops by leaving pans of milk in their fields for Freya's special feline companions, the two grey cats who fought with her and pulled her chariot. [6]

Folklore dating back to as early as 1607 tells that a cat will suffocate a newborn infant by putting its nose to the child's mouth, sucking the breath out of the infant. [7]

Black cats are generally held to be unlucky in the United States and Western Europe, and to portend good luck in the United Kingdom. [7] In the latter country, a black cat entering a house or ship is a good omen, and a sailor's wife should have a black cat for her husband's safety on the sea. [7] [8] Elsewhere, it is considered unlucky if a black cat crosses one's path; black cats have been associated with death and darkness. [4] White cats, bearing the colour of ghosts, are conversely held to be unlucky in the United Kingdom, while tortoiseshell cats are lucky. [7] It is common lore that cats have nine lives. [7] It is a tribute to their perceived durability, their occasional apparent lack of instinct for self-preservation, and their seeming ability to survive falls that would be fatal to other animals.

Domestic cats were probably first introduced to Greece and southern Italy in the fifth century BC by the Phoenicians. [9] The earliest unmistakable evidence of the Greeks having domestic cats comes from two coins from Magna Graecia dating to the mid-fifth century BC showing Iokastos and Phalanthos, the legendary founders of Rhegion and Taras respectively, playing with their pet cats. [10] : 57–58 [11]

Housecats seem to have been extremely rare among the ancient Greeks and Romans; [11] the Greek historian Herodotus expressed astonishment at the domestic cats in Egypt, because he had only ever seen wildcats. [11] Even during later times, weasels were far more commonly kept as pets [11] and weasels, not cats, were seen as the ideal rodent-killers. [11] The usual ancient Greek word for "cat" was ailouros, meaning "thing with the waving tail", [10] : 57 [11] but this word could also be applied to any of the "various long-tailed carnivores kept for catching mice". [11] Cats are rarely mentioned in ancient Greek literature, [11] but Aristotle does remark in his History of Animals that "female cats are naturally lecherous." [10] : 74 [11] The Greek essayist Plutarch linked cats with cleanliness, noting that unnatural odours could make them mad. [12] Pliny linked them with lust, [13] and Aesop with deviousness and cunning. [7]

The Greeks later syncretized their own goddess Artemis with the Egyptian goddess Bastet, adopting Bastet's associations with cats and ascribing them to Artemis. [10] : 77–79 In Ovid's Metamorphoses , when the gods flee to Egypt and take animal forms, the goddess Diana (the Roman equivalent of Artemis) turns into a cat. [10] : 79 Cats eventually displaced ferrets as the pest control of choice because they were more pleasant to have around the house and were more enthusiastic hunters of mice. [14]

During the Middle Ages, many of Artemis' associations with cats were grafted onto the Virgin Mary. [14] Cats are often shown in icons of Annunciation and of the Holy Family [14] and, according to Italian folklore, on the same night that Mary gave birth to Jesus, a cat in Bethlehem gave birth to a kitten. [14]

Vikings used cats as rat catchers and companions.

An old Irish poem about an author (a monk) and his cat, Pangur Bán, was found in a 9th century manuscript. Pangur Bán, 'White Pangur', is the cat's name, Pangur meaning 'a fuller'. In eight verses of four lines each, the author compares the cat's happy hunting with his own scholarly pursuits.

I and Pangur Ban my cat,

'Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

A medieval King of Wales, Hywel Dda (the Good) passed legislation making it illegal to kill or harm a cat. [15]

In Medieval Ypres, cats were used in the winter months to control the vermin infesting the wool stored in the upper floors of the Cloth Hall (Lakenhall). At the start of the spring warm-up, after the wool had been sold, the cats were thrown out of the belfry tower to the town square below, which supposedly symbolised "the killing of evil academics". In today's Kattenstoet (Cat Parade), this was commuted to the throwing of woolen cats from the top of out houses and also the people from the Middle Ages often used to suck on the wool as a sign of good luck.

In the Renaissance, cats were often thought[ clarification needed ] to be witches' familiars in England like Greymalkin, the first witch's familiar in Macbeth 's opening scene.

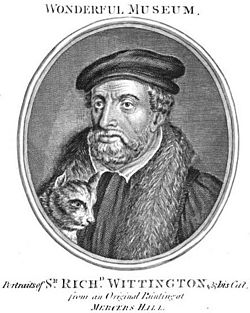

Cats became popular and sympathetic characters in folk tales such as Puss in Boots . [16] One English folk tale in which a cat is given a role of a friend who was betrayed is Dick Whittington and His Cat , which has been adapted for many stage works, including plays, musical comedies and pantomimes. It tells of a poor boy in the 14th century, based on the real-life Richard Whittington, who becomes a wealthy merchant and eventually the Lord Mayor of London because of the ratting abilities of his cat. There is no historical evidence that Whittington had a cat. [16] In the tale, Dick Whittington, a poor orphan finds work at the great house of Mr. Fitzwarren, a rich merchant. His little room infested with rats, Dick acquires a cat, who drives off the rats. One day, Mr. Fitzwarren asked his servants if they wished to send something in his ship, leaving on a journey to a far off port, to trade for gold. Dick decided to sell his only close friend, his cat. In the far-off court, Dick's cat had become a hero by driving very troublesome vermin from the royal court. When Fitzwarren's ship returned, it was loaded with riches. Dick was a rich man. He joined Mr. Fitzwarren in his business and married his daughter Alice, and in time became the Lord Mayor of London. [17]

