Victorian fashion comprises the various fashions and trends in British culture that emerged and developed in the United Kingdom and the British Empire throughout the Victorian era, roughly from the 1830s through the first decade of the 1900s. The period saw many changes in fashion, including changes in styles, fashion technology and the methods of distribution. Various movement in architecture, literature, and the decorative and visual arts as well as a changing perception of the traditional gender roles also influenced fashion.

1860s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by extremely full-skirted women's fashions relying on crinolines and hoops and the emergence of "alternative fashions" under the influence of the Artistic Dress movement.

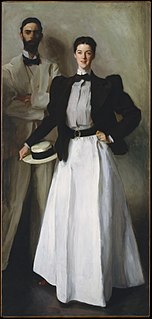

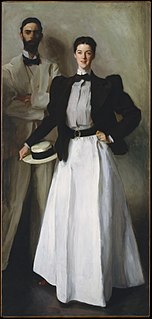

Fashion in the 1890s in European and European-influenced countries is characterized by long elegant lines, tall collars, and the rise of sportswear. It was an era of great dress reforms led by the invention of the drop-frame safety bicycle, which allowed women the opportunity to ride bicycles more comfortably, and therefore, created the need for appropriate clothing.

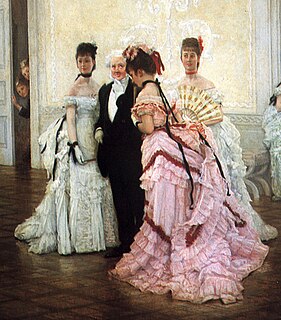

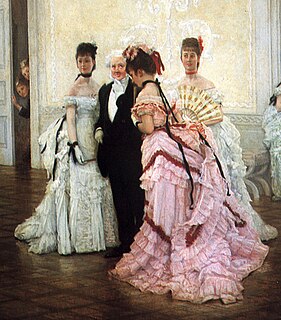

1870s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a gradual return to a narrow silhouette after the full-skirted fashions of the 1850s and 1860s.

1830s fashion in Western and Western-influenced fashion is characterized by an emphasis on breadth, initially at the shoulder and later in the hips, in contrast to the narrower silhouettes that had predominated between 1800-1820.

1840s fashion in European and European-influenced clothing is characterized by a narrow, natural shoulder line following the exaggerated puffed sleeves of the later 1820s and 1830s. The narrower shoulder was accompanied by a lower waistline for both men and women.

1850s fashion in Western and Western-influenced clothing is characterized by an increase in the width of women's skirts supported by crinolines or hoops, and the beginnings of dress reform. Masculine styles began to originate more in London, while female fashions originated almost exclusively in Paris.

Fashion in the period 1550–1600 in Western European clothing was characterized by increased opulence. Contrasting fabrics, slashes, embroidery, applied trims, and other forms of surface ornamentation remained prominent. The wide silhouette, conical for women with breadth at the hips and broadly square for men with width at the shoulders had reached its peak in the 1530s, and by mid-century a tall, narrow line with a V-shaped waist was back in fashion. Sleeves and women's skirts then began to widen again, with emphasis at the shoulder that would continue into the next century. The characteristic garment of the period was the ruff, which began as a modest ruffle attached to the neckband of a shirt or smock and grew into a separate garment of fine linen, trimmed with lace, cutwork or embroidery, and shaped into crisp, precise folds with starch and heated irons.

Fashion in the years 1750–1775 in European countries and the colonial Americas was characterised by greater abundance, elaboration and intricacy in clothing designs, loved by the Rococo artistic trends of the period. The French and English styles of fashion were very different from one another. French style was defined by elaborate court dress, colourful and rich in decoration, worn by such iconic fashion figures as Marie Antoinette.

Fashion in the period 1600–1650 in Western European clothing is characterized by the disappearance of the ruff in favour of broad lace or linen collars. Waistlines rose through the period for both men and women. Other notable fashions included full, slashed sleeves and tall or broad hats with brims. For men, hose disappeared in favour of breeches.

During the 1820s in European and European-influenced countries, fashionable women's clothing styles transitioned away from the classically influenced "Empire"/"Regency" styles of c. 1795–1820 and re-adopted elements that had been characteristic of most of the 18th century, such as full skirts and clearly visible corseting of the natural waist.

Fashion in the period 1660–1700 in Western European clothing is characterized by rapid change. The style of this era is known as Baroque. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War and the Restoration of England's Charles II, military influences in men's clothing were replaced by a brief period of decorative exuberance which then sobered into the coat, waistcoat and breeches costume that would reign for the next century and a half. In the normal cycle of fashion, the broad, high-waisted silhouette of the previous period was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. This period also marked the rise of the periwig as an essential item of men's fashion.

Fashion in the 1880s in Western and Western-influenced countries is characterized by the return of the bustle. The long, lean line of the late 1870s was replaced by a full, curvy silhouette with gradually widening shoulders. Fashionable waists were low and tiny below a full, low bust supported by a corset. The Rational Dress Society was founded in 1881 in reaction to the extremes of fashionable corsetry.

Fashion in the period 1795–1820 in European and European-influenced countries saw the final triumph of undress or informal styles over the brocades, lace, periwigs and powder of the earlier 18th century. In the aftermath of the French Revolution, no one wanted to appear to be a member of the French aristocracy, and people began using clothing more as a form of individual expression of the true self than as a pure indication of social status. As a result, the shifts that occurred in fashion at the turn of the 19th century granted the opportunity to present new public identities that also provided insights into their private selves. Katherine Aaslestad indicates how "fashion, embodying new social values, emerged as a key site of confrontation between tradition and change."

Fashion in the period 1500–1550 in Western Europe is marked by voluminous clothing worn in an abundance of layers. Contrasting fabrics, slashes, embroidery, applied trims, and other forms of surface ornamentation became prominent. The tall, narrow lines of the late Medieval period were replaced with a wide silhouette, conical for women with breadth at the hips and broadly square for men with width at the shoulders. Sleeves were a center of attention, and were puffed, slashed, cuffed, and turned back to reveal contrasting linings.

Fashion in 15th-century Europe was characterized by a series of extremes and extravagances, from the voluminous robes called houppelandes with their sweeping floor-length sleeves to the revealing doublets and hose of Renaissance Italy. Hats, hoods, and other headdresses assumed increasing importance, and were draped, jewelled, and feathered.

Fashion in the period 1900–1909 in the Western world continued the long elegant lines of the 1890s. Tall, stiff collars characterize the period, as do women's broad hats and full "Gibson Girl" hairstyles. A new, columnar silhouette introduced by the couturiers of Paris late in the decade signaled the approaching abandonment of the corset as an indispensable garment.

Fashion in the twenty years between 1775–1795 in Western culture became simpler and less elaborate. These changes were a result of emerging modern ideals of selfhood, the declining fashionability of highly elaborate Rococo styles, and the widespread embrace of the rationalistic or "classical" ideals of Enlightenment philosophes.

A mantua from the collection at Kimberley Hall in Norfolk is the earliest complete European women's costume in the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Also known as the Kimberley Gown, this formal dress is a mantua, a two-piece costume consisting of a draped open robe and a matching underskirt or petticoat, and has been dated to ca. 1690–1700.