Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Chad face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in the country. Before the new penal code took effect in August 2017, homosexual activity between adults had never been criminalised. There is no legal protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Mali face legal and societal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Although same-sex sexual activity is not illegal in Mali, LGBT people face widespread discrimination among the broader population. According to the 2007 Pew Global Attitudes Project, 98 percent of Malian adults believed that homosexuality is considered something society should not accept, which was the highest rate of non-acceptance in the 45 countries surveyed. The Constitution of Mali has outlawed same-sex marriage since 2023.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Republic of the Congo face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of homosexuality are legal in the Republic of the Congo, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples, with reports of discrimination and abuses towards LGBT people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in France are some of the most progressive by world standards. Although same-sex sexual activity was a capital crime that often resulted in the death penalty during the Ancien Régime, all sodomy laws were repealed in 1791 during the French Revolution. However, a lesser-known indecent exposure law that often targeted LGBT people was introduced in 1960, before being repealed in 1980.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Andorra have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now considered generally progressive. Civil unions, which grant all the benefits of marriage, have been recognized since 2014, and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is constitutionally banned. The General Council passed a bill on 21 July 2022 that would legalize same-sex marriage in 2023, and convert all civil unions into civil marriage. In September 2023, Xavier Espot Zamora, the Prime Minister of Andorra, officially came out as homosexual.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Monaco may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Monaco. However, same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Monaco is the least developed among Western European countries in terms of LGBT equality.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Switzerland are some of the most progressive by world standards. Social attitudes and the legal situation have liberalised at an increasing pace since the 1940s, in parallel to the situation in Europe and the Western world more generally. Legislation providing for same-sex marriage, same-sex adoption, and IVF access was accepted by 64% of voters in a referendum on 26 September 2021, and entered into force on 1 July 2022.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Argentina rank among the highest in the world. Upon legalising same-sex marriage on 15 July 2010, Argentina became the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth in the world to do so. Following Argentina's transition to a democracy in 1983, its laws have become more inclusive and accepting of LGBT people, as has public opinion.

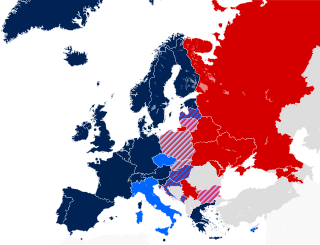

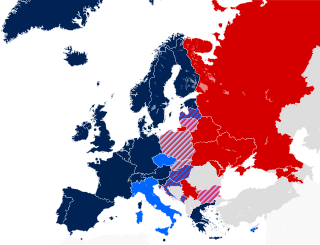

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Angola have seen improvements in the early 21st century. In November 2020, the National Assembly approved a new penal code, which legalised consenting same-sex sexual activity. Additionally, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned, making Angola one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBT people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Haiti face social and legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Adult, noncommercial and consensual same-sex sexuality is not a criminal offense, but transgender people can be fined for violating a broadly written vagrancy law. Public opinion tends to be opposed to LGBT rights, which is why LGBT people are not protected from discrimination, are not included in hate crime laws, and households headed by same-sex couples do not have any of the legal rights given to married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Ivory Coast face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal for both men and women in Ivory Coast, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Dominican Republic do not possess the same legal protections as non-LGBT residents, and face social challenges that are not experienced by other people. While the Dominican Criminal Code does not expressly prohibit same-sex sexual relations or cross-dressing, it also does not address discrimination or harassment on the account of sexual orientation or gender identity, nor does it recognize same-sex unions in any form, whether it be marriage or partnerships. Households headed by same-sex couples are also not eligible for any of the same rights given to opposite-sex married couples, as same-sex marriage is constitutionally banned in the country.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Bolivia have expanded significantly in the 21st century. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity and same-sex civil unions are legal in Bolivia. The Bolivian Constitution bans discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2016, Bolivia passed a comprehensive gender identity law, seen as one of the most progressive laws relating to transgender people in the world.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Mauritius have expanded in the 21st century, although LGBT Mauritians may still face legal difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Prior to 2023, sodomy was criminalized by Section 250 of the Criminal Code. However, Mauritius fully decriminalized homosexuality in October 2023. Although same-sex marriage is not recognized in Mauritius, LGBT people are broadly protected from discrimination in areas such as employment and the provision of goods and services, making it one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBT people. The Constitution of Mauritius guarantees the right of individuals to a private life.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Mozambique face legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT people. Same-sex sexual activity became legal in Mozambique under the new Criminal Code that took effect in June 2015. Discrimination based on sexual orientation in employment has been illegal since 2007.

Paris, the capital of France, has an active LGBT community. In the 1990s, 46% of the country's gay men lived in the city. As of 2004, Paris had 140 LGBT bars, clubs, hotels, restaurants, shops, and other commercial businesses. Florence Tamagne, author of "Paris: 'Resting on its Laurels'?", wrote that there is a "Gaité parisienne"; she added that Paris "competes with Berlin for the title of LGBT capital of Europe, and ranks only second behind New York for the title of LGBT capital of the world." It has France's only gayborhoods that are officially organized.

Jean Le Bitoux was a French journalist and gay activist. He was the founder of Gai pied, the first mainstream gay magazine in France. He was a campaigner for Holocaust remembrance of homosexual victims. He was the author of several books about homosexuality.

The following is a timeline of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) history in the 20th century.

Beit Haverim is a French organization for LGBT Jews.