Rickets, scientific nomenclature: rachitis, is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children and is caused by either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stunted growth, bone pain, large forehead, and trouble sleeping. Complications may include bone deformities, bone pseudofractures and fractures, muscle spasms, or an abnormally curved spine. The analogous condition in adults is osteomalacia.

Osteopetrosis, literally 'stone bone', also known as marble bone disease or Albers-Schönberg disease, is an extremely rare inherited disorder whereby the bones harden, becoming denser, in contrast to more prevalent conditions like osteoporosis, in which the bones become less dense and more brittle, or osteomalacia, in which the bones soften. Osteopetrosis can cause bones to dissolve and break.

Osteomalacia is a disease characterized by the softening of the bones caused by impaired bone metabolism primarily due to inadequate levels of available phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D, or because of resorption of calcium. The impairment of bone metabolism causes inadequate bone mineralization.

Hyperparathyroidism is an increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels in the blood. This occurs from a disorder either within the parathyroid glands or as response to external stimuli. Symptoms of hyperparathyroidism are caused by inappropriately normal or elevated blood calcium excreted from the bones and flowing into the blood stream in response to increased production of parathyroid hormone. In healthy people, when blood calcium levels are high, parathyroid hormone levels should be low. With long-standing hyperparathyroidism, the most common symptom is kidney stones. Other symptoms may include bone pain, weakness, depression, confusion, and increased urination. Both primary and secondary may result in osteoporosis.

Osteogenesis imperfecta, colloquially known as brittle bone disease, is a group of genetic disorders that all result in bones that break easily. The range of symptoms—on the skeleton as well as on the body's other organs—may be mild to severe. Symptoms found in various types of OI include whites of the eye (sclerae) that are blue instead, short stature, loose joints, hearing loss, breathing problems and problems with the teeth. Potentially life-threatening complications, all of which become more common in more severe OI, include: tearing (dissection) of the major arteries, such as the aorta; pulmonary valve insufficiency secondary to distortion of the ribcage; and basilar invagination.

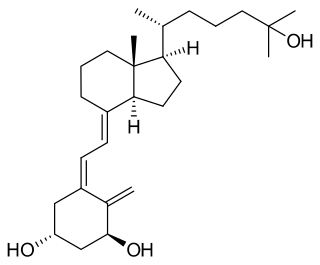

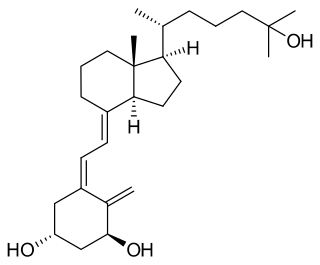

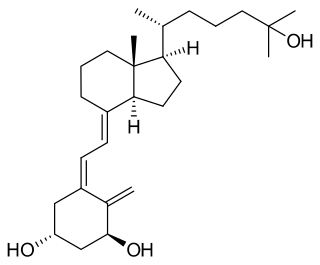

Calcitriol is a hormone and the active form of vitamin D, normally made in the kidney. It is also known as 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. It binds to and activates the vitamin D receptor in the nucleus of the cell, which then increases the expression of many genes. Calcitriol increases blood calcium mainly by increasing the uptake of calcium from the intestines.

Renal osteodystrophy is currently defined as an alteration of bone morphology in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). It is one measure of the skeletal component of the systemic disorder of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). The term "renal osteodystrophy" was coined in 1943, 60 years after an association was identified between bone disease and kidney failure.

Renal tubular acidosis (RTA) is a medical condition that involves an accumulation of acid in the body due to a failure of the kidneys to appropriately acidify the urine. In renal physiology, when blood is filtered by the kidney, the filtrate passes through the tubules of the nephron, allowing for exchange of salts, acid equivalents, and other solutes before it drains into the bladder as urine. The metabolic acidosis that results from RTA may be caused either by insufficient secretion of hydrogen ions into the latter portions of the nephron or by failure to reabsorb sufficient bicarbonate ions from the filtrate in the early portion of the nephron. Although a metabolic acidosis also occurs in those with chronic kidney disease, the term RTA is reserved for individuals with poor urinary acidification in otherwise well-functioning kidneys. Several different types of RTA exist, which all have different syndromes and different causes. RTA is usually an incidental finding based on routine blood draws that show abnormal results. Clinically, patients may present with vague symptoms such as dehydration, mental status changes, or delayed growth in adolescents.

An osteochondrodysplasia, or skeletal dysplasia, is a disorder of the development of bone and cartilage. Osteochondrodysplasias are rare diseases. About 1 in 5,000 babies are born with some type of skeletal dysplasia. Nonetheless, if taken collectively, genetic skeletal dysplasias or osteochondrodysplasias comprise a recognizable group of genetically determined disorders with generalized skeletal affection. These disorders lead to disproportionate short stature and bone abnormalities, particularly in the arms, legs, and spine. Skeletal dysplasia can result in marked functional limitation and even mortality.

