Catatonia is a complex neuropsychiatric behavioral syndrome that is characterized by abnormal movements, immobility, abnormal behaviors, and withdrawal. The onset of catatonia can be acute or subtle and symptoms can wax, wane, or change during episodes. It has historically been related to schizophrenia, but catatonia is most often seen in mood disorders. It is now known that catatonic symptoms are nonspecific and may be observed in other mental, neurological, and medical conditions. Catatonia is now a stand-alone diagnosis, and the term is used to describe a feature of the underlying disorder.

Central pontine myelinolysis is a neurological condition involving severe damage to the myelin sheath of nerve cells in the pons. It is predominately iatrogenic (treatment-induced), and is characterized by acute paralysis, dysphagia, dysarthria, and other neurological symptoms.

Diabetes insipidus (DI), alternately called arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D) or arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R), is a condition characterized by large amounts of dilute urine and increased thirst. The amount of urine produced can be nearly 20 liters per day. Reduction of fluid has little effect on the concentration of the urine. Complications may include dehydration or seizures.

Hyponatremia or hyponatraemia is a low concentration of sodium in the blood. It is generally defined as a sodium concentration of less than 135 mmol/L (135 mEq/L), with severe hyponatremia being below 120 mEq/L. Symptoms can be absent, mild or severe. Mild symptoms include a decreased ability to think, headaches, nausea, and poor balance. Severe symptoms include confusion, seizures, and coma; death can ensue.

Polyuria is excessive or an abnormally large production or passage of urine. Increased production and passage of urine may also be termed as diuresis. Polyuria often appears in conjunction with polydipsia, though it is possible to have one without the other, and the latter may be a cause or an effect. Primary polydipsia may lead to polyuria. Polyuria is usually viewed as a symptom or sign of another disorder, but it can be classed as a disorder, at least when its underlying causes are not clear.

Polydipsia is excessive thirst or excess drinking. The word derives from the Greek πολυδίψιος (poludípsios) "very thirsty", which is derived from πολύς + δίψα. Polydipsia is a nonspecific symptom in various medical disorders. It also occurs as an abnormal behaviour in some non-human animals, such as in birds.

Electrolyte imbalance, or water-electrolyte imbalance, is an abnormality in the concentration of electrolytes in the body. Electrolytes play a vital role in maintaining homeostasis in the body. They help to regulate heart and neurological function, fluid balance, oxygen delivery, acid–base balance and much more. Electrolyte imbalances can develop by consuming too little or too much electrolyte as well as excreting too little or too much electrolyte. Examples of electrolytes include calcium, chloride, magnesium, phosphate, potassium, and sodium.

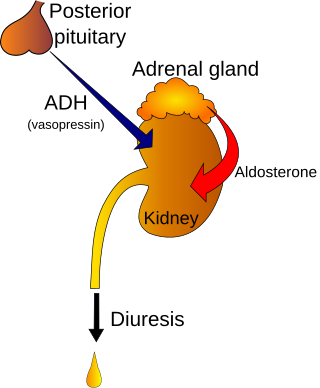

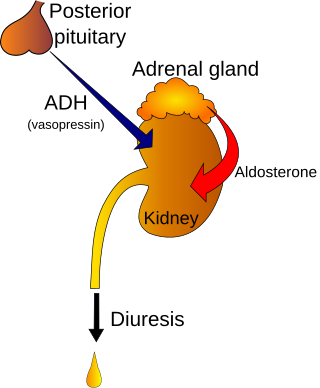

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), also known as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD), is characterized by a physiologically inappropriate release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) either from the posterior pituitary gland, or an abnormal non-pituitary source. Unsuppressed ADH causes a physiologically inappropriate increase in solute-free water being reabsorbed by the tubules of the kidney to the venous circulation leading to hypotonic hyponatremia.

Water intoxication, also known as water poisoning, hyperhydration, overhydration or water toxemia is a potentially fatal disturbance in brain functions that can result when the normal balance of electrolytes in the body is pushed outside safe limits by excessive water intake.

Conivaptan, sold under the brand name Vaprisol, is a non-peptide inhibitor of the receptor for anti-diuretic hormone, also called vasopressin. It was approved in 2004 for hyponatremia. The compound was discovered by Astellas and marked in 2006. The drug is now marketed by Cumberland Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Cerebral salt-wasting syndrome (CSWS), also written cerebral salt wasting syndrome, is a rare endocrine condition featuring a low blood sodium concentration and dehydration in response to injury (trauma) or the presence of tumors in or surrounding the brain. In this condition, the kidney is functioning normally but excreting excessive sodium. The condition was initially described in 1950. Its cause and management remain controversial. In the current literature across several fields, including neurology, neurosurgery, nephrology, and critical care medicine, there is controversy over whether CSWS is a distinct condition, or a special form of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH).

Demeclocycline is a tetracycline antibiotic which was derived from a mutant strain of Streptomyces aureofaciens.

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES), also referred to as non-epileptic attacks (NEA), functional seizures, or dissociative seizures, are episodes resembling an epileptic seizure but without the characteristic electrical discharges associated with epilepsy. PNES fall under the category of disorders known as functional neurological disorders (FND), also known as conversion disorders, and are typically treated by psychologists or psychiatrists. PNES has previously been called pseudoseizures, stress seizures, and hysterical seizures, but these terms have fallen out of favor.

Nocturia is defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as "the complaint that the individual has to wake at night one or more times for voiding ". The term is derived from Latin nox – "night", and Greek [τα] ούρα – "urine". Causes are varied and can be difficult to discern. Although not every patient needs treatment, most people seek treatment for severe nocturia, waking up to void more than 2 or 3 times per night.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, recently renamed as arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R) and also previously known as renal diabetes insipidus, is a form of diabetes insipidus primarily due to pathology of the kidney. This is in contrast to central or neurogenic diabetes insipidus, which is caused by insufficient levels of vasopressin. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is caused by an improper response of the kidney to vasopressin, leading to a decrease in the ability of the kidney to concentrate the urine by removing free water.

Aquaporin-2 (AQP-2) is found in the apical cell membranes of the kidney's collecting duct principal cells and in intracellular vesicles located throughout the cell. It is encoded by the AQP2 gene.

A fluid or water deprivation test is a medical test which can be used to determine whether the patient has diabetes insipidus as opposed to other causes of polydipsia. The patient is required, for a prolonged period, to forgo intake of water completely, to determine the cause of the thirst.

Psychogenic pain is physical pain that is caused, increased, or prolonged by mental, emotional, or behavioral factors, without evidence of physical injury or illness.

Central diabetes insipidus, recently renamed arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D), is a form of diabetes insipidus that is due to a lack of vasopressin (ADH) production in the brain. Vasopressin acts to increase the volume of blood (intravascularly), and decrease the volume of urine produced. Therefore, a lack of it causes increased urine production and volume depletion.

Adipsia, also known as hypodipsia, is a symptom of inappropriately decreased or absent feelings of thirst. It involves an increased osmolality or concentration of solute in the urine, which stimulates secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the hypothalamus to the kidneys. This causes the person to retain water and ultimately become unable to feel thirst. Due to its rarity, the disorder has not been the subject of many research studies.