Dimetrodon is a genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Cisuralian age of the Early Permian period, around 295–272 million years ago. It is a member of the family Sphenacodontidae. With most species measuring 1.7–4.6 m (5.6–15.1 ft) long and weighing 28–250 kg (62–551 lb), the most prominent feature of Dimetrodon is the large neural spine sail on its back formed by elongated spines extending from the vertebrae. It was an obligate quadruped and had a tall, curved skull with large teeth of different sizes set along the jaws. Most fossils have been found in the Southwestern United States, the majority of these coming from a geological deposit called the Red Beds of Texas and Oklahoma. More recently, its fossils have also been found in Germany and over a dozen species have been named since the genus was first erected in 1878.

Pelycosaur is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile had been used, and pelycosaur was considered an order, but this is now thought to be incorrect, and seen as outdated.

Edaphosaurus is a genus of extinct edaphosaurid synapsids that lived in what is now North America and Europe around 303.4 to 272.5 million years ago, during the Late Carboniferous to Early Permian. American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope first described Edaphosaurus in 1882, naming it for the "dental pavement" on both the upper and lower jaws, from the Greek edaphos έδαφος and σαῦρος ("lizard").

Sphenacodontidae is an extinct family of sphenacodontoid synapsids. Small to large, advanced, carnivorous, Late Pennsylvanian to middle Permian "pelycosaurs". The most recent one, Dimetrodon angelensis, is from the latest Kungurian or, more likely, early Roadian San Angelo Formation. However, given the notorious incompleteness of the fossil record, a recent study concluded that the Sphenacodontidae may have become extinct as recently as the early Capitanian. Primitive forms were generally small, but during the later part of the early Permian these animals grew progressively larger, to become the top predators of terrestrial environments. Sphenacodontid fossils are so far known only from North America and Europe.

Eupelycosauria is a large clade of animals characterized by the unique shape of their skull, encompassing all mammals and their closest extinct relatives. They first appeared 308 million years ago during the Early Pennsylvanian epoch, with the fossils of Echinerpeton and perhaps an even earlier genus, Protoclepsydrops, representing just one of the many stages in the evolution of mammals, in contrast to their earlier amniote ancestors.

Dimetrodon borealis, formerly known as Bathygnathus borealis, is an extinct species of pelycosaur-grade synapsid that lived about 270 million years ago (Ma) in the Early Middle Permian. A partial maxilla or upper jaw bone from Prince Edward Island in Canada is the only known fossil of Bathygnathus. The maxilla was discovered around 1845 during the course of a well excavation in Spring Brook in the New London area and its significance was recognized by geologists John William Dawson and Joseph Leidy. It was originally described by Leidy in 1854 as the lower jaw of a dinosaur, making it the first purported dinosaur to have been found in Canada, and the second to have been found in all of North America. The bone was later identified as that of a pelycosaur. Although its current classification as a sphenacodontid synapsid was not recognized until after the discovery of its more famous relative Dimetrodon in the 1870s, Bathygnathus is notable for being the first discovered sphenacodontid. A 2015 study by the researchers from the University of Toronto Mississauga, Carleton University and the Royal Ontario Museum reclassified the species into the genus Dimetrodon.

Varanopidae is an extinct family of amniotes that resembled monitor lizards and may have filled a similar niche, hence the name. Typically, they are considered synapsids that evolved from an Archaeothyris-like synapsid in the Late Carboniferous. However, some recent studies have recovered them being taxonomically closer to diapsid reptiles. A varanopid from the latest Middle Permian Pristerognathus Assemblage Zone is the youngest known varanopid and the last member of the "pelycosaur" group of synapsids.

Eothyrididae is an extinct family of very primitive, insectivorous synapsids. Only three genera are known, Eothyris, Vaughnictis and Oedaleops, all from the early Permian of North America. Their main distinguishing feature is the large caniniform tooth in front of the maxilla.

Sphenacodontoidea is a node-based clade that is defined to include the most recent common ancestor of Sphenacodontidae and Therapsida and its descendants. Sphenacodontoids are characterised by a number of synapomorphies concerning proportions of the bones of the skull and the teeth.

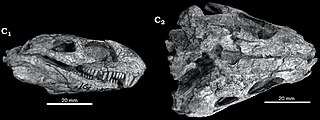

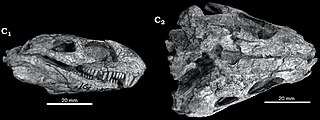

Ophiacodon is an extinct genus of synapsid belonging to the family Ophiacodontidae that lived from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian in North America and Europe. The genus was named along with its type species O. mirus by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878 and currently includes five other species. As an ophiacodontid, Ophiacodon is one of the most basal synapsids and is close to the evolutionary line leading to mammals.

