Afrofuturism is a cultural aesthetic, philosophy of science, and history that explores the intersection of the African diaspora culture with science and technology. It addresses themes and concerns of the African diaspora through technoculture and speculative fiction, encompassing a range of media and artists with a shared interest in envisioning black futures that stem from Afro-diasporic experiences. While Afrofuturism is most commonly associated with science fiction, it can also encompass other speculative genres such as fantasy, alternate history and magic realism, and can also be found in music.

Seneca Village was a 19th-century settlement of mostly African American landowners in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, within what would become present-day Central Park. The settlement was located near the current Upper West Side neighborhood, approximately bounded by Central Park West and the axes of 82nd Street, 89th Street, and Seventh Avenue, had they been constructed through the park.

Wangechi Mutu is a Kenyan American visual artist, known primarily for her painting, sculpture, film, and performance work. Born in Kenya, Mutu now splits her time between her studio there in Nairobi and her studio in Brooklyn, New York, where she has lived and worked for over 20 years. Mutu's work has directed the female body as subject through collage painting, immersive installation, and live and video performance while exploring questions of self-image, gender constructs, cultural trauma, and environmental destruction and notions of beauty and power.

The Museum of Islamic Art is a museum on one end of the seven-kilometer-long (4.3 mi) Corniche in Doha, Qatar. As per the architect I. M. Pei's specifications, the museum is built on an island off an artificial projecting peninsula near the traditional dhow harbor. A purpose-built park surrounds the edifice on the eastern and southern facades while two bridges connect the southern front facade of the property with the main peninsula that holds the park. The western and northern facades are marked by the harbor showcasing the Qatari seafaring past. In September 2017, Qatar Museums appointed Julia Gonnella as director of MIA. In 2024 Julia Gonnella became director of the Lusail Museum and was replaced by Shaika Nasser Al-Nassr. In November 2022 the MIA became the first carbon-neutral certified museum in the Middle East Region. The museum participated in the Expo 2023 Doha from October 2023 until March 2024, with workshops and events focusing on biodiversity and sustainability.

A private collection is a privately owned collection of works or valuable items. In a museum or art gallery context, the term signifies that a certain work is not owned by that institution, but is on loan from an individual or organization, either for temporary exhibition or for the long term. This source is usually an art collector, although it could also be a school, church, bank, or some other company or organization. By contrast, collectors of books, even if they collect for aesthetic reasons, are called bibliophiles, and their collections are typically referred to as libraries.

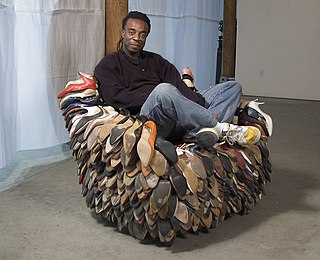

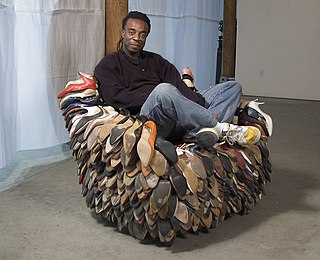

Willie Cole is a contemporary American sculptor, printer, and conceptual and visual artist. His work uses contexts of postmodern eclecticism, and combines references and appropriation from African and African-American imagery. He also has used Dada’s readymades and Surrealism’s transformed objects, as well as icons of American pop culture or African and Asian masks.

Hannah Beachler is an American production designer. The first African-American to win the Academy Award for Best Production Design, she is known for her Afrofuturist design direction of Marvel Studios film series Black Panther and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. Beachler has been involved in numerous projects directed by Beyoncé, including Lemonade and Black Is King.

Nettrice R. Gaskins is an African-American digital artist, academic, cultural critic and advocate of STEAM fields. In her work, she explores "techno-vernacular creativity" and Afrofuturism.

The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales is a 1985 collection of twenty-four folktales retold by Virginia Hamilton and illustrated by Leo and Diane Dillon. They encompass animal tales, fairy tales, supernatural tales, and tales of the enslaved Africans.

Jenn Nkiru is a Nigerian-British artist and director. She is known for directing the music video for Beyoncé's "Brown Skin Girl" and for being the second unit director of Ricky Saiz’s video for Beyoncé and Jay-Z, "APESHIT" which was released in 2018. She was selected to participate in the 2019 Whitney Biennial.

African design encompasses many forms of expression and refers to the forms of design from the continent of Africa and the African diaspora including urban design, architectural design, interior design, product design, art, and fashion design. Africa's many diverse countries are sources of vibrant design with African design influences visible in historical and contemporary art and culture around the world. The study of African design is still limited, particularly from the viewpoint of Africans, and the opportunity to expand its current definition by exploring African visual representations and introducing contemporary design applications remains immense.

Fabiola Jean-Louis is a Haitian artist working in photography, paper textile design, and sculpture. Her work examines the intersectionality of the Black experience, particularly that of women, to address the absence and imbalance of historical representation of African American and Afro-Caribbean people. Jean-Louis has earned residencies at the Museum of Art and Design (MAD), New York City, the Lux Art Institute, San Diego, and the Andrew Freedman Home in The Bronx. In 2021, Jean-Louis became the first Haitian woman artist to exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Fabiola lives and works in New York City.

Inimfon "Ini" Joshua Archibong is an industrial designer, creative director, artist, and musician who is active in product design, furniture design, environmental design, architecture, watch design, and fashion.

Zizipho Poswa is a South African artist and ceramicist based in Cape Town.

Thomas W. Commeraw, also known erroneously as Thomas H. Commereau, was an early 19th century African-American potter and businessman.

A period room is a display that represents the interior design and decorative art of a particular historical social setting usually in a museum. Though it may incorporate elements of an individual real room that once existed somewhere, it is usually by its nature a composite and fictional piece. Period rooms at encyclopedic museums may represent different countries and cultures, while those at historic house museums may represent different eras of the same structure. As with the glamorization of luxury in costume drama, this can be considered as a conservative genre that traditionally privileges Eurocentric elite views.

Michelle D. Commander is a historian and author, and serves as Deputy Director of Research and Strategic Initiatives at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

In America: An Anthology of Fashion is the 2022 high fashion art exhibition of the Anna Wintour Costume Center, a wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) which houses the collection of the Costume Institute. It is the piece of a two-part exhibit that explores fashion in the United States. This exhibit highlights stylistic narratives and histories of the American Wing Period. Each immersive period rooms reflect America from the 1700s to the 1970s and captures men's and women's fashion. The rooms also display America's domestic life and the influences of cultures, politics, and style at each period.

Cyrus Kabiru is a Kenyan visual artist, who is self taught. He is known for his sculptural eyewear made of found objects, and is part of the Afrofuturism cultural movement.