Convex

Cuboid

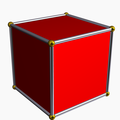

A hexahedron that is combinatorially equivalent to a cube may be called a cuboid, although this term is often used more specifically to mean a rectangular cuboid, a hexahedron with six rectangular sides. A cuboid possess 8 vertices, 8 faces and 12 edges. Different types of cuboids include the ones depicted and linked below.

| Cuboids | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Cube (square) | Rectangular cuboid (three pairs of rectangles) | Trigonal trapezohedron (congruent rhombi) | Trigonal trapezohedron (congruent quadrilaterals) | Quadrilateral frustum (apex-truncated square pyramid) | Parallelepiped (three pairs of parallelograms) | Rhombohedron (three pairs of rhombi) |

Others

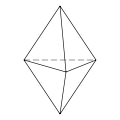

There are seven topologically distinct convex hexahedra, [1] the cuboid and six others, which are depicted below. One of these is chiral, in the sense that it cannot be deformed into its mirror image.

| Image |  |   |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Triangular bipyramid | Pentagonal pyramid | Doubly truncated tetrahedron [2] | |||

| Features |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Properties | Simplicial | Dome |