Ctenospondylus is an extinct genus of sphenacodontid synapsid

Sphenacodon is an extinct genus of synapsid that lived from about 300 to about 280 million years ago (Ma) during the Late Carboniferous and Early Permian periods. Like the closely related Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon was a carnivorous member of the Eupelycosauria family Sphenacodontidae. However, Sphenacodon had a low crest along its back, formed from blade-like bones on its vertebrae instead of the tall dorsal sail found in Dimetrodon. Fossils of Sphenacodon are known from New Mexico and the Utah–Arizona border region in North America.

Mycterosaurus is an extinct genus of synapsids belonging to the family Varanopidae. It is classified in the varanopid subfamily Mycterosaurinae. Mycterosaurus is the most primitive member of its family, existing from 290.1 to 272.5 MYA, known to Texas and Oklahoma. It lacks some features that its advanced relatives have.

Eothyris is a genus of extinct synapsid in the family Eothyrididae from the early Permian. It was a carnivorous insectivorous animal, closely related to Oedaleops. Only the skull of Eothyris, first described in 1937, is known. It had a 6-centimetre-long (2.4-inch) skull, and its total estimated length was 30 centimetres. Eothyris is one of the most primitive synapsids known and is probably very similar to the common ancestor of all synapsids in many respects. The only known specimen of Eothyris was collected from the Artinskian-lower.

Ctenorhachis is an extinct genus of the family Sphenacodontidae. Ctenorhachis lived in the Early Permian epoch. Ctenorhachis was related to Dimetrodon, but did not belong to the same subfamily as Dimetrodon and Sphenacodon, being a more basal member of Sphenacodontidae. Two specimens are known that have been found from the Wichita Group outcropping in Baylor and Archer counties, north-central Texas. Only the vertebrae and pelvis are known. Articulated vertebrae from the holotype specimen possess blade like neural spines that are greatly enlarged, although not nearly to the extent that can be seen in more derived sphenacodontids such as Dimetrodon and Secodontosaurus, in which they form a large sail. The pelvis is nearly identical to that of Dimetrodon. As suggested in the original description of the genus, Ctenorhachis may represent a short-spined sexual dimorph, although the authors find this unlikely.

Echinerpeton is an extinct genus of synapsid, including the single species Echinerpeton intermedium from the Late Carboniferous of Nova Scotia, Canada. The name means 'spiny lizard' (Greek). Along with its contemporary Archaeothyris, Echinerpeton is the oldest known synapsid, having lived around 308 million years ago. It is known from six small, fragmentary fossils, which were found in an outcrop of the Morien Group near the town of Florence. The most complete specimen preserves articulated vertebrae with high neural spines, indicating that Echinerpeton was a sail-backed synapsid like the better known Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon, and Edaphosaurus. However, the relationship of Echinerpeton to these other forms is unclear, and its phylogenetic placement among basal synapsids remains uncertain.

Macromerion is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsids, specifically Pelycosaurs, in the family Sphenacodontidae from Late Carboniferous deposits in the Czech Republic. It was named as a species of Labyrinthodon in 1875 and as its own genus in 1879.

Raranimus is an extinct genus of therapsids of the Middle Permian. It was described in 2009 from a partial skull found in 1998 from the Dashankou locality of the Qingtoushan Formation, outcropping in the Qilian Mountains of Gansu, China. The genus is the most basal known member of the clade Therapsida, to which the later Mammalia belong.

Gordodon is an extinct genus of non-mammalian synapsid that lived during the Early Permian of what is now Otero County, New Mexico. It was a member of the herbivorous sail-backed family Edaphosauridae and contains only a single species, the type species G. kraineri. Gordodon is unusual among early synapsids for its teeth, which were arranged similarly to those of modern mammals and unlike the simple, uniform lizard-like teeth of other early herbivorous synapsids. Gordodon had large incisor-like teeth at the front, followed by a prominent gap between them and a short row of peg-like teeth at the back. Gordodon was also relatively long-necked for an early synapsid, with elongated and gracile vertebrae in its neck and back. Like other edaphosaurids, Gordodon had a tall sail on its back made from the bony neural spines of its vertebrae. The spines also had bony knobs on them, a common trait of edaphosaurids, but the knobs of Gordodon are also unique for being more slender, thorn-like and randomly arranged along the spines. It is estimated to have been rather small at 1 m in length excluding the tail and 34 kg (75 lb) in weight.