Proboscidea is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three species of elephant are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant.

Catopsbaatar is a genus of multituberculate, an extinct order of rodent-like mammals. It lived in what is now Mongolia during the late Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous epoch, about 72 million years ago. The first fossils were collected in the early 1970s, and the animal was named as a new species of the genus Djadochtatherium in 1974, D. catopsaloides. The specific name refers to the animal's similarity to the genus Catopsalis. The species was moved to the genus Catopsalis in 1979, and received its own genus in 1994. Five skulls, one molar, and one skeleton with a skull are known; the last is the genus' most complete specimen. Catopsbaatar was a member of the family Djadochtatheriidae.

Moeritherium is an extinct genus of basal proboscideans from the Eocene of North and West Africa. It was related to elephants and, more distantly, to sea cows and hyraxes.

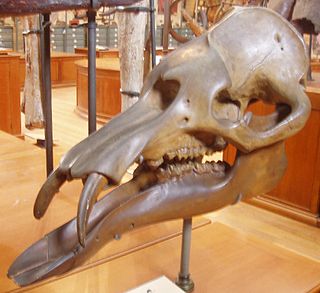

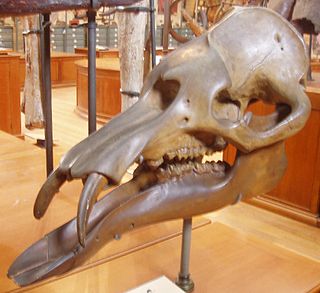

Deinotheriidae is a family of prehistoric elephant-like proboscideans that lived during the Cenozoic era, first appearing in Africa, then spreading across southern Asia (Indo-Pakistan) and Europe. During that time, they changed very little, apart from growing much larger in size; by the late Miocene, they had become the largest land animals of their time. Their most distinctive features were their lack of upper tusks and downward-curving tusks on the lower jaw.

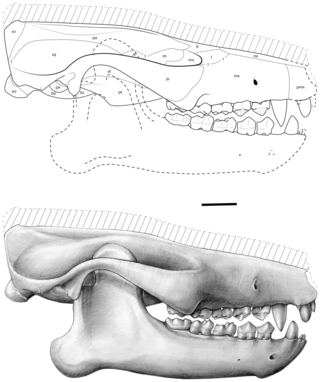

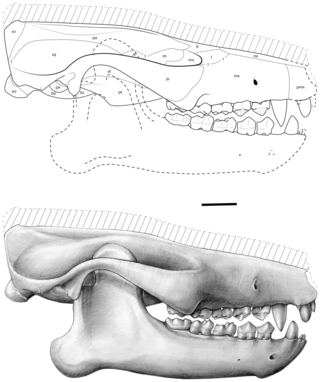

Prodeinotherium is an extinct representative of the family Deinotheriidae that lived in Africa, Europe, and Asia in the early and middle Miocene. Prodeinotherium, meaning "before terrible beast", was first named in 1930, but soon after, the only species in it, P. hungaricum, was reassigned to Deinotherium. During the 1970s, however, the two genera were once again separated, with Prodeinotherium diagnosed to include Deinotherium bavaricum, Deinotherium hobleyi, and Deinotherium pentapotamiae, which were separated based on geographic location. The three species are from Europe, Africa, and Asia, respectively. However, because of usage of few characters to separate them, only one species, P. bavaricum, or many more species, including P. cuvieri, P. orlovii, and P. sinense may be possible.

Paraceratherium is an extinct genus of hornless rhinocerotoids belonging to the family Paraceratheriidae. It is one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed and lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch. The first fossils were discovered in what is now Pakistan, and remains have been found across Eurasia between China and the Balkans. Paraceratherium means "near the hornless beast", in reference to Aceratherium, the genus in which the type species P. bugtiense was originally placed.

Pyrotherium is an extinct genus of South American ungulate, of the order Pyrotheria, that lived in what is now Argentina and Bolivia, during the Late Oligocene. It was named Pyrotherium because the first specimens were excavated from an ancient volcanic ash deposit. Fossils of the genus have been found in the Deseado and Sarmiento Formations of Argentina and the Salla Formation of Bolivia.

Numidotheriidae is an extinct family of primitive proboscideans that lived from the late Paleocene to the early Oligocene periods of North Africa.

Daouitherium is an extinct genus of early proboscideans that lived during the early Eocene some 55 million years ago in North Africa.

Phosphatherium escuillei is a basal proboscidean that lived from the Late Paleocene to the early stages of the Ypresian age. Research has suggested that Phosphatherium existed during the Eocene period.

