Coercion involves compelling a party to act in an involuntary manner through the use of threats, including threats to use force against that party. It involves a set of forceful actions which violate the free will of an individual in order to induce a desired response. These actions may include extortion, blackmail, or even torture and sexual assault. Common-law systems codify the act of violating a law while under coercion as a duress crime.

A tort is a civil wrong, other than breach of contract, that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable by the state. While criminal law aims to punish individuals who commit crimes, tort law aims to compensate individuals who suffer harm as a result of the actions of others. Some wrongful acts, such as assault and battery, can result in both a civil lawsuit and a criminal prosecution in countries where the civil and criminal legal systems are separate. Tort law may also be contrasted with contract law, which provides civil remedies after breach of a duty that arises from a contract. Obligations in both tort and criminal law are more fundamental and are imposed regardless of whether the parties have a contract.

An affirmative defense to a civil lawsuit or criminal charge is a fact or set of facts other than those alleged by the plaintiff or prosecutor which, if proven by the defendant, defeats or mitigates the legal consequences of the defendant's otherwise unlawful conduct. In civil lawsuits, affirmative defenses include the statute of limitations, the statute of frauds, waiver, and other affirmative defenses such as, in the United States, those listed in Rule 8 (c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In criminal prosecutions, examples of affirmative defenses are self defense, insanity, entrapment and the statute of limitations.

Intimidation is a behaviour and legal wrong which usually involves deterring or coercing an individual by threat of violence. It is in various jurisdictions a crime and a civil wrong (tort). Intimidation is similar to menacing, coercion, terrorizing and assault in the traditional sense.

In common law, assault is the tort of acting intentionally, that is with either general or specific intent, causing the reasonable apprehension of an immediate harmful or offensive contact. Assault requires intent, it is considered an intentional tort, as opposed to a tort of negligence. Actual ability to carry out the apprehended contact is not necessary. 'The conduct forbidden by this tort is an act that threatens violence.'

A legal remedy, also referred to as judicial relief or a judicial remedy, is the means with which a court of law, usually in the exercise of civil law jurisdiction, enforces a right, imposes a penalty, or makes another court order to impose its will in order to compensate for the harm of a wrongful act inflicted upon an individual.

A civil penalty or civil fine is a financial penalty imposed by a government agency as restitution for wrongdoing. The wrongdoing is typically defined by a codification of legislation, regulations, and decrees. The civil fine is not considered to be a criminal punishment, because it is primarily sought in order to compensate the state for harm done to it, rather than to punish the wrongful conduct. As such, a civil penalty, in itself, will not carry a punishment of imprisonment or other legal penalties.

The Virginia General District Court (GDC) is the lowest level of the Virginia court system, and is the court that most Virginians have contact with. The jurisdiction of the GDC is generally limited to traffic cases and other misdemeanors, civil cases involving amounts of under $25,000. There are 32 GDC districts, each having at least one judge, and each having a clerk of the court and a courthouse with courtroom facilities.

Tortious interference, also known as intentional interference with contractual relations, in the common law of torts, occurs when one person intentionally damages someone else's contractual or business relationships with a third party, causing economic harm. As an example, someone could use blackmail to induce a contractor into breaking a contract; they could threaten a supplier to prevent them from supplying goods or services to another party; or they could obstruct someone's ability to honor a contract with a client by deliberately refusing to deliver necessary goods.

In English law, the defence of necessity recognises that there may be situations of such overwhelming urgency that a person must be allowed to respond by breaking the law. There have been very few cases in which the defence of necessity has succeeded, and in general terms there are very few situations where such a defence could even be applicable. The defining feature of such a defence is that the situation is not caused by another person and that the accused was in genuine risk of immediate harm or danger.

Duress in English law is a complete common law defence, operating in favour of those who commit crimes because they are forced or compelled to do so by the circumstances, or the threats of another. The doctrine arises not only in criminal law but also in civil law, where it is relevant to contract law and trusts law.

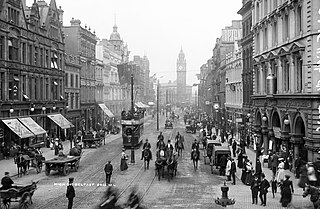

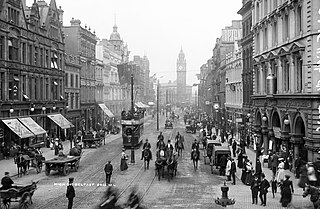

Quinn v Leathem [1901] UKHL 2, is a case on economic tort and is an important case historically for British labour law. It concerns the tort of "conspiracy to injure". The case was a significant departure from previous practices, and was reversed by the Trade Disputes Act 1906. However, the issue of secondary action was later restricted from the Employment Act 1980, and now the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. The case was heavily controversial at the time, and generated a large amount of academic discussion, notably by Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, which continued long after it was overturned.

In the field of criminal law, there are a variety of conditions that will tend to negate elements of a crime, known as defenses. The label may be apt in jurisdictions where the accused may be assigned some burden before a tribunal. However, in many jurisdictions, the entire burden to prove a crime is on the prosecution, which also must prove the absence of these defenses, where implicated. In other words, in many jurisdictions the absence of these so-called defenses is treated as an element of the crime. So-called defenses may provide partial or total refuge from punishment.

Marital coercion was a defence to most crimes under English criminal law and under the criminal law of Northern Ireland. It is similar to duress. It was abolished in England and Wales by section 177 of the Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, which came into force on 13 May 2014. The abolition does not apply in relation to offences committed before that date.

Unconscionability in English law is a field of contract law and the law of trusts, which precludes the enforcement of voluntary obligations unfairly exploiting the unequal power of the consenting parties. "Inequality of bargaining power" is another term used to express essentially the same idea for the same area of law, which can in turn be further broken down into cases on duress, undue influence and exploitation of weakness. In these cases, where someone's consent to a bargain was only procured through duress, out of undue influence or under severe external pressure that another person exploited, courts have felt it was unconscionable to enforce agreements. Any transfers of goods or money may be claimed back in restitution on the basis of unjust enrichment subject to certain defences.

Barton v Armstrong is a Privy Council decision heard on appeal from the Court of Appeal of New South Wales, relating to duress and pertinent to case law under Australian and English contract law.

The criminal law of the United States is a manifold system of laws and practices that connects crimes and consequences. In comparison, civil law addresses non-criminal disputes. The system varies considerably by jurisdiction, but conforms to the US Constitution. Generally there are two systems of criminal law to which a person maybe subject; the most frequent is state criminal law, and the other is federal law.

The eggshell skull rule is a well-established legal doctrine in common law, used in some tort law systems, with a similar doctrine applicable to criminal law. The rule states that, in a tort case, the unexpected frailty of the injured person is not a valid defense to the seriousness of any injury caused to them.

The South African law of delict engages primarily with 'the circumstances in which one person can claim compensation from another for harm that has been suffered'. JC Van der Walt and Rob Midgley define a delict 'in general terms [...] as a civil wrong', and more narrowly as 'wrongful and blameworthy conduct which causes harm to a person'. Importantly, however, the civil wrong must be an actionable one, resulting in liability on the part of the wrongdoer or tortfeasor.

Rape laws vary across the United States jurisdictions. However, rape is federally defined for statistical purposes as:

Penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.