This is a list of New Zealand species extinct in the Holocene that covers extinctions from the Holocene epoch, a geologic epoch that began about 11,650 years Before Present (about 9700 BCE) [a] and continues to the present day. [1] This epoch equates with the latter third of the Haweran Stage of the Wanganui epoch in the New Zealand geologic time scale.

Contents

- Mammals (class Mammalia)

- Bats (order Chiroptera)

- Carnivorans (order Carnivora)

- Birds (class Aves)

- Moa (order Dinornithiformes)

- Kiwis (order Apterygiformes)

- Landfowl (order Galliformes)

- Waterfowl (order Anseriformes)

- Owlet-nightjars (order Aegotheliformes)

- Pigeons and doves (order Columbiformes)

- Rails and cranes (order Gruiformes)

- Shorebirds (order Charadriiformes)

- Albatrosses and petrels (order Procellariiformes)

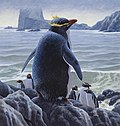

- Penguins (order Sphenisciformes)

- Boobies, cormorants, and allies (order Suliformes)

- Pelicans, herons, and ibises (order Pelecaniformes)

- Hawks and relatives (order Accipitriformes)

- Owls (order Strigiformes)

- Parrots (order Psittaciformes)

- Perching birds (order Passeriformes)

- Reptiles (class Reptilia)

- Squamates (order Squamata)[e]

- Amphibians (class Amphibia)

- Frogs (order Anura)

- Ray-finned fish (class Actinopterygii)

- Smelts (order Osmeriformes)

- Insects (class Insecta)

- Beetles (order Coleoptera)

- Bark lice, book lice, and parasitic lice (order Psocodea)

- Clitellates (class Clitellata)

- Order Opisthopora

- Plants (kingdom Plantae)

- Order Brassicales

- Order Santalales

- Order Caryophyllales

- Order Gentianales

- Order Boraginales

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

The North Island and South Island are the two largest islands of New Zealand. Stewart Island is the largest of the smaller islands. New Zealand proper also includes outlying islands such as the Chatham Islands, Kermadec Islands, and New Zealand Subantarctic Islands. Only New Zealand proper is represented on this list, not the Realm of New Zealand. For extinctions in the Cook Islands, Niue, or Tokelau, see the List of Oceanian animals extinct in the Holocene.

The islands of East Polynesia (including New Zealand, Hawaii, and Easter Island) were among the last habitable places on Earth colonised by humans. [2] [3] The first settlers of New Zealand migrated from Polynesia and became the Māori people. [4] According to archeological and genetic research, the ancestors of the Māori arrived in New Zealand no earlier than about 1280 CE, with at least the main settlement period between about 1320 and 1350, [5] [4] consistent with evidence based on whakapapa (genealogical traditions). [6] [7] No credible evidence exists of pre-Māori settlement of New Zealand. [4] In 1642, the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman became the first European explorer known to visit New Zealand. [8] In 1769, British explorer James Cook became the first European to map New Zealand and communicate with the Māori. [9] [10] From the late 18th century, the country was regularly visited by explorers and other sailors, missionaries, traders and adventurers. In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi annexed New Zealand into the British Empire. [11] [12] [13] As a result of the influx of settlers, the population of Pākehā (European New Zealanders) grew explosively from fewer than 1,000 in 1831 to 500,000 by 1881. [14]

Numerous species have disappeared from New Zealand as part of the ongoing Holocene extinction, driven by human activity. Human contact, first by Polynesians and later by Europeans, had a significant impact on the environment. The arrival of the Māori resulted in animal extinctions due to deforestation [3] and hunting. [15] The Māori also brought two species of land mammals, Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) and kurī, a breed of domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris). [3] [16] In pre-human times, bats were the only land mammals found in New Zealand. [17] Polynesian rats definitely contributed to extinctions, [3] and kurī might have contributed as well. [18] [19] Like the Māori settlers centuries earlier, the European settlers hunted native animals and engaged in habitat destruction. They also introduced numerous invasive species. [20] A few examples are black rats (Rattus rattus) and brown rats (Rattus norvegicus), [21] domestic cats (Felis catus), [22] stoats (Mustela erminea), [23] and common brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula). [24]

This list of extinct species only includes the indigenous biota of New Zealand, not domestic animals like the kurī.