Ulmus glabraHudson, the wych elm or Scots elm, has the widest range of the European elm species, from Ireland eastwards to the Ural Mountains, and from the Arctic Circle south to the mountains of the Peloponnese and Sicily, where the species reaches its southern limit in Europe; it is also found in Iran. A large deciduous tree, it is essentially a montane species, growing at elevations up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft), preferring sites with moist soils and high humidity. The tree can form pure forests in Scandinavia and occurs as far north as latitude 67°N at Beiarn in Norway. It has been successfully introduced as far north as Tromsø and Alta in northern Norway (70°N). It has also been successfully introduced to Narsarsuaq, near the southern tip of Greenland (61°N).

The field elm cultivar 'Atinia' , commonly known as the English elm, formerly common elm and horse may, and more lately the Atinian elm, was, before the spread of Dutch elm disease, the most common field elm in central southern England, though not native there, and one of the largest and fastest-growing deciduous trees in Europe. R. H. Richens noted that elm populations exist in north-west Spain and northern Portugal, and on the Mediterranean coast of France that "closely resemble the English elm" and appear to be "trees of long standing" in those regions rather than recent introductions. Augustine Henry had earlier noted that the supposed English elms planted extensively in the Royal Park at Aranjuez from the late 16th century onwards, specimens said to have been introduced from England by Philip II and "differing in no respects from the English elm in England", behaved as native trees in Spain. He suggested that the tree "may be a true native of Spain, indigenous in the alluvial plains of the great rivers, now almost completely deforested".

Ulmus minor subsp. minor, the narrow-leaved elm, was the name used by R. H. Richens (1983) for English field elms that were not English elm, Cornish elm, Lock elm or Guernsey elm. Many publications, however, continue to use plain Ulmus minor for Richens's subspecies, a name Richens reserved for the undifferentiated continental field elms. Dr Max Coleman of Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh argued in his 2002 paper 'British Elms' that there was no clear distinction between species and subspecies.

Ulmus × hollandica 'Vegeta', sometimes known as the Huntingdon Elm, is an old English hybrid cultivar raised at Brampton, near Huntingdon, by nurserymen Wood & Ingram in 1746, allegedly from seed collected at nearby Hinchingbrooke Park. In Augustine Henry's day, in the later 19th century, the elms in Hinchingbrooke Park were U. nitens. Richens, noting that wych elm is rare in Huntingdonshire, normally flowering four to six weeks later than field elm, pointed out that unusually favourable circumstances would have had to coincide to produce such seed: "It is possible that, some time in the eighteenth century, the threefold requirements of synchronous flowering of the two species, a south-west wind", "and a mild spring permitting the ripening of the samaras, were met."

Ulmus laciniata(Trautv.) Mayr, known variously as the Manchurian, cut-leaf, or lobed elm, is a deciduous tree native to the humid ravine forests of Japan, Korea, northern China, eastern Siberia and Sakhalin, growing alongside Cercidiphyllum japonicum, Aesculus turbinata, and Pterocarya rhoifolia, at elevations of 700–2200 m, though sometimes lower in more northern latitudes, notably in Hokkaido.

The field elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Stricta', known as Cornish elm, was commonly found in South West England, Brittany, and south-west Ireland, until the arrival of Dutch elm disease in the late 1960s. The origin of Cornish elm in the south-west of Britain remains a matter of contention. It is commonly assumed to have been introduced from Brittany. It is also considered possible that the tree may have survived the ice ages on lands to the south of Cornwall long since lost to the sea. Henry thought it "probably native in the south of Ireland". Dr Max Coleman of Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, arguing in his 2002 paper on British elms that there was no clear distinction between species and subspecies, suggested that known or suspected clones of Ulmus minor, once cultivated and named, should be treated as cultivars, preferred the designation U. minor 'Stricta' to Ulmus minor var. stricta. The DNA of 'Stricta' has been investigated and the cultivar is now known to be a clone.

