Jacopo Peri was an Italian composer, singer and instrumentalist of the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods. He wrote what is considered the first opera, the mostly lost Dafne, and also the earliest extant opera, Euridice (1600).

Cristofano Malvezzi was an Italian organist and composer of the late Renaissance. He was one of the most famous composers in the city of Florence during a time of transition to the Baroque style.

A madrigal is a form of secular vocal music most typical of the Renaissance and early Baroque (1600–1750) periods, although revisited by some later European composers. The polyphonic madrigal is unaccompanied, and the number of voices varies from two to eight, but the form usually features three to six voices, whilst the metre of the madrigal varies between two or three tercets, followed by one or two couplets. Unlike verse-repeating strophic forms sung to the same music, most madrigals are through-composed, featuring different music for each stanza of lyrics, whereby the composer expresses the emotions contained in each line and in single words of the poem being sung.

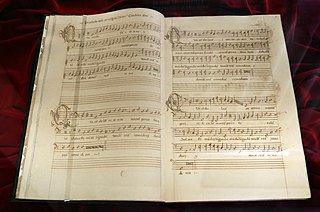

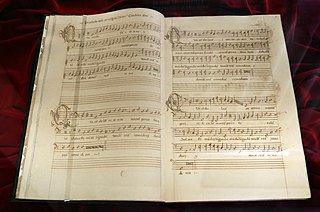

L'Orfeo, or La favola d'Orfeo, is a late Renaissance/early Baroque favola in musica, or opera, by Claudio Monteverdi, with a libretto by Alessandro Striggio. It is based on the Greek legend of Orpheus, and tells the story of his descent to Hades and his fruitless attempt to bring his dead bride Eurydice back to the living world. It was written in 1607 for a court performance during the annual Carnival at Mantua. While Jacopo Peri's Dafne is generally recognised as the first work in the opera genre, and the earliest surviving opera is Peri's Euridice, L'Orfeo is the earliest that is still regularly performed.

Dafne is the earliest known work that, by modern standards, could be considered an opera. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini, based on an earlier intermedio created in 1589, "Combattimento di Apollo col serpente Pitone," and set to music by Luca Marenzio, survives complete. The opera is considered to be the first "modern music drama."

The Florentine Camerata, also known as the Camerata de' Bardi, were a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de' Bardi to discuss and guide trends in the arts, especially music and drama. They met at the house of Giovanni de' Bardi, and their gatherings had the reputation of having all the most famous men of Florence as frequent guests. After first meeting in 1573, the activity of the Camerata reached its height between 1577 and 1582. While propounding a revival of the Greek dramatic style, the Camerata's musical experiments led to the development of the stile recitativo. In this way it facilitated the composition of dramatic music and the development of opera.

The intermedio, in the Italian Renaissance, was a theatrical performance or spectacle with music and often dance, which was performed between the acts of a play to celebrate special occasions in Italian courts. It was one of the important precursors to opera, and an influence on other forms like the English court masque. Weddings in ruling families and similar state occasions were the usual occasion for the most lavish intermedi, in cities such as Florence and Ferrara. Some of the best documentation of intermedi comes from weddings of the House of Medici, in particular the 1589 Medici wedding, which featured what was undoubtedly both the most spectacular set of intermedi, and the best known, thanks to no fewer than 18 contemporary published festival books and sets of prints that were financed by the Grand Duke.

Emilio de' Cavalieri, or Emilio dei Cavalieri, was an Italian composer, producer, organist, diplomat, choreographer and dancer at the end of the Renaissance era. His work, along with that of other composers active in Rome, Florence and Venice, was critical in defining the beginning of the musical Baroque era. A member of the Roman School of composers, he was an influential early composer of monody, and wrote what is usually considered to be the first oratorio.