Palaeomastodon is an extinct genus within the elephant order Proboscidea. Its fossils have been extracted from Oligocene strata conventionally dated to 33.9-23.03 million years old. Usually considered an ancestor or near-ancestor of elephants or mastodons as a member of Elephantiformes it lived in marshes and fluvial-deltaic environments of what is now Egypt, Ethiopia, Libya, and Saudi Arabia.

Notiomastodon is an extinct genus of gomphothere proboscidean, endemic to South America from the Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene. Notiomastodon specimens reached a size similar to that of the modern Asian elephant, with a body mass of 3-4 tonnes. Like other brevirostrine gomphotheres such as Cuvieronius and Stegomastodon, Notiomastodon had a shortened lower jaw and lacked lower tusks, unlike more primitive gomphotheres like Gomphotherium.

Eritherium is an extinct genus of early Proboscidea found in the Ouled Abdoun basin, Morocco. It lived about 60 million years ago. It was first named by Emmanuel Gheerbrant in 2009 and the type species is Eritherium azzouzorum. Eritherium is the oldest, smallest and most primitive known elephant relative.

Karenites is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids from the Late Permian of Russia. The only species is Karenites ornamentatus, named in 1995. Several fossil specimens are known from the town of Kotelnich in Kirov Oblast.

Homogalax is an extinct genus of tapir-like odd-toed ungulate. It was described on the basis of several fossil finds from the northwest of the United States, whereby the majority of the remains come from the state of Wyoming. The finds date to the Lower Eocene between 56 and 48 million years ago. In general, Homogalax was very small, only reaching the weight of today's peccaries, with a maximum of 15 kg. Phylogenetic analysis suggests the genus to be a basal member of the clade that includes today's rhinoceros and tapirs. In contrast to these, Homogalax was adapted to fast locomotion.

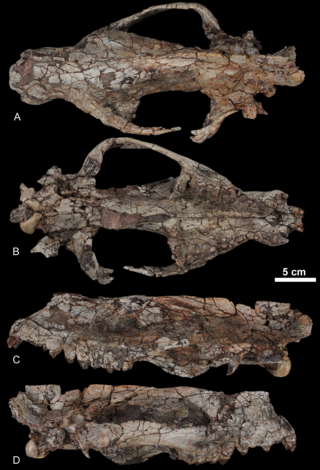

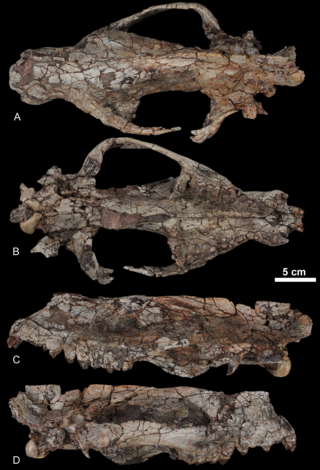

Ocepeia is an extinct genus of afrotherian mammal that lived in present-day Morocco during the middle Paleocene epoch, approximately 60 million years ago. First named and described in 2001, the type species is O. daouiensis from the Selandian stage of Morocco's Ouled Abdoun Basin. A second, larger species, O. grandis, is known from the Thanetian, a slightly younger stage in the same area. In life, the two species are estimated to have weighed about 3.5 kg (7.7 lb) and 10 kg (22 lb), respectively, and are believed to have been specialized leaf-eaters. The fossil skulls of Ocepeia are the oldest known afrotherian skulls, and the best-known of any Paleocene mammal in Africa.P

Elephantiformes is a suborder within the order Proboscidea. Members of this group are primitively characterised by the possession of upper tusks, an elongated mandibular symphysis and lower tusks, and the retraction of the facial region of the skull indicative of the development of a trunk. The earliest known member of the group, Dagbatitherium is known from the Eocene (Lutetian) of Togo, which is only known from isolated teeth, while other primitive elephantiforms like Phiomia and Palaeomastodon are known from the Early Oligocene onwards. Phiomia and Palaeomastodon are often collectively referred to as "palaeomastodonts" and assigned to the family Palaeomastodontidae. Most diversity of the group is placed in the subclade Elephantimorpha, which includes mastodons, as well as modern elephants and gomphotheres (Elephantida). It is disputed as to whether Phiomia is closely related to both Mammutidae and Elephantida with Palaeomastodon being more basal, or if Palaeomastodon is closely related to Mammutidae and Phiomia more closely related to Elephantida.

Arcanotherium is an extinct genus of early proboscidean belonging to the family Numidotheriidae that lived in north Africa during the late Eocene/early Oligocene interval.

Kerberos ("Cerberus") is an extinct genus of hyainailourid hyaenodonts in the subfamily Hyainailourinae, that lived in Europe. It contains the single species Kerberos langebadreae.

Periptychus is an extinct genus of mammal belonging to the family Periptychidae. It lived from the Early to Late Paleocene and its fossil remains have been found in North America.