The Mon are an ethnic group who inhabit Lower Myanmar's Mon State, Kayin State, Kayah State, Tanintharyi Region, Bago Region, the Irrawaddy Delta, and several areas in Thailand. The native language is Mon, which belongs to the Monic branch of the Austroasiatic language family and shares a common origin with the Nyah Kur language, which is spoken by the people of the same name that live in Northeastern Thailand. A number of languages in Mainland Southeast Asia are influenced by the Mon language, which is also in turn influenced by those languages.

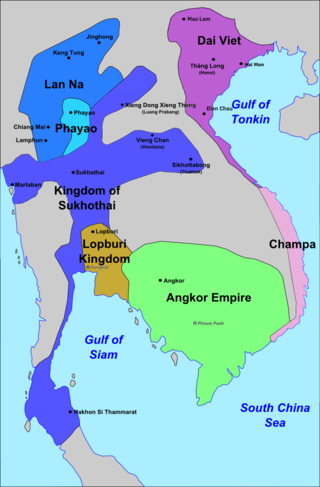

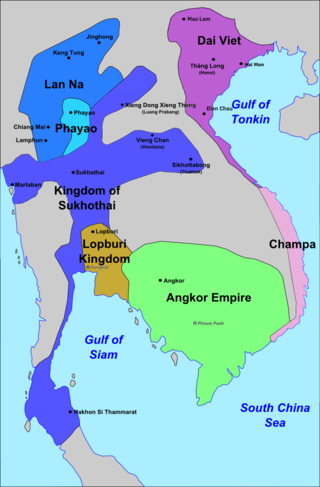

The Sukhothai Kingdom was a post-classical Siamese kingdom (maṇḍala) in Mainland Southeast Asia surrounding the ancient capital city of Sukhothai in present-day north-central Thailand. The kingdom was founded by Si Inthrathit in 1238 and existed as an independent polity until 1438, when it fell under the influence of the neighboring Ayutthaya after the death of Borommapan.

Thai New Year or Songkran, also known as Songkran Festival, Songkran Splendours, is the Thai New Year's national holiday. Songkran is on 13 April every year, but the holiday period extends from 14 to 15 April. In 2018 the Thai cabinet extended the festival nationwide to seven days, 9–16 April, to enable citizens to travel home for the holiday. In 2019, the holiday was observed 9–16 April as 13 April fell on a Saturday. In 2024, Songkran was extended to almost the entire month, starting on the first of April, and ending on the twenty-first, departing from the traditional 3-day format. And with the New Year of many calendars of Southeast and South Asia, in keeping with the Buddhist calendar and also coincides with New Year in Hindu calendar such as Vishu, Bihu, Pohela Boishakh, Pana Sankranti, Vaisakhi. The New Year takes place at around the same time as the new year celebrations of many regions of South Asia like China, India, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

Phra Bat Somdet Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok Maharat, personal name Thongduang (ทองด้วง), also known as Rama I, was the founder of the Rattanakosin Kingdom and the first King of Siam from the reigning Chakri dynasty. His full title in Thai is Phra Bat Somdet Phra Paramoruracha Maha Chakri Boromanat Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok. He ascended the throne in 1782, following the deposition of King Taksin of Thonburi. He was also celebrated as the founder of Rattanakosin as the new capital of the reunited kingdom.

Cambodian New Year, also known as Choul Chnam Thmey, Moha Sangkran or Sangkran, is the traditional celebration of the solar new year in Cambodia. A three-day public holiday in the country, the observance begins on New Year's Day, which usually falls on 13 April or 14 April, which is the end of the harvesting season, when farmers enjoy the fruits of their labor before the rainy season begins. Khmers living abroad may choose to celebrate during a weekend rather than just specifically 13 April through 16 April. The Khmer New Year coincides with the traditional solar new year in several parts of India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Laos and Thailand.

The Khmer people are an Austroasiatic ethnic group native to Cambodia. They comprise over 95% of Cambodia's population of 17 million. They speak the Khmer language, which is part of the larger Austroasiatic language family alongside Mon and Vietnamese.

Thai people are a Southeast Asian ethnic group native to Thailand. In a narrower and ethnic sense, the Thais are also a Tai ethnic group dominant in Central and Southern Thailand. Part of the larger Tai ethno-linguistic group native to Southeast Asia as well as Southern China and Northeast India, Thais speak the Sukhothai languages, which is classified as part of the Kra–Dai family of languages. The majority of Thais are followers of Theravada Buddhism.

Water festivals are vibrant celebrations that occur across the globe, often marking the start of a new year or season. These festivals are deeply rooted in cultural and religious traditions, and they showcase the importance of water as a life-giving resource. In Asia, countries like Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, and the Xishuangbanna Prefecture region of China celebrate their respective new years with lively water festivals such as Songkran, Bunpimay, Thingyan, and Chaul Chnam Thmey. These festivities involve the joyous splashing of water, symbolizing purification and renewal. Beyond Southeast Asia and China, other countries have their own unique water-themed celebrations, from the Holi festival of colors in India to the Water Battle of Spain. These festivals serve as a reminder of the universal significance of water in our lives and our connection to it.