X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) is an X-linked dominant form of rickets that differs from most cases of dietary deficiency rickets in that vitamin D supplementation does not cure it. It can cause bone deformity including short stature and genu varum (bow-leggedness). It is associated with a mutation in the PHEX gene sequence (Xp.22) and subsequent inactivity of the PHEX protein. PHEX mutations lead to an elevated circulating (systemic) level of the hormone FGF23 which results in renal phosphate wasting, and local elevations of the mineralization/calcification-inhibiting protein osteopontin in the extracellular matrix of bones and teeth. An inactivating mutation in the PHEX gene results in an increase in systemic circulating FGF23, and a decrease in the enzymatic activity of the PHEX enzyme which normally removes (degrades) mineralization-inhibiting osteopontin protein; in XLH, the decreased PHEX enzyme activity leads to an accumulation of inhibitory osteopontin locally in bones and teeth to block mineralization which, along with renal phosphate wasting, both cause osteomalacia and odontomalacia.

Phosphate-regulating endopeptidase homolog X-linked also known as phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X chromosome or metalloendopeptidase homolog PEX is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PHEX gene. This gene contains 18 exons and is located on the X chromosome.

Bone disease refers to the medical conditions which affect the bone.

Alkaline phosphatase, tissue-nonspecific isozyme (TNAP) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ALPL gene.

A pathologic fracture is a bone fracture caused by weakness of the bone structure that leads to decrease mechanical resistance to normal mechanical loads. This process is most commonly due to osteoporosis, but may also be due to other pathologies such as cancer, infection, inherited bone disorders, or a bone cyst. Only a small number of conditions are commonly responsible for pathological fractures, including osteoporosis, osteomalacia, Paget's disease, Osteitis, osteogenesis imperfecta, benign bone tumours and cysts, secondary malignant bone tumours and primary malignant bone tumours.

Oncogenic osteomalacia, also known as tumor-induced osteomalacia or oncogenic hypophosphatemic osteomalacia, is an uncommon disorder resulting in increased renal phosphate excretion, hypophosphatemia and osteomalacia. It may be caused by a phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor. Symptoms typically include crushing fatigue, severe muscle weakness and brain fog due to the low circulating levels of serum phosphate.

Vitamin D deficiency or hypovitaminosis D is a vitamin D level that is below normal. It most commonly occurs in people when they have inadequate exposure to sunlight, particularly sunlight with adequate ultraviolet B rays (UVB). Vitamin D deficiency can also be caused by inadequate nutritional intake of vitamin D; disorders that limit vitamin D absorption; and disorders that impair the conversion of vitamin D to active metabolites, including certain liver, kidney, and hereditary disorders. Deficiency impairs bone mineralization, leading to bone-softening diseases, such as rickets in children. It can also worsen osteomalacia and osteoporosis in adults, increasing the risk of bone fractures. Muscle weakness is also a common symptom of vitamin D deficiency, further increasing the risk of falls and bone fractures in adults. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with the development of schizophrenia.

Elevated alkaline phosphatase occurs when levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) exceed the reference range. This group of enzymes has a low substrate specificity and catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphate esters in a basic environment. The major function of alkaline phosphatase is transporting chemicals across cell membranes. Alkaline phosphatases are present in many human tissues, including bone, intestine, kidney, liver, placenta and white blood cells. Damage to these tissues causes the release of ALP into the bloodstream. Elevated levels can be detected through a blood test. Elevated alkaline phosphate is associated with certain medical conditions or syndromes. It serves as a significant indicator for certain medical conditions, diseases and syndromes.

Asfotase alfa, sold under the brand name Strensiq, is a medication used in the treatment of people with perinatal/infantile- and juvenile-onset hypophosphatasia.

Phosphate diabetes is a rare, congenital, hereditary disorder associated with inadequate tubular reabsorption that affects the way the body processes and absorbs phosphate. Also named as X-linked dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (XLH), this disease is caused by a mutation in the X-linked PHEX gene, which encodes for a protein that regulates phosphate levels in the human body. phosphate is an essential mineral which plays a significant role in the formation and maintenance of bones and teeth, energy production and other important cellular processes. phosphate diabetes is a condition that falls under the category of tubulopathies, which refers to the pathologies of the renal tubules. The mutated PHEX gene causes pathological elevations in fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a hormone that regulates phosphate homeostasis by decreasing the reabsorption of phosphate in the kidneys.

Michael A. Levine is an American physician, scientist, academic, and author. He is an emeritus Professor of Pediatrics and Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.