The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the exchange value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of "socially necessary labor" required to produce it. The contrasting system is typically known as the subjective theory of value.

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that specifically has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

In 20th-century discussions of Karl Marx's economics, the transformation problem is the problem of finding a general rule by which to transform the "values" of commodities into the "competitive prices" of the marketplace. This problem was first introduced by Marxist economist Conrad Schmidt and later dealt with by Marx in chapter 9 of the draft of volume 3 of Capital. The essential difficulty was this: given that Marx derived profit, in the form of surplus value, from direct labour inputs, and that the ratio of direct labour input to capital input varied widely between commodities, how could he reconcile this with a tendency toward an average rate of profit on all capital invested among industries, if such a tendency exists?

The organic composition of capital (OCC) is a concept created by Karl Marx in his theory of capitalism, which was simultaneously his critique of the political economy of his time. It is derived from his more basic concepts of 'value composition of capital' and 'technical composition of capital'. Marx defines the organic composition of capital as "the value-composition of capital, in so far as it is determined by its technical composition and mirrors the changes of the latter". The 'technical composition of capital' measures the relation between the elements of constant capital and variable capital. It is 'technical' because no valuation is here involved. In contrast, the 'value composition of capital' is the ratio between the value of the elements of constant capital involved in production and the value of the labor. Marx found that the special concept of 'organic composition of capital' was sometimes useful in analysis, since it assumes that the relative values of all the elements of capital are constant.

Use value or value in use is a concept in classical political economy and Marxist economics. It refers to the tangible features of a commodity which can satisfy some human requirement, want or need, or which serves a useful purpose. In Karl Marx's critique of political economy, any product has a labor-value and a use-value, and if it is traded as a commodity in markets, it additionally has an exchange value, defined as the proportion by which a commodity can be exchanged for other entities, most often expressed as a money-price.

In political economy and especially Marxian economics, exchange value refers to one of the four major attributes of a commodity, i.e., an item or service produced for, and sold on the market, the other three attributes being use value, economic value, and price. Thus, a commodity has the following:

Labour power is the capacity to do work, a key concept used by Karl Marx in his critique of capitalist political economy. Marx distinguished between the capacity to do work, i.e. labour power, and the physical act of working, i.e. labour. Labour power exists in any kind of society, but on what terms it is traded or combined with means of production to produce goods and services has historically varied greatly.

In Marxism, the valorisation or valorization of capital is the increase in the value of capital assets through the application of value-forming labour in production. The German original term is "Verwertung" but this is difficult to translate. The first translation of Capital by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling, under Engels' editorship, renders "Verwertung" in different ways depending on the context, for example as "creation of surplus-value", "self-expanding value", "increase in value" and similar expressions. These renderings were also used in the US Untermann revised edition, and the Eden and Cedar Paul translation. It has also been wrongly rendered as "realisation of capital".

Surplus product is a concept theorised by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. Roughly speaking, it is the extra goods produced above the amount needed for a community of workers to survive at its current standard of living. Marx first began to work out his idea of surplus product in his 1844 notes on James Mill's Elements of political economy.

The law of the value of commodities, known simply as the law of value, is a central concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy first expounded in his polemic The Poverty of Philosophy (1847) against Pierre-Joseph Proudhon with reference to David Ricardo's economics. Most generally, it refers to a regulative principle of the economic exchange of the products of human work, namely that the relative exchange-values of those products in trade, usually expressed by money-prices, are proportional to the average amounts of human labor-time which are currently socially necessary to produce them within the capitalist mode of production.

Prices of production is a concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy, defined as "cost-price + average profit". A production price can be thought of as a type of supply price for products; it refers to the price levels at which newly produced goods and services would have to be sold by the producers, in order to reach a normal, average profit rate on the capital invested to produce the products.

Productive and unproductive labour are concepts that were used in classical political economy mainly in the 18th and 19th centuries, which survive today to some extent in modern management discussions, economic sociology and Marxist or Marxian economic analysis. The concepts strongly influenced the construction of national accounts in the Soviet Union and other Soviet-type societies.

Abstract labour and concrete labour refer to a distinction made by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It refers to the difference between human labour in general as economically valuable worktime versus human labour as a particular activity that has a specific useful effect within the (capitalist) mode of production.

In economics, economic value is a measure of the benefit provided by a good or service to an economic agent, and value for money represents an assessment of whether financial or other resources are being used effectively in order to secure such benefit. Economic value is generally measured through units of currency, and the interpretation is therefore "what is the maximum amount of money a person is willing and able to pay for a good or service?” Value for money is often expressed in comparative terms, such as "better", or "best value for money", but may also be expressed in absolute terms, such as where a deal does, or does not, offer value for money.

