A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characteristics: floatplanes and flying boats; the latter are generally far larger and can carry far more. Seaplanes that can also take off and land on airfields are in a subclass called amphibious aircraft, or amphibians. Seaplanes were sometimes called hydroplanes, but currently this term applies instead to motor-powered watercraft that use the technique of hydrodynamic lift to skim the surface of water when running at speed.

The Orteig Prize was a reward of $25,000 offered in 1919 by New York City hotel owner Raymond Orteig to the first Allied aviator, or aviators, to fly non-stop from New York City to Paris or vice versa. Several famous aviators made unsuccessful attempts at the New York–Paris flight before the relatively unknown American Charles Lindbergh won the prize in 1927 in his aircraft Spirit of St. Louis.

This is a list of aviation-related events from 1927:

This is a list of aviation-related events from 1928:

Chalk's International Airlines, formerly Chalk's Ocean Airways, was an airline with its headquarters on the grounds of Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport in unincorporated Broward County, Florida near Fort Lauderdale. It operated scheduled seaplane services to the Bahamas. Its main base was Miami Seaplane Base (MPB) until 2001, with a hub at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport. On September 30, 2007, the United States Department of Transportation revoked the flying charter for the airline, and later that year, the airline ceased operations.

Douglas Corrigan was an American aviator, nicknamed "Wrong Way" in 1938. After a transcontinental flight in July from Long Beach, California, to New York City, he then flew from Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn to Ireland, although his flight plan was filed to return to Long Beach.

Bernt Balchen was a Norwegian pioneer polar aviator, navigator, aircraft mechanical engineer and military leader. A Norwegian native, he later became an American citizen and was a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Bertrand Blanchard Acosta was a record-setting aviator and test pilot. He and Clarence D. Chamberlin set an endurance record of 51 hours, 11 minutes, and 25 seconds in the air. He later flew in the Spanish Civil War in the Yankee Squadron. He was known as the "bad boy of the air". He received numerous fines and suspensions for flying stunts such as flying under bridges or flying too close to buildings.

The America was a Fokker C-2 trimotor monoplane that was flown in 1927 by Richard E. Byrd, Bernt Balchen, George Otto Noville, and Bert Acosta on their transatlantic flight.

The Cradle of Aviation Museum is an aerospace museum located in Uniondale, New York on Long Island, established to commemorate Long Island's part in the history of aviation. It is located on land once part of Mitchel Air Force Base which, together with nearby Roosevelt Field and other airfields on the Hempstead Plains, was the site of many historic flights. So many seminal flights had occurred in the area that, by the mid-1920s, the cluster of airfields was already dubbed the "Cradle of Aviation", the origin of the museum's name.

Clarence Duncan Chamberlin was an American pioneer of aviation, being the second man to pilot a fixed-wing aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to the European mainland, while carrying the first transatlantic passenger.

Lewis Rodman Wanamaker was an American businessman and heir to the Wanamaker's department store fortune. In addition to operating stores in Philadelphia, New York City, and Paris, he was a patron of the arts, education, golf, athletics, a Native American scholarship, and of early aviation.

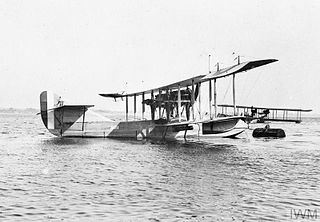

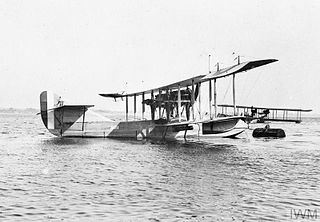

The Curtiss Model H was a family of classes of early long-range flying boats, the first two of which were developed directly on commission in the United States in response to the £10,000 prize challenge issued in 1913 by the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, for the first non-stop aerial crossing of the Atlantic. As the first aircraft having transatlantic range and cargo-carrying capacity, it became the grandfather development leading to early international commercial air travel, and by extension, to the modern world of commercial aviation. The last widely produced class, the Model H-12, was retrospectively designated Model 6 by Curtiss' company in the 1930s, and various classes have variants with suffixed letters indicating differences.

George Otto Noville, also known as "Noville" and "Rex," was a pioneer in polar and trans-Atlantic aviation in the 1920s, and winner of the Distinguished Flying Cross. He served with Commander Richard E. Byrd on the historic 1926 flight to the North Pole, as third in command. He was flight engineer on the America, and was executive officer of Byrd's Second Antarctic Exploration 1933-35. Mount Noville and Noville Peninsula in Antarctica are named after him.

The Wanamaker Triplane or Curtiss Model T, retroactively renamed Curtiss Model 3 was a large experimental four-engined triplane patrol flying boat of World War I. It was the first four-engined aircraft built in the United States. Only a single example (No.3073) was completed. At the time, the Triplane was the largest seaplane in the world.

The Wright-Bellanca WB-2, was a high wing monoplane aircraft designed by Giuseppe Mario Bellanca, initially for Wright Aeronautical then later Columbia Aircraft Corp.

Robertson Aircraft Corporation was a post-World War I American aviation service company based at the Lambert-St. Louis Flying Field near St. Louis, Missouri, that flew passengers and U.S. Air Mail, gave flying lessons, and performed exhibition flights. It also modified, re-manufactured, and resold surplus military aircraft including Standard J, Curtiss Jenny/Canuck, DeHavilland DH-4, Curtiss Oriole, Spad, Waco, and Travel Air types in addition to Curtiss OX-5 engines.

David Hugh McCulloch was an early American aviator who worked with Glenn Curtiss from 1912. Curtiss was a contemporary and competitor to the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville, who had made the first flights at Kitty Hawk in 1903. Curtiss won the world's first air race at Reims in France in August 1909, and was now becoming the driving force in American aviation. McCulloch's early work with Curtiss consisted of demonstrating, training and selling Curtiss planes and participating in early developments of flight. He trained the First Yale Unit, and in two consecutive days in 1917, he and several of his pupils from the First Yale Unit made flights that convinced the Navy to bring aircraft aboard ships. Later, McCulloch was co-pilot with Holden C. Richardson and flight commander John Henry Towers of the NC-3, the leader of the three Navy flying boats making the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

Arthur Burns "Pappy" Chalk was an American aviation pioneer and the founder of Chalk's Ocean Airways, once the world's oldest continuously operating airline. Born on a farm in Unionville, Illinois, Chalk was an enrolled Choctaw Freedman. At 11, Chalk left home and moved to Paducah, Kentucky, where he worked as a bicycle mechanic. In 1911, he received flying lessons from the famed pilot Tony Jannus in exchange for repairing Jannus's aircraft. Chalk then purchased his own plane, barnstormed for several years, and relocated to Miami in 1917.