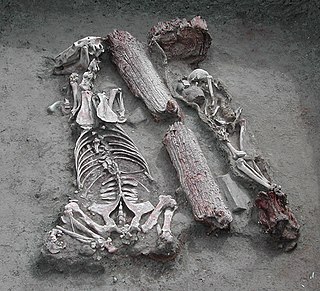

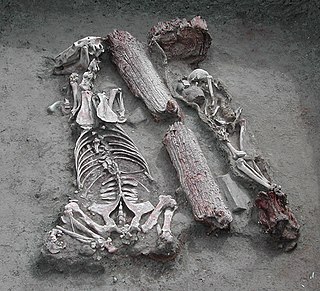

The Pazyrykburials are a number of Scythian (Saka) Iron Age tombs found in the Pazyryk Valley and the Ukok plateau in the Altai Mountains, Siberia, south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, Russia; the site is close to the borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

The Saka were a group of nomadic Eastern Iranian peoples who historically inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.

The Pazyryk culture is a Saka nomadic Iron Age archaeological culture identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans found in the Siberian permafrost, in the Altay Mountains, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. The mummies are buried in long barrows similar to the tomb mounds of Scythian culture in Ukraine. The type site are the Pazyryk burials of the Ukok Plateau. Many artifacts and human remains have been found at this location, including the Siberian Ice Princess, indicating a flourishing culture at this location that benefited from the many trade routes and caravans of merchants passing through the area. The Pazyryk are considered to have had a war-like life. The Pazyryk culture was preceded by the "Arzhan culture".

Scytho-Siberian art is the art associated with the cultures of the Scytho-Siberian world, primarily consisting of decorative objects such as jewellery, produced by the nomadic tribes of the Eurasian Steppe, with the western edges of the region vaguely defined by ancient Greeks. The identities of the nomadic peoples of the steppes is often uncertain, and the term "Scythian" should often be taken loosely; the art of nomads much further east than the core Scythian territory exhibits close similarities as well as differences, and terms such as the "Scytho-Siberian world" are often used. Other Eurasian nomad peoples recognised by ancient writers, notably Herodotus, include the Massagetae, Sarmatians, and Saka, the last a name from Persian sources, while ancient Chinese sources speak of the Xiongnu or Hsiung-nu. Modern archaeologists recognise, among others, the Pazyryk, Tagar, and Aldy-Bel cultures, with the furthest east of all, the later Ordos culture a little west of Beijing. The art of these peoples is collectively known as steppes art.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe, who are largely known from frontier historical sources from Europe and Asia.

The Ordos culture was a material culture occupying a region centered on the Ordos Loop during the Bronze and early Iron Age from c. 800 BCE to 150 BCE. The Ordos culture is known for significant finds of Scythian art and may represent the easternmost extension of Indo-European Eurasian nomads, such as the Saka, or may be linkable to Palaeo-Siberians or Yeniseians. Under the Qin and Han dynasties, the area came under the control of contemporaneous Chinese states.

The Tagar culture was a Bronze Age Saka archeological culture which flourished between the 8th and 1st centuries BC in South Siberia. The culture was named after an island in the Yenisei River opposite Minusinsk. The civilization was one of the largest centres of bronze-smelting in ancient Eurasia.

The Orlat plaques are a series of bone plaques that were discovered in the mid-1980s in Uzbekistan. They were found during excavations led by Galina Pugachenkova at the cemetery of Orlat, by the bank of the Saganak River, immediately north of Samarkand. Pugachenkova published her finds in 1989. The left half is decorated with an elaborated battle scene, while on the other side is depicted a hunting scene.

Arzhan is a site of early Saka kurgan burials in the Tuva Republic, Russia, some 60 kilometers (40 mi) northwest of Kyzyl. It is on a high plateau traversed by the Uyuk River, a minor tributary of the Yenisei River, in the region of Tuva, 20 km to the southwest of the city of Turan.

Takht-i Sangin is an archaeological site located near the confluence of the Vakhsh and Panj rivers, the source of the Amu Darya, in southern Tajikistan. During the Hellenistic period it was a city in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom with a large temple dedicated to the Oxus, which remained in use in the following Kushan period, until the third century AD. The site may have been the source of the Oxus Treasure.

