Insects in the family Tettigoniidae are commonly called katydids, or bush crickets. They have previously been known as "long-horned grasshoppers". More than 8,000 species are known. Part of the suborder Ensifera, the Tettigoniidae are the only extant (living) family in the superfamily Tettigonioidea.

Ensifera is a suborder of insects that includes the various types of crickets and their allies including: true crickets, camel crickets, bush crickets or katydids, grigs, weta and Cooloola monsters. This and the suborder Caelifera make up the order Orthoptera. Ensifera is believed to be a more ancient group than Caelifera, with its origins in the Carboniferous period, the split having occurred at the end of the Permian period. Unlike the Caelifera, the Ensifera contain numerous members that are partially carnivorous, feeding on other insects, as well as plants.

Megacrania batesii, commonly known as the peppermint stick insect, is an unusual species of stick insect found in northeastern Australia, the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, and possibly as far north as the Philippines. It is notable for its aposematic coloration, as well as its robust chemical defense mechanism. Its common name refers to the irritating fluid — with an odor resembling peppermint — that it sprays as a defensive action from a pair of glands located at its prothorax when threatened, as well as the cylindrical, twig-like shape of its body. A member of the subfamily Megacraniinae, it was first described by English naturalist and explorer Henry Walter Bates in 1865.

Deinacrida fallai or the Poor Knights giant wētā is a species of insect in the family Anostostomatidae. It is endemic to the Poor Knights Islands off northern New Zealand. D. fallai are commonly called giant wētā due to their large size. They are one of the largest insects in the world, with a body length measuring up to 73 mm. Their size is an example of island gigantism. They are classified as vulnerable by the IUCN due to their restricted distribution.

Deinacrida heteracantha, also known as the Little Barrier giant wētā or wētāpunga, is a wētā in the order Orthoptera and family Anostostomatidae. It is endemic to New Zealand, where it survived only on Little Barrier Island, although it has been translocated to some other predator-free island conservation areas. This very large flightless wētā mainly feeds at night, but is also active during the day, when it can be found above ground in vegetation. It has been classified as vulnerable by the IUCN due to ongoing population declines and restricted distribution.

Deinacrida parva is a species of insect in the family Anostostomatidae, the king crickets and weta. It is known commonly as the Kaikoura wētā or Kaikoura giant wētā. It was first described in 1894 from a male individual then rediscovered in 1966 by Dr J.C. Watt at Lake Sedgemore in Upper Wairau. It is endemic to New Zealand, where it can be found in the northern half of the South Island.

There are many insects in the family Tettigoniidae which are mimics of leaves.

Acanthoplus discoidalis is a species in the Hetrodinae, a subfamily of the katydid family (Tettigoniidae). Like its closest relatives, Acanthoplus discoidalis variously bears common names such as armoured katydid, armoured ground cricket, armoured bush cricket, corn cricket, setotojane and koringkriek. The species is native to parts of Angola, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Phaneroptera nana, common name southern sickle bush-cricket, is a species in the family Tettigoniidae and subfamily Phaneropterinae. It has become an invasive species in California where it may be called the Mediterranean katydid.

Sathrophyllia is a genus of Asian bush crickets or katydids in the subfamily Pseudophyllinae and tribe Cymatomerini. They are usually found on the branches of bushes or trees where they sit close to a branch and spread out their forelegs and antennae along the branch and hold themselves close to the surface with their middle pair of legs. Some species like S. rugosa have cryptic colouration that matches the bark making them very hard to spot. Further east, the genus Olcinia also bears a close resemblance, however Sathrophyllia has a relatively smooth margin to the forewing unlike that of Olcinia.

The Copiphorini are a tribe of bush crickets or katydids in the family Tettigoniidae. Previously considered a subfamily, they are now placed in the subfamily Conocephalinae. Like some other members of Conocephalinae, they are known as coneheads, grasshopper-like insects with an extended, cone-shaped projection on their heads that juts forward in front of the base of the antennae.

Conocephalinae, meaning "conical head", is an Orthopteran subfamily in the family Tettigoniidae.

Pterinoxylus spinulosus is a species of stick insect found in the Neotropics. It was first described by the Austrian entomologist Ludwig Redtenbacher in 1908, from an adult male and an immature female. It was not until 1957 that an adult female was described by J.A.G. Rehn.

Capnobotes fuliginosus is a species of katydid known as the sooty longwing. It is found in the western United States and Mexico. It is omnivorous and it is the prey of the wasp Palmodes praestans.

Cyphoderris monstrosa, also known as the great grig, is a species of hump-winged grig in the family Prophalangopsidae. Though the fossil record shows at least 90 extinct species from this family, C. monstrosa is one of only 7 known species alive today.

Chlorobalius is a species of long-horned grasshopper in the family Tettigoniidae containing the only species, Chlorobalius leucoviridis, commonly known as the spotted predatory katydid. It is a predator and is an acoustic aggressive mimic of cicadas; by imitating the sounds and movements made by female cicadas, it lures male cicadas to within its reach and then eats them.

Caedicia simplex is a species of bush cricket, native to New Zealand. It is also found in Australia. Its common name is the common garden katydid.

Erechthis levyi, the blue-faced katydid or Eleuthera rhino katydid, is a katydid found in The Bahamas. Currently, it is described from specimens collected only on the island of Eleuthera. They are light brown in color throughout the body, but exhibit a bright turquoise-blue face and bear a prominent spine on the vertex of the head between the eyes, hence the common names. It is tentatively considered an endemic species to The Bahamas, as no specimens are recorded from Cuba or Hispaniola, where other Erechthis species occur. The species was named in honor of Leon Levy, a prominent Wall Street financier and philanthropist who spent much time on Eleuthera and was an avid admirer of the island's flora and natural beauty.

Erechthis is a genus of Caribbean katydids in the tribe Agraeciini. They are distributed across a few islands in the Greater Antilles region.

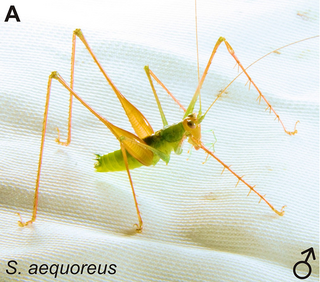

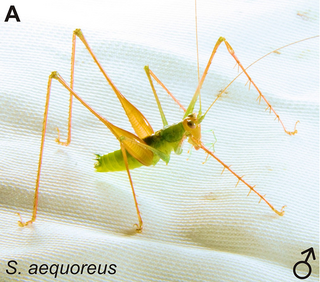

Supersonus is a genus of katydids in the order Orthoptera first described in 2014. The genus contains three species which are endemic to the rainforests of South America. Its name is an allusion to the fact that the males, in order to attract the females, produce a very high frequency noise which can reach 150 kHz. This has been considered the highest frequency ultrasonic noise of the animal kingdom. The noise is imperceptible to human hearing, which is only capable of detecting up to 20 kHz.