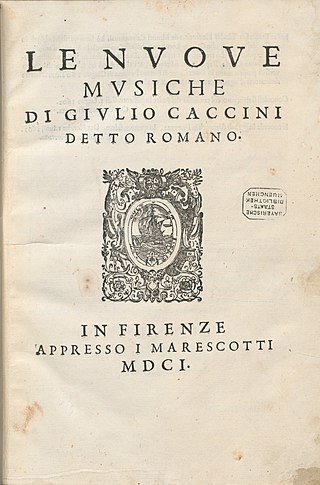

Giulio Romolo Caccini was an Italian composer, teacher, singer, instrumentalist and writer of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. He was one of the founders of the genre of opera, and one of the most influential creators of the new Baroque style. He was also the father of the composer Francesca Caccini and the singer Settimia Caccini.

Marco da Gagliano was an Italian composer of the early Baroque era. He was important in the early history of opera and the development of the solo and concerted madrigal.

Ottavio Rinuccini was an Italian poet, courtier, and opera librettist at the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. In collaborating with Jacopo Peri to produce the first opera, Dafne, in 1597, he became the first opera librettist.

Italian opera is both the art of opera in Italy and opera in the Italian language. Opera was in Italy around the year 1600 and Italian opera has continued to play a dominant role in the history of the form until the present day. Many famous operas in Italian were written by foreign composers, including Handel, Gluck and Mozart. Works by native Italian composers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Verdi and Puccini, are amongst the most famous operas ever written and today are performed in opera houses across the world.

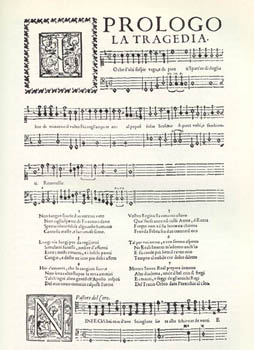

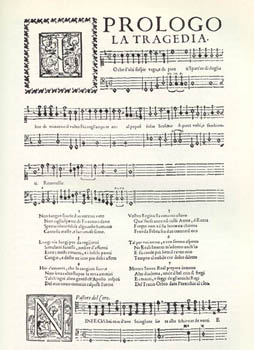

Euridice is an opera by Jacopo Peri, with additional music by Giulio Caccini. It is the earliest surviving opera, Peri's earlier Dafne being lost. The libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini is based on books X and XI of Ovid's Metamorphoses which recount the story of the legendary musician Orpheus and his wife Euridice.

Rappresentatione di anima et di corpo is a musical work by Emilio de' Cavalieri to a libretto by Agostino Manni (1548–1618). With it, Cavalieri regarded himself as the composer of the first opera or oratorio. Whether he was actually the first is subject to some academic debate, as is whether the work is better categorized as an opera or an oratorio. It was first performed in Rome in February 1600 in the Oratorio dei Filippini adjacent to the church of Santa Maria in Vallicella.

L'Arianna is the lost second opera by Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi. One of the earliest operas in general, it was composed in 1607–1608 and first performed on 28 May 1608, as part of the musical festivities for a royal wedding at the court of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua. All the music is lost apart from the extended recitative known as "Lamento d'Arianna". The libretto, which survives complete, was written in eight scenes by Ottavio Rinuccini, who used Ovid's Heroides and other classical sources to relate the story of Ariadne's abandonment by Theseus on the island of Naxos and her subsequent elevation as bride to the god Bacchus.

Francesco Corteccia was an Italian composer, organist, and teacher of the Renaissance. Not only was he one of the best known of the early composers of madrigals, and an important native Italian composer during a period of domination by composers from the Low Countries, but he was the most prominent musician in Florence for several decades during the reign of Cosimo I de' Medici.

The Italian composer Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), in addition to a large output of church music and madrigals, wrote prolifically for the stage. His theatrical works were written between 1604 and 1643 and included operas, of which three—L'Orfeo (1607), Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (1640) and L'incoronazione di Poppea (1643)—have survived with their music and librettos intact. In the case of the other seven operas, the music has disappeared almost entirely, although some of the librettos exist. The loss of these works, written during a critical period of early opera history, has been much regretted by commentators and musicologists.

Die Dafne (1627) is an opera. Its libretto was written by Martin Opitz and its music was composed by Heinrich Schütz. It has traditionally been regarded as the first German opera, though it has also been proposed more recently that it was in fact a spoken drama with inserted song and ballet numbers.