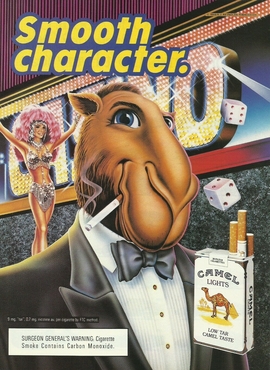

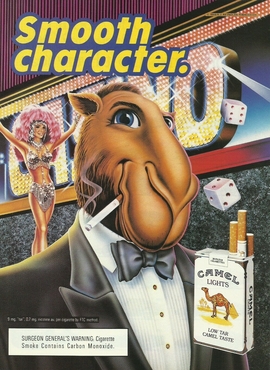

Joe Camel was an advertising mascot used by the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) for their cigarette brand Camel. The character was created in 1974 for a French advertising campaign, and was redesigned for the American market in 1988. He appeared in magazine advertisements, clothing, and billboards among other print media and merchandise.

Kool is an American brand of menthol cigarette, currently owned and manufactured by ITG Brands LLC, a subsidiary of Imperial Tobacco Company. Kool cigarettes sold outside of the United States are manufactured by British American Tobacco.

Virginia Slims is an American brand of cigarettes owned by Altria. It is manufactured by Philip Morris USA and Philip Morris International.

Pall Mall is a British brand of cigarettes produced by British American Tobacco.

Capri is an American brand of cigarettes. It is currently owned and manufactured by the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.

Newport is an American brand of menthol cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. The brand was originally named for the seaport of Newport, Rhode Island.

Nicotine marketing is the marketing of nicotine-containing products or use. Traditionally, the tobacco industry markets cigarette smoking, but it is increasingly marketing other products, such as electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products. Products are marketed through social media, stealth marketing, mass media, and sponsorship. Expenditures on nicotine marketing are in the tens of billions a year; in the US alone, spending was over US$1 million per hour in 2016; in 2003, per-capita marketing spending was $290 per adult smoker, or $45 per inhabitant. Nicotine marketing is increasingly regulated; some forms of nicotine advertising are banned in many countries. The World Health Organization recommends a complete tobacco advertising ban.

Salem is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by ITG Brands, a subsidiary of Imperial Tobacco, inside the U.S. and by Japan Tobacco outside the United States.

Doral is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.

Winston is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by ITG Brands, subsidiary of Imperial Tobacco in the United States and by Japan Tobacco outside the U.S. The brand is named after the town where R. J. Reynolds started his business which is Winston-Salem, North Carolina. As of 2017, Winston has the seventh-highest U.S. market share of all cigarette brands, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Maxwell Report.

A menthol cigarette is a cigarette infused with the compound menthol which imparts a “minty” flavor to the smoke. Menthol also decreases irritant sensations from nicotine by desensitizing receptors, making smoking feel less harsh compared to regular cigarettes. Some studies have suggested that they are more addictive. Menthol cigarettes are just as hard to quit and are just as harmful as regular cigarettes.

Vantage is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company.

Flavored tobacco products — tobacco products with added flavorings — include types of cigarettes, cigarillos and cigars, hookahs and hookah tobacco, various types of smokeless tobacco, and more recently electronic cigarettes. Flavored tobacco products are especially popular with youth and have therefore become targets of regulation in several countries.

Tobacco politics refers to the politics surrounding the use and distribution of tobacco.

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, is a federal statute in the United States that was signed into law by President Barack Obama on June 22, 2009. The Act gives the Food and Drug Administration the power to regulate the tobacco industry. A signature element of the law imposes new warnings and labels on tobacco packaging and their advertisements, with the goal of discouraging minors and young adults from smoking. The Act also bans flavored cigarettes, places limits on the advertising of tobacco products to minors and requires tobacco companies to seek FDA approval for new tobacco products.

Tobacco has a long cultural, economic, and social impact on the United States. Tobacco cultivation in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1610 lead to the expansion of British colonialism in the Southern United States. As the demand for Tobacco grew in Europe, further colonization in British America and Tobacco production saw a parallel increase. Tobacco use became normalized in American society and was heavily consumed before and after American independence.

Tobacco smoking has serious negative effects on the body. A wide variety of diseases and medical phenomena affect the sexes differently, and the same holds true for the effects of tobacco. Since the proliferation of tobacco, many cultures have viewed smoking as a masculine vice, and as such the majority of research into the specific differences between men and women with regards to the effects of tobacco have only been studied in-depth in recent years.

Philip Morris is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned by Philip Morris International. Cigarettes are manufactured by the firm worldwide except in the US, where Philip Morris USA produces tobacco products.

As nicotine is highly addictive, marketing nicotine-containing products is regulated in most jurisdictions. Regulations include bans and regulation of certain types of advertising, and requirements for counter-advertising of facts generally not included in ads. Regulation is circumvented using less-regulated media, such as Facebook, less-regulated nicotine delivery products, such as e-cigarettes, and less-regulated ad types, such as industry ads which claim to discourage nicotine addiction but seem, according to independent studies, to promote teen nicotine use.

The history of nicotine marketing stretches back centuries. Nicotine marketing has continually developed new techniques in response to historical circumstances, societal and technological change, and regulation. Counter marketing has also changed, in both message and commonness, over the decades, often in response to pro-nicotine marketing.