Cingulata, part of the superorder Xenarthra, is an order of armored New World placental mammals. Dasypodids and chlamyphorids, the armadillos, are the only surviving families in the order. Two groups of cingulates much larger than extant armadillos existed until recently: pampatheriids, which reached weights of up to 200 kg (440 lb) and chlamyphorid glyptodonts, which attained masses of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) or more.

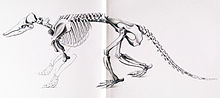

Peltephilus, the horned armadillo, is an extinct genus of armadillo xenarthran mammals that first inhabited Argentina during the Oligocene epoch, and became extinct in the Miocene epoch. Notably, the scutes on its head were so developed that they formed horns. Aside from the horned gophers of North America, it is the only known fossorial horned mammal. P. ferox had skull about 11.7 centimetres (4.6 in), and estimated body mass is around 11.07 kilograms (24.4 lb).

The Magallanes Basin or Austral Basin is a major sedimentary basin in southern Patagonia. The basin covers a surface of about 170,000 to 200,000 square kilometres and has a NNW-SSE oriented shape. The basin is bounded to the west by the Andes mountains and is separated from the Malvinas Basin to the east by the Río Chico-Dungeness High. The basin evolved from being an extensional back-arc basin in the Mesozoic to being a compressional foreland basin in the Cenozoic. Rocks within the basin are Jurassic in age and include the Cerro Toro Formation. Three ages of the SALMA classification are defined in the basin; the Early Miocene Santacrucian from the Santa Cruz Formation and Friasian from the Río Frías Formation and the Pleistocene Ensenadan from the La Ensenada Formation.

The Santacrucian age is a period of geologic time within the Early Miocene epoch of the Neogene, used more specifically with SALMA classification in South America. It follows the Colhuehuapian and precedes the Friasian age.

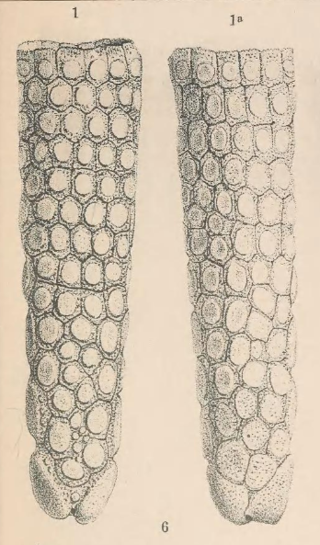

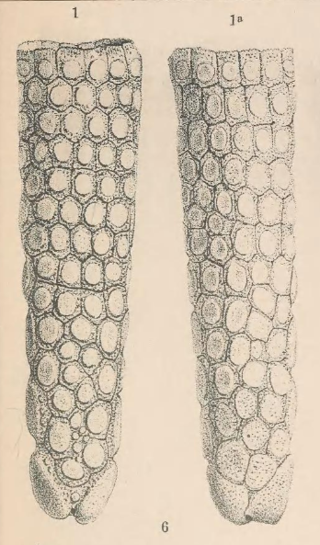

Neosclerocalyptus was an extinct genus of glyptodont that lived during the Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene of Southern South America, mostly Argentina. It was small compared to many Glyptodonts at only around 2 meters long and 360 kilograms.

Lomaphorus is a possibly dubious extinct genus of glyptodont that lived during the Pleistocene in eastern Argentina. Although many species have been referred, the genus itself is possibly dubious or synonymous with other glyptodonts like Neoslerocalyptus from the same region.

Utaetus is an extinct genus of mammal in the order Cingulata, related to the modern armadillos. The genus contains two species, Utaetus buccatus and U. magnum. It lived in the Late Paleocene to Late Eocene and its fossil remains were found in Argentina and Brazil in South America.

Epipeltephilus is an extinct genus of armadillo, belonging to the family Peltephilidae, the "horned armadillos", whose most famous relative was Peltephilus. Epipeltephilus is the last known member of its family, becoming extinct during the Chasicoan period. It was found in the Rio Mayo Formation and the Arroyo Chasicó Formation of Argentina, and in northern Chile.

Kraglievichia is an extinct genus of cingulate belonging to the family Pampatheriidae. It lived from the Late Miocene to the Early Pliocene, and its fossilized remains were discovered in South America.

Stenotatus is an extinct genus of cingulate, belonging to the family Dasypodidae. It lived from the Early to the Late Miocene in South America.

Neoglyptatelus is an extinct genus of xenarthran, belonging to the order Cingulata. It lived from the Middle to the Late Miocene, and its fossilized remains are found in South America.

Proeuphractus is an extinct genus of xenarthran, related to the modern armadillos. It lived from the Early to the Late Miocene, and its fossilized remains were discovered in South America.

Prozaedyus is an extinct genus of chlamyphorid armadillo that lived during the Middle Oligocene and Middle Miocene in what is now South America.

Eucinepeltus is an extinct genus of Glyptodont. It lived during the Early Miocene, and its fossilized remains were discovered in South America.

Glyptatelus is an extinct genus of glyptodont. It lived from the Late Eocene to the Middle Oligocene in what is now Argentina and Bolivia.

Cochlops is an extinct genus of glyptodont. It lived from the Early to Middle Miocene, and its fossilized remains have been found in South America.

Nanoastegotherium is an extinct genus of cingulate, belonging to the family Dasypodidae, which includes the modern nine-banded armadillos. The name of the genus means "small Astegotherium", referring to its small size, smaller than the modern southern long-nosed armadillo, and to its affinities with Astegotherium, with which it forms the tribe Astegotheriini, within the family Dasypodidae. Its type species is Nanoastegotherium prostatum, whose species translates to "earlier" due to its age compared to Astegotherium.

Dasypus neogaeus is an extinct species of armadillo, belonging to the genus Dasypus, alongside the modern nine-banded armadillo. The only known fossil is a single osteoderm, though it has been lost, that was found in the Late Miocene strata of Argentina.

The Santa Cruz Formation is a geological formation in the Magallanes/Austral Basin in southern Patagonia in Argentina and in adjacent areas of Chile. It dates to the late Early Miocene epoch, and is contemporaneous with eponymous Santacrucian SALMA. The formation extends from the Andes to the Atlantic coast. In its coastal section it is divided into two members, the lower, fossil rich Estancia La Costa Member, which has a lithology predominantly consisting of tuffaceous deposits and fine grained sedimentary claystone and mudstone, and the upper fossil-poor Estancia La Angelina Member, which consists of sedimentary rock, primarily claystone, mudstone, and sandstone. The environment of deposition is interpreted to have been mostly fluvial, with the lowermost part of the Estancia La Costa Member being transitional between fluvial and marine conditions. The environment of the Estancia La Costa Member is thought to have been relatively warm and humid, but likely became somewhat cooler and drier towards the end of the sequence. The Santa Cruz Formation is known for its abundance of South American native ungulates, as well as an abundance of rodents, xenarthrans, and metatherians.

Peltephilidae is a family of South American cingulates (armadillos) that lived for over 40 million years, but peaked in diversity towards the end of the Oligocene and beginning of the Miocene in what is now Argentina. They were exclusive to South America due to its geographic isolation at the time, one of many of the continent's strange endemic families. Peltephilids are one of the earliest known cingulates, diverging from the rest of Cingulata in the Early Eocene.