| Penjikent murals | |

|---|---|

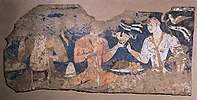

Penjikent mural in the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg. | |

| Created | 5th century - 722 CE |

| Discovered | Panjakent, Tajikistan 39°29′12″N67°37′14″E / 39.486792°N 67.620477°E |

| Present location | Hermitage Museum, National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan |

| Culture | Sogdian |

The murals of Penjikent are among the most famous murals of the pre-Islamic period in Panjakent, ancient Sogdiana, in Tajikistan. Numerous murals were recovered from the site, and many of them are now on display in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, and in the National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan in Dushanbe. The murals reveal the cosmopolitan nature of the Penjikent society that was mainly composed of Sogdian and Turkic elites and likely other foreign merchant groups of heterogeneous origin. [1] Significant similarities with Old Turkic clothing, weaponry, hairstyles and ritual cups are noted by comparative research. [2]

Contents

- Rulers

- Festivities

- Rostam cycle

- Details

- Religion

- Battle scenes

- Female figures

- Ethnicities

- See also

- References

The murals of Penjikent are the earliest known Sogdian murals, starting from the late 5th to early 6th century CE, and are preceded by the Hepthalite murals of Tukharistan as seen in Balalyk Tepe, from which they received iconographical and stylistic influence. [3] Also visible is a great variety of Hellenistic influences of Greek decorative styles along with local Zoroastrian, Christian, Buddhist and Indic cults.[ citation needed ]

The production of paintings started in the end of the 5th century CE and stopped in 722 CE with the invasion of the Abbasid Caliphate, in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana, and many works of art were damaged or destroyed at that time. [4] [5] [6]