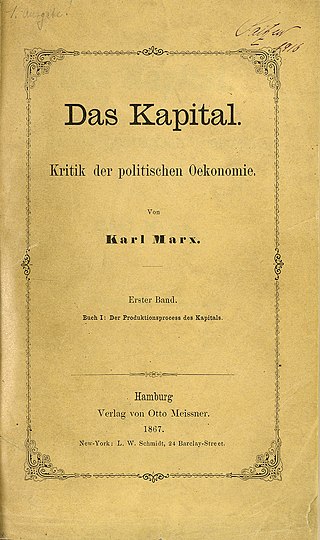

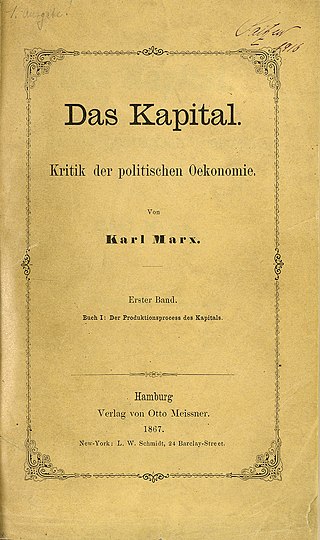

Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I: The Process of Production of Capital is the first of three treatises that make up Das Kapital, a critique of political economy by the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx. First published on 14 September 1867, Volume I was the product of a decade of research and redrafting and is the only part of Das Kapital to be completed during Marx's life. It focuses on the aspect of capitalism that Marx refers to as the capitalist mode of production or how capitalism organises society to produce goods and services.

In classical political economy and especially Karl Marx's critique of political economy, a commodity is any good or service produced by human labour and offered as a product for general sale on the market. Some other priced goods are also treated as commodities, e.g. human labor-power, works of art and natural resources, even though they may not be produced specifically for the market, or be non-reproducible goods. This problem was extensively debated by Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Karl Rodbertus-Jagetzow, among others. Value and price are not equivalent terms in economics, and theorising the specific relationship of value to market price has been a challenge for both liberal and Marxist economists.

Criticisms of the labor theory of value affect the historical concept of labor theory of value (LTV) which spans classical economics, liberal economics, Marxian economics, neo-Marxian economics, and anarchist economics. As an economic theory of value, LTV is widely attributed to Marx and Marxian economics despite Marx himself pointing out the contradictions of the theory, because Marx drew ideas from LTV and related them to the concepts of labour exploitation and surplus value; the theory itself was developed by Adam Smith and David Ricardo. LTV criticisms therefore often appear in the context of economic criticism, not only for the microeconomic theory of Marx but also for Marxism, according to which the working class is exploited under capitalism, while little to no focus is placed on those responsible for developing the theory.

Constant capital, is a concept created by Karl Marx and used in Marxian political economy. It refers to one of the forms of capital invested in production, which contrasts with variable capital. The distinction between constant and variable refers to an aspect of the economic role of factors of production in creating a new value.

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cost of the materials, plant and labour power. The concept originated in Ricardian socialism, with the term "surplus value" itself being coined by William Thompson in 1824; however, it was not consistently distinguished from the related concepts of surplus labor and surplus product. The concept was subsequently developed and popularized by Karl Marx. Marx's formulation is the standard sense and the primary basis for further developments, though how much of Marx's concept is original and distinct from the Ricardian concept is disputed. Marx's term is the German word "Mehrwert", which simply means value added, and is cognate to English "more worth".

Marxian economics, or the Marxian school of economics, is a heterodox school of political economic thought. Its foundations can be traced back to Karl Marx's critique of political economy. However, unlike critics of political economy, Marxian economists tend to accept the concept of the economy prima facie. Marxian economics comprises several different theories and includes multiple schools of thought, which are sometimes opposed to each other; in many cases Marxian analysis is used to complement, or to supplement, other economic approaches. Because one does not necessarily have to be politically Marxist to be economically Marxian, the two adjectives coexist in usage, rather than being synonymous: They share a semantic field, while also allowing both connotative and denotative differences. An example of this can be found in the works of Soviet economists like Lev Gatovsky, who sought to apply Marxist economic theory to the objectives, needs, and political conditions of the socialist construction in the Soviet Union, contributing to the development of Soviet Political Economy.