Related Research Articles

The Canning Stock Route is a track that runs from Halls Creek in the Kimberley region of Western Australia to Wiluna in the mid-west region. With a total distance of around 1,850 km (1,150 mi) it is the longest historic stock route in the world.

Munga-Thirri National Park, formerly known as the Simpson Desert National Park, is the largest national park in Queensland, Australia, 1,495 km west of Brisbane. The park covers an area of 10,120 square kilometres (3,910 sq mi) in the Simpson Desert surrounding Poeppel Corner in the west of the locality of Birdsville in the Central West region of Queensland.

Lasseter's Reef refers to the purported discovery, announced by Harold Bell Lasseter in 1929 and 1930, of a fabulously rich gold deposit in a remote and desolate corner of central Australia. Lasseter's accounts of the find are conflicting and its precise location remains a mystery—if it exists.

The Hon. David Wynford Carnegie was an explorer and gold prospector in Western Australia. In 1896 he led an expedition from Coolgardie through the Gibson and Great Sandy Deserts to Halls Creek, and then back again.

Ooldea, known as Yuldea and various other names by Western Desert peoples (Aṉangu), is a tiny settlement in South Australia. It is on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain, 863 km (536 mi) west of Port Augusta on the Trans-Australian Railway. Ooldea is 143 km (89 mi) from the bitumen Eyre Highway.

Lake Mackay, known as Wilkinkarra to the Indigenous Pintupi people, is the largest of hundreds of ephemeral salt lakes scattered throughout the Pilbara and northern parts of the Goldfields-Esperance region of Western Australia and the Northern Territory. It is located on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert.

Donald Finlay Fergusson Thomson OBE was an Australian anthropologist and ornithologist. he is known for his studies of and friendship with the Pintupi and Yolngu peoples, and for his intervention in the Caledon Bay crisis.

Aputula is a remote Indigenous Australian community in the Northern Territory of Australia. It is 317 km (197 mi) south of Alice Springs and 159 km (99 mi) east of Kulgera roadhouse on the Stuart Highway, near the border with South Australia. The Finke River, which is dry for most of the year except during occasional floods and is part of the Lake Eyre basin, passes within a few kilometres of the community.

The Coniston massacre, which took place in the region around the Coniston cattle station in the then Territory of Central Australia from 14 August to 18 October 1928, was the last known officially sanctioned massacre of Indigenous Australians and one of the last events of the Australian Frontier Wars.

Australian feral camels are introduced populations of dromedary, or one-humped, camel. Imported as valuable beasts-of-burden from British India and Afghanistan during the 19th century, many were casually released into the wild after motorised transport negated the use of camels in the early 20th century. This resulted in a fast-growing feral population with numerous ecological, agricultural and social impacts.

The Bindibu expedition was a series of three field trips mounted by anthropologist Donald Thomson to meet with and learn from Pintupi Indigenous Australians between 1957 and 1965.

A message stick is a public communication device used by Aboriginal Australians. The objects were carried by messengers over long distances and were used for reinforcing a verbal message. Although styles vary, they are generally oblong lengths of wood with motifs engraved on all sides. They have traditionally been used across continental Australia, to convey messages between Aboriginal nations, clans and language groups. In the 1880s, they became objects of anthropological study, but there has been little research on them published since then. Message sticks are non-restricted since they were intended to be seen by others, often from a distance. They are nonetheless frequently mistaken for tjurungas.

Coolamon is an anglicised version of the Wiradjuric word guliman used to describe an Australian Aboriginal carrying vessel.

David Lindsay was an Australian explorer and surveyor and a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, London.

"The Dreamtime Duck of the Never Never" is a 1993 Scrooge McDuck comic by Don Rosa. It is the seventh of the original 12 chapters in the series The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck. The story takes place from 1893 to 1896.

Duncan McIntyre was an Australian explorer who followed in the tracks of Burke and Wills. In 1864 he laid claim to the property now called Dalgonally in North-West Queensland, and found evidence of Ludwig Leichhardt's final expedition. He subsequently led a party in search of Leichhardt, but died of fever during the search.

The Kelly Hills are a mountain range at the southern end of the Northern Territory of Australia. It is located in the locality of Petermann directly north of the Musgrave Ranges and about 50 kilometres (31 mi) northeast of Amaṯa in South Australia. Its highest point is about 870 metres (2,850 ft) above sea level. Mount Robert, at the eastern end of the range, is about 796 metres (2,612 ft) above sea level. The area is known as Aputjilpinya in the native Yankunytjatjara language. It forms part of an important Mala Dreaming track that runs between Uluṟu and Ulkiya.

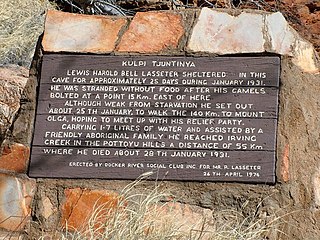

Tjunti is a soakage site near Kaḻṯukatjara, in the Northern Territory of Australia. It is located where the Hull River cuts through the Petermann Ranges, about 36 kilometres (22 mi) to the southeast of Kaḻṯukatjara, 41 km (25 mi) by road along the Tjukaruru Road. Tjunti is known as the site where the famous gold prospector Harold B. Lasseter took refuge on his fatal search for Lasseter's Reef. An outstation was established here in 1977, and belongs to a Pitjantjatjara family.

The Warnman, also spelt Wanman, are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Australia's Pilbara region.

The Carnegie expedition of 1896 was led by David Carnegie. It covered territory in the centre of Western Australia, including the Gibson and Great Sandy Deserts.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Thomson, Donald, Bindibu Country, Nelson Publishing, Melbourne, 1975.

- ↑ Thomson, Donald F., "The Bindibu Expedition: exploration among the desert Aborigines of Western Australia", The Geographical Journal, vol. 128, part 1 (March 1962), pp. 1–14, [143]–157, 262-278. [Q 306.0899915 THO]

- ↑ Don McLeod, How the West was Lost, self-published, Port Hedland, 1984, pp27-28