The Thonburi Kingdom was a major Siamese kingdom which existed in Southeast Asia from 1767 to 1782, centered around the city of Thonburi, in Siam or present-day Thailand. The kingdom was founded by Taksin the Great, who reunited Siam following the collapse of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, which saw the country separate into five warring regional states. The Thonburi Kingdom oversaw the rapid reunification and reestablishment of Siam as a preeminient military power within mainland Southeast Asia, overseeing the country's expansion to its greatest territorial extent up to that point in its history, incorporating Lan Na, the Laotian kingdoms, and Cambodia under the Siamese sphere of influence.

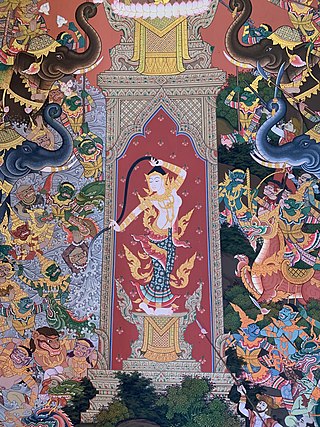

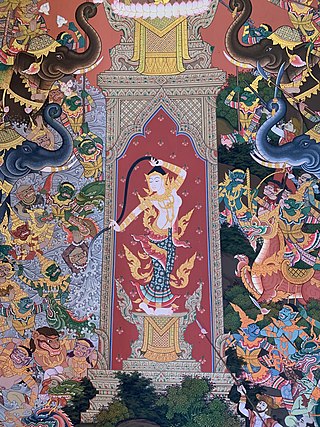

Dance in Thailand is the main dramatic art form in Thailand. Thai dance can be divided into two major categories, high art and low art.

Sinhalese New Year, generally known as Aluth Avurudda in Sri Lanka, is a Sri Lankan holiday that celebrates the traditional New Year of the Sinhalese people and Tamil population of Sri Lanka. It is a major anniversary celebrated by not only the Sinhalese and Tamil people but by most Sri Lankans. The timing of the Sinhala Tamil New Year coincides with the new year celebrations of many traditional calendars of South and Southeast Asia. The festival has close semblance to the Tamil New year and other South and Southeast Asian New Years. It is a public holiday in Sri Lanka. It is generally celebrated on 13 April or 14 April and traditionally begins at the sighting of the new moon.

Chofa is a Lao and Thai architectural decorative ornament that adorns the top at the end of wat and palace roofs in most Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. It resembles a tall thin bird and looks hornlike. The chofa is generally believed to represent the mythical creature Garuda, half bird and half man, who is the vehicle of the Hindu god Vishnu.

Chula Sakarat or Chulasakarat is a lunisolar calendar derived from the Burmese calendar, whose variants were in use by most mainland Southeast Asian kingdoms down to the late 19th century. The calendar is largely based on an older version of the Hindu calendar though unlike the Indian systems, it employs a version of the Metonic cycle. The calendar therefore has to reconcile the sidereal years of the Hindu calendar with Metonic cycle's tropical years by adding intercalary months and intercalary days on irregular intervals.

Pana Sankranti,, also known as Maha Bishuba Sankranti, is the traditional new year day festival of Odia people in Odisha, India. The festival occurs in the solar Odia calendar on the first day of the traditional solar month of Meṣa, hence equivalent lunar month Baisakha. This falls on the Purnimanta system of the Indian Hindu calendar. It therefore falls on 13/14 April every year on the Gregorian calendar.

Vasundharā or Dharaṇī is a chthonic goddess from Buddhist mythology of Theravada in Southeast Asia. Similar earth deities include Pṛthivī, Kṣiti, and Dharaṇī, Vasudhara bodhisattva in Vajrayana and Bhoomi devi and Prithvi in hinduism.

Mesha Sankranti refers to the first day of the solar cycle year, that is the solar New Year in the Hindu luni-solar calendar. The Hindu calendar also has a lunar new year, which is religiously more significant. The solar cycle year is significant in Assamese, Odia, Punjabi, Malayalam, Tamil, and Bengali calendars.

Anti-Thai sentiment involves hostility, discrimination or hatred that is directed towards people in Thailand, or the state of Thailand.

The makuṭa, variously known in several languages as makuta, mahkota, magaik, mokot, mongkut or chada, is a type of headdress used as crowns in the Southeast Asian monarchies of today's Cambodia and Thailand, and historically in Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Laos and Myanmar. They are also used in classical court dances in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand; such as khol, khon, the various forms of lakhon, as well as wayang wong dance drama. They feature a tall pointed shape, are made of gold or a substitute, and are usually decorated with gemstones. As a symbol of kingship, they are featured in the royal regalia of both Cambodia and Thailand.

The traditional New Year in many South and Southeast Asian cultures is based on the sun's entry into the constellation Aries. In modern times, it is usually reckoned around 14 April.

The Khom script is a Brahmic script and a variant of the Khmer script used in Thailand and Laos, which is used to write Pali, Sanskrit, Khmer, Thai and Lao (Isan).