Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminoles. White Americans classified them as "civilized" because they had adopted attributes of the Anglo-American culture.

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as the state of Oklahoma.

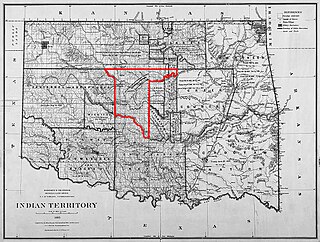

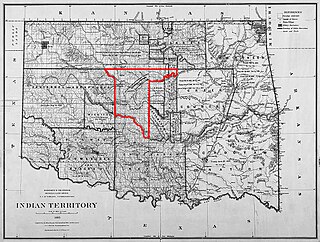

The Unassigned Lands in Oklahoma were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek (Muskogee) and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled. By 1883, it was bounded by the Cherokee Outlet on the north, several relocated Indian reservations on the east, the Chickasaw lands on the south, and the Cheyenne-Arapaho reserve on the west. The area amounted to 1,887,796.47 acres.

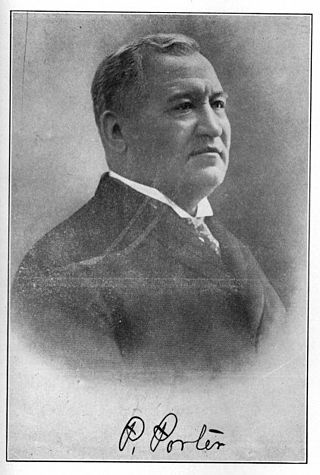

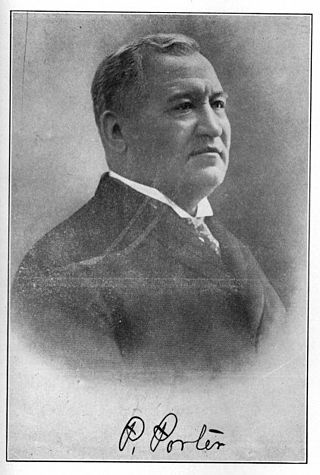

Pleasant Porter, was an American Indian statesman and the last elected Principal Chief of the Creek Nation, serving from 1899 until his death.

The Great Seal of Oklahoma was officially adopted in 1907 and is used to authenticate certain documents issued by the Government of Oklahoma. The phrase is used both for the physical seal itself, which is kept by the Secretary of State, and more generally for the design impressed upon it.

The Constitution of the State of Oklahoma is the governing document of the U.S. State of Oklahoma. Adopted in 1907, Oklahoma ratified the United States Constitution on November 16, 1907, as the 46th U.S. state. At its ratification, the Oklahoma Constitution was the lengthiest governing document of any government in the U.S. All U.S. state constitutions are subject to federal judicial review; any provision can be nullified if it conflicts with the U.S. Constitution.

The history of Oklahoma refers to the history of the state of Oklahoma and the land that the state now occupies. Areas of Oklahoma east of its panhandle were acquired in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, while the Panhandle was not acquired until the U.S. land acquisitions following the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

Alexander Lawrence Posey was an American poet, humorist, journalist, and politician in the Creek Nation. He founded the Eufaula Indian Journal in 1901, the first Native American daily newspaper. For several years he published editorial letters known as the Fus Fixico Letters, written by a fictional figure who commented pointedly about Muscogee Nation, Indian Territory, and United States politics during the period of the dissolution of tribal governments and communal lands. He served as secretary to the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention and drafted much of the constitution for its proposed Native American state, but Congress rejected the proposal. Posey died young, drowned while trying to cross the flooding North Canadian River in Oklahoma.

Confederate Units of Indian Territory consisted of Native Americans from the Five Civilized Tribes — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. The 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles were commanded by the highest ranking Native American of the war: Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, who also became the last Confederate General to surrender on June 23, 1865. There was also a series of Union units of Indian Territory.

The Cherokee Male Seminary was a tribal college established in 1846 by the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. Opening in 1851, it was one of the first institutions of higher learning in the United States to be founded west of the Mississippi River.

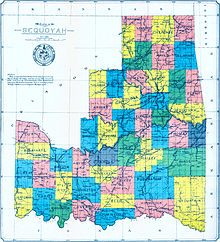

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention was an American Indian-led attempt to secure statehood for Indian Territory as an Indian-controlled jurisdiction, separate from the Oklahoma Territory. The proposed state was to be called the State of Sequoyah.

Greenwood "Green" McCurtain was a Choctaw statesman and law enforcement officer, and the last elected Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation, serving a total of four elected two-year terms. After 1906 and dissolution of tribal governments under the Dawes Act prior to Oklahoma's annexation and achieving statehood, McCurtain was appointed as chief by Theodore Roosevelt. He served in that capacity until his death in 1910, and was the last freely-elected Chief of the Choctaws until 1971.

The Atoka Agreement is a document signed by representatives of the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian Nations and members of the United States Dawes Commission on April 23, 1897, at Atoka, Indian Territory. It provided for the allotment of communal tribal lands of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations in the Indian Territory to individual households of members of the tribes, who were certified as citizens of the tribes. Land in excess of the allotments could be sold to non-natives. Provisions of this agreement were later incorporated into the Curtis Act of 1898, which provided for widespread allotment of communal tribal lands.

The Cherokee Nation was a legal, autonomous, tribal government in North America recognized from 1794 to 1907. It was often referred to simply as "The Nation" by its inhabitants. The government was effectively disbanded in 1907, after its land rights had been extinguished, prior to the admission of Oklahoma as a state. During the late 20th century, the Cherokee people reorganized, instituting a government with sovereign jurisdiction known as the Cherokee Nation. On July 9, 2020, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had never been disestablished in the years before allotment and Oklahoma Statehood.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, a significant number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas had been relocated from the Southeastern United States to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi. The inhabitants of the eastern part of the Indian Territory, the Five Civilized Tribes, were suzerain nations with established tribal governments, well established cultures, and legal systems that allowed for slavery. Before European Contact these tribes were generally matriarchial societies, with agriculture being the primary economic pursuit. The bulk of the tribes lived in towns with planned streets, residential and public areas. The people were ruled by complex hereditary chiefdoms of varying size and complexity with high levels of military organization.

Sequoyah Bay State Park is on the western shore of Fort Gibson Lake in Wagoner County, Oklahoma. It is 4.3 miles (6.9 km) south of Wagoner, Oklahoma on State Highway 16. It offers several campgrounds, each named for a notable chief of the Five Civilized Tribes. These include: Chief Attacullaculla, Cherokee; Chief Pushmataha, Choctaw; Chief Osceola, Seminole; Chief Opothleyahola, Creek; and Chief Payamataha, Chickasaw.

Pickens County was a political subdivision of the Chickasaw Nation in the Indian Territory from 1855, prior to Oklahoma being admitted as a state in 1907. The county was one of four that comprised the Chickasaw Nation. Following statehood, its territory was divided among several Oklahoma counties that have continued to the present.