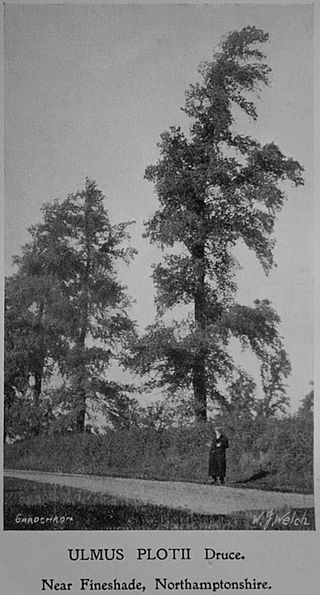

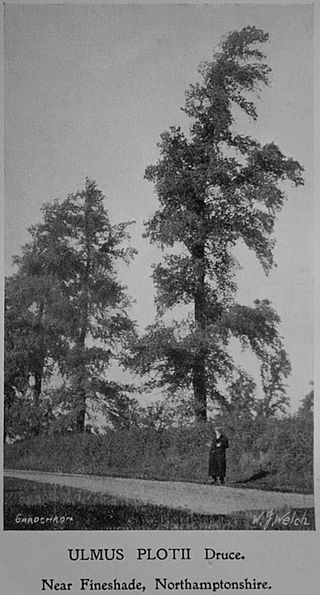

The field elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Plotii', commonly known as Lock elm or Lock's elm, Plot's elm or Plot elm, and first classified as Ulmus sativaMill. var. Lockii and later as Ulmus plotii by Druce in 1907-11, is endemic mainly to the East Midlands of England, notably around the River Witham in Lincolnshire, in the Trent Valley around Newark-on-Trent, and around the village of Laxton, Northamptonshire. Ronald Melville suggested that the tree's distribution may be related to river valley systems, in particular those of the Trent, Witham, Welland, and Nene. Two further populations existed in Gloucestershire. It has been described as Britain's rarest native elm, and recorded by The Wildlife Trust as a nationally scarce species.

The Field Elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Sarniensis', known variously as Guernsey elm, Jersey elm, Wheatley elm, or Southampton elm, was first described by MacCulloch in 1815 from trees on Guernsey, and was planted in the Royal Horticultural Society's gardens in the 1820s. It was listed in the Loddiges catalogue of 1836 as Ulmus sarniensis and by Loudon in Hortus lignosus londinensis (1838) as U. campestris var. sarniensis. The origin of the tree remains obscure; Richens believed it "a mutant of a French population of Field elm", noting that "elms of similar leaf-form occur in Cotentin and in northern Brittany. They vary much in habit but some have a tendency to pyramidal growth. Whether the distinctive habit first developed on the mainland or in Guernsey is uncertain."

Ulmus × hollandica 'Major' is a distinctive cultivar that in England came to be known specifically as theDutch Elm, although all naturally occurring Field Elm Ulmus minor × Wych Elm U. glabra hybrids are loosely termed 'Dutch elm'. It is also known by the cultivar name 'Hollandica'. Nellie Bancroft considered 'Major' either an F2 hybrid or a backcrossing with one of its parents.

Ulmus × hollandicaMill. , often known simply as Dutch elm, is a natural hybrid between Wych elm and field elm Ulmus minor which commonly occurs across Europe wherever the ranges of the parent species overlap. In England, according to the field-studies of R. H. Richens, "The largest area [of hybridization] is a band extending across Essex from the Hertfordshire border to southern Suffolk. The next largest is in northern Bedfordshire and adjoining parts of Northamptonshire. Comparable zones occur in Picardy and Cotentin in northern France". Crosses between U. × hollandica and either of the parent species are also classified as U. × hollandica. Ulmus × hollandica hybrids, natural and artificial, have been widely planted elsewhere.

The hybrid elm cultivar Ulmus × hollandica 'Belgica', one of a number of hybrids arising from the crossing of Wych Elm with a variety of Field Elm, was reputedly raised in the nurseries of the Abbey of the Dunes, Veurne, in 1694. Popular throughout Belgium and the Netherlands in the 19th century both as an ornamental and as a shelter-belt tree, it was the 'Hollandse iep' in these countries, as distinct from the tree known as 'Dutch Elm' in Great Britain and Ireland since the 17th century: Ulmus × hollandica 'Major'. In Francophone Belgium it was known as orme gras de Malines.

Ulmus 'Exoniensis', the Exeter elm, was discovered near Exeter, England, in 1826, and propagated by the Ford & Please nursery in that city. Traditionally believed to be a cultivar of the Wych Elm U. glabra, its fastigiate shape when young, upward-curving tracery, small samarae and leaves, late leaf-flush and late leaf-fall, taken with its south-west England provenance, suggest a link with the Cornish Elm, which shares these characteristics. The seed, however, is on the stalk side of the samara, a feature of wych elm and its cultivars, whereas in hybrids it would be displaced towards the notch.

The elm cultivar Ulmus 'Hertfordensis Latifolia' was listed by Loudon in Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838) as "the broad-leaved Hertfordshire Elm", and later mentioned, as Ulmus campestris hertfordensis latifolia, by Boulger in the Gardener's Chronicle, but without description. It was considered "probably U. carpinifolia" by Green, though broad leaves point to a possible Ulmus × hollandica hybrid identity. Hybrids of this type were once common in eastern Hertfordshire.

