This article's lead section may need to be rewritten.(November 2021) |

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

|

This is a timeline of African-American history, the part of history that deals with African Americans.

Contents

- 16th century

- 17th century

- 18th century

- 1776–1783 American Revolution

- 19th century

- 1800–1859

- 1860–1874

- 1863–1877 Reconstruction Era

- 1875–1899

- 20th century

- 1900–1949

- 1925–1949

- 1940s to 1970

- 1945–1975 The Civil Rights Movement

- 1950–1959

- 1960–1969

- 1970–2000

- 21st century

- 2001–2010

- 2011–2020

- 2021-2022

- See also

- Footnotes

- Further reading

- External links

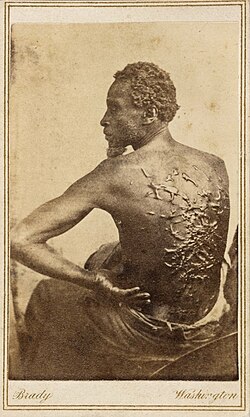

Europeans arrived in what would become the present day United States of America on August 9, 1526. With them, they brought families from Africa that they had captured and enslaved with intentions of establishing themselves and future generations of Europeans off of the bodies of these African families.

During the American Revolution of 1776–1783, enslaved African Americans in the South escaped to British lines as they were promised freedom to fight with the British; additionally, many free blacks in the North fight with the colonists for the rebellion, and the Vermont Republic (a sovereign nation at the time) becomes the first future state to abolish slavery. Following the Revolution, numerous slaveholders in the Upper South free their slaves.

The importation of slaves became a felony in 1808.

After the American Civil War began in 1861, tens of thousands of enslaved African Americans of all ages escaped to Union lines for freedom. Later on, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, formally freeing slaves in the Confederate States of America. After the American Civil War ended, the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits slavery (except as punishment for crime), was passed in 1865.

In the mid-20th century, the civil rights movement occurred, and legalized racial segregation and discrimination was thus outlawed.