Unlike in Western countries, cats have been considered good luck in Russia for centuries. Owning a cat, and especially letting one into a new house before the humans move in, is said to bring good fortune. [18] Cats in Orthodox Christianity are the only animals that are allowed to enter the temples. Also, cats were an integral attribute of Russian Orthodox monasteries. According to Russian law, a huge fine was imposed for killing a cat, the same as for a horse or ox.

Many cats have guarded the Hermitage Museum/Winter Palace continually, since Empress Elizabeth's reign, when she was presented by the city of Kazan in Tatarstan five of their best mousers to control the palace's rodent problem. [19] They lived pampered lives and even had special servants until the October Revolution, after which they were cared for by volunteers. Now, they are again looked after by employees. In modern-day Russia there is a group of cats at the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. They have their own press secretary, with about 74 cats of both genders roaming the museum.

Cats that were favored pets during the Chinese Song dynasty were long-haired cats for catching rats, and cats with yellow-and-white fur called 'lion-cats', who were valued simply as cute pets. [20] [21] Cats could be pampered with items bought from the market such as "cat-nests", and were often fed fish that were advertised in the market specifically for cats. [20] [21]

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as section.(July 2021) |

In Japanese folklore, cats are often depicted as supernatural entities, or kaibyō ( かいびょう , "strange cat"). [22] [23]

The maneki-neko of Japan is a figurine often believed to bring good luck to the owner. Literally the beckoning cat, it is often referred to in English as the "good fortune" or "good luck" cat. It is usually a sitting cat with one of its paws raised and bent. Legend in Japan has it that a cat waved a paw at a Japanese landlord, who was intrigued by this gesture and went towards it. A few seconds later a lightning bolt struck where the landlord had been previously standing. [24] The landlord attributed his good fortune to the cat's fortuitous action. A symbol of good luck hence, it is most often seen in businesses to draw in money. In Japan, the flapping of the hand is a "come here" gesture, so the cat is beckoning customers.

There is also a small cat shrine (neko jinja (猫神社)) built in the middle of the Tashirojima island. In the past, the islanders raised silkworms for silk, and cats were kept in order to keep the mouse population down (because mice are a natural predator of silkworms). Fixed-net fishing was popular on the island after the Edo period and fishermen from other areas would come and stay on the island overnight. The cats would go to the inns where the fishermen were staying and beg for scraps. Over time, the fishermen developed a fondness for the cats and would observe the cats closely, interpreting their actions as predictions of the weather and fish patterns. One day, when the fishermen were collecting rocks to use with the fixed-nets, a stray rock fell and killed one of the cats. The fishermen, feeling sorry for the loss of the cat, buried it and enshrined it at this location on the island.

This is not the only cat shrine in Japan, however. Others include Nambujinja in the Niigata Prefecture and one at the entrance of Kyotango City, Kyoto. [25]

Another Japanese legend of cats is the nekomata: when a cat lives to a certain age, it grows another tail and can stand up and speak in a human language.

Hello Kitty, created by Yuko Yamaguchi, is a contemporary cat icon. The character made its debut in 1974 and has since become a global staple of Japanese culture; the merchandise is available all over the world. According to Sanrio, the official licenser, designer, and producer of Hello Kitty merchandise, the character is a cartoon version of a little girl. In her fictional life, she is from the outskirts of London and a part of the Sanrio universe. [26]

Although no species are sacred in Islam, cats are revered by Muslims. Some Western writers have stated Muhammad had a favorite cat, Muezza. [27] He is reported to have loved cats so much that, "he would do without his cloak rather than disturb one that was sleeping on it". [28] The story has no origin in early Muslim writers, and seems to confuse a story of a later Sufi saint, Ahmed ar-Rifa'i, centuries after Muhammad. [29]

Cats have also featured prominently in modern culture. For example, a cat named Mimsey was used by MTM Enterprises as their mascot and features in their logo as a spoof of the MGM lion. [30] By 1990, the New York Times said that cats had become the most popular subject depicted on gift items (such as coasters, napkins, jewelry, and bookends), and that an estimated 1,000 stores in the United States sold nothing but cat-related items. [31]

On the Internet, cats frequently appear often as memes and other humor; and on social media people frequently post pictures of their own cats.