The 'dwarf' elm cultivar Ulmus 'Jacqueline Hillier' ('JH') is an elm of uncertain origin. It was cloned from a specimen found in a private garden in Selly Park, Birmingham, England, in 1966. The garden's owner told Hillier that it might have been introduced from outside the country by a relative. Hillier at first conjectured U. minor, as did Heybroek (2009). Identical-looking elm cultivars in Russia are labelled forms of Siberian Elm, Ulmus pumila, which is known to produce 'JH'-type long shoots. Melville considered 'JH' a hybrid cultivar from the 'Elegantissima' group of Ulmus × hollandica. Uncertainty about its parentage has led most nurserymen to list the tree simply as Ulmus 'Jacqueline Hillier'. 'JH' is not known to produce flowers and samarae, or root suckers.

The Field Elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Coritana' was originally claimed by Melville, while he was searching in the neighbourhood of Leicestershire in 1936 for U. elegantissima, as a new species, which he called U. coritana. He later recorded its distribution in the counties of Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, Norfolk, Oxfordshire, Suffolk and Warwickshire. Richens, however, dismissed U. coritana as 'an artificial aggregate' of local forms of Field Elm. Bean noted (1988) that Melville's U. coritana was not recognised in the Flora of the British Isles as a species distinct from U. carpinifolia [:U. minor].

The Field Elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Suberosa', commonly known as the Cork-barked elm, is a slow-growing or dwarf form of conspicuously suberose Field Elm. Of disputed status, it is considered a distinct variety by some botanists, among them Henry (1913), Krüssmann (1984), and Bean (1988), and is sometimes cloned and planted as a cultivar. Henry said the tree "appears to be a common variety in the forests of central Europe", Bean noting that it "occurs in dry habitats". By the proposed rule that known or suspected clones of U. minor, once cultivated and named, should be treated as cultivars, the tree would be designated U. minor 'Suberosa'. The Späth nursery of Berlin distributed an U. campestris suberosa alataKirchn. [:'corky-winged'] from the 1890s to the 1930s.

The Field Elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Viminalis Betulaefolia' (:'birch-leaved') is an elm tree of uncertain origin. An U. betulaefolia was listed by Loddiges of Hackney, London, in the catalogue of 1836, an U. campestris var. betulaefolia by Loudon in Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838), and an U. betulifoliaBooth by the Lawson nursery of Edinburgh. Henry described an U. campestris var. betulaefolia at Kew in 1913, obtained from Fulham nurseryman Osborne in 1879, as "scarcely different from var. viminalis ". Melville considered the tree so named at Kew a form of his U. × viminalis, while Bean (1988), describing U. 'Betulaefolia', likewise placed it under U. 'Viminalis' as an apparently allied tree. Loudon and Browne had noted that some forms of 'Viminalis' can be mistaken for a variety of birch. An U. campestris betulaefolia was distributed by Hesse's Nurseries, Weener, Germany, in the 1930s.

The field elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Viminalis' (:'willow-like'), occasionally referred to as the twiggy field elm, was raised by Masters in 1817, and listed in 1831 as U. campestris viminalis, without description. Loudon added a general description in 1838, and the Cambridge University Herbarium acquired a leaf specimen of the tree in 1866. Moss, writing in 1912, said that the Ulmus campestris viminalis from Cambridge University Herbarium was the only elm he thought agreed with the original Plot's elm as illustrated by Dr. Plot in 1677 from specimens growing in an avenue and coppice at Hanwell near Banbury. Elwes and Henry (1913) also considered Loudon's Ulmus campestris viminalis to be Dr Plot's elm. Its 19th-century name, U. campestris var. viminalis, led the cultivar to be classified for a time as a variety of English Elm. On the Continent, 'Viminalis' was the Ulmus antarcticaHort., 'zierliche Ulme' [:'dainty elm'] of Kirchner's Arboretum Muscaviense (1864).

The hybrid elm cultivar Ulmus × hollandica 'Viminalis' [:osier-leaved] was listed by the Späth nursery of Berlin as Ulmus scabraMill. var. viminalis in 1890 and as Ulmus montana viminalis from 1892. Though Späth's catalogues stated that it was "also distributed under the name planera aquatica", it remained in his lists under 'elm' and was accessioned by the Dominion Arboretum, Ottawa, and by the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh as an elm cultivar. A similar misidentification occurred in the mid-20th century, when the Siberian elm cultivar Ulmus pumila 'Poort Bulten' was for many years commercially propagated under the name Planera aquatica or 'water elm'. As the leaves of osier or Salix viminalis, however, differ markedly from those of Planera aquatica, being long, thin and tapering at both ends, Spath's name 'Viminalis' for this elm cultivar confirms that its leaves were not Planera-like. The probable explanation for the early distribution name is that Planera was the old name for Zelkova, a close relative of elm with willow-like leaves. It is therefore unlikely that 'Viminalis' was related in any way to the 19th-century elm cultivar Ulmus 'Planeroides'.