The Scytho-Siberian world was an archaeological horizon that flourished across the entire Eurasian Steppe during the Iron Age, from approximately the 9th century BC to the 2nd century AD. It included the Scythian, Sauromatian and Sarmatian cultures of Eastern Europe, the Saka-Massagetae and Tasmola cultures of Central Asia, and the Aldy-Bel, Pazyryk and Tagar cultures of south Siberia.

Berel kurgan is an archaeological site in the Katonkaragay District in eastern Kazakhstan. The site is located near the village of Berel. At this site, numerous 5th-3rd century BCE Early Saka kurgans were found.

Sargatka culture, was a sedentary archaeological culture that existed between 7th century BC and 5th century AD in Western Siberia. Sargatka cultural horizon encompassed northern forest steppe zone between the Tobol and Irtysh rivers, which is currently located in Russia and Kazakhstan. The northernmost Sargatka culture presence is found near Tobolsk, on the border of the forest zone. In the south, the area of culture coincides with the southern border of the forest-steppe. Eastern foothills of the Urals make up the western boundary of the culture, meanwhile Baraba forest-steppe forms the eastern edge for Sargatka settlements and burial grounds. The culture is named after the village of Sargatskoye on the Sargatka River, which is located near a Sargatka burial ground.

The names of the Scythians are a topic of interest for classicists and linguists. The Scythians were an Iranic people best known for dominating much of the Pontic steppe from about 700 BC to 400 BC. The name of the Scythians is believed to be of Indo-European origin and to have meant "archer". The Scythians gave their name to the region of Scythia. The Persians referred to all Iranic nomads of the steppes, including the Scythians, as Sakas. Some modern scholars apply the name Scythians to all peoples of the Scytho-Siberian world, but this terminology is controversial.

The Ai-Khanoum plaque is an ancient Greco-Bactrian disk discovered at the archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. This Hellenistic city served as a military and economic center for the rulers of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until its destruction c. 145 BC. Rediscovered in 1961, the ruins of the city were excavated by the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) until an outbreak of conflict in Afghanistan during the late 1970s. Among the structures excavated by the archaeologists was a sanctuary called the 'Temple of Indented Niches', in which the disk was found. The disk is held in the collection of the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

The Saksanokhur gold buckle is an ancient belt buckle in gold repoussé, discovered in the Hellenistic archaeological site of Saksanokhur, South Tajikistan. The plate represents a nomadic horserider spearing a boar, set within a rectangular decorative frame. The buckle is generally dated to the 1st-2nd century CE, although Francfort dates it earlier to the 2nd-1st century BCE, as do the curators for the Guimet Museum, and the National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan.

The Taksai kurgans are a series of Saka or Sauromatian funeral mounds or kurgans, located in the Terekti District of the southern Urals, in northwestern Kazakhstan. They are dated to circa 500 BCE. The Kurgan was undisturbed and had provided numerous valuable artifacts. The Taksai-1 kurgan was the tomb of a rich Saka lady, dubbed the "golden lady". Some of her objects reflect the iconography of the Achaemenid Empire, which must have been in contact with these nomadic tribes.

The Siberian Collection of Peter the Great is a series of Saka Animal art gold artifacts that were discovered in Southern Siberia, from funeral kurgan tumuli, in mostly unrecorded locations in the area between modern Kazakhstan and the Altai Mountains. The objects are generally dated to the 6th to the 1st centuries BCE.

The Filippovka kurgans are Late-Sauromatian to Early-Sarmatian culture kurgans, forming "a transition site between the Sauromation and the Sarmatian epochs", just north of the Caspian Sea in the Orenburg region of Russia, dated to the second half of the 5th century and the 4th century BCE.

The Maoqinggou culture is an archaeological culture of Inner Mongolia, to the east of the Ordos culture area, centered around the Maoqinggou cemetery. It is an important site for the understanding of China's northern grasslands in the early Iron Age. The site has four phases, from the Spring and Autumn period to the late Warring States period, including a period of early Xiongnu occupation.