Mambas are fast-moving, highly venomous snakes of the genus Dendroaspis in the family Elapidae. Four extant species are recognised currently; three of those four species are essentially arboreal and green in colour, whereas the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, is largely terrestrial and generally brown or grey in colour. All are native to various regions in sub-Saharan Africa and all are feared throughout their ranges, especially the black mamba. In Africa there are many legends and stories about mambas.

Bungarus is a genus of venomous snakes in the family Elapidae. The genus is native to Asia. Often found on the floor of tropical forests in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Southern China, they are medium-sized, highly venomous snakes with a total length typically not exceeding 2 metres. These are nocturnal ophiophagious predators which prey primarily on other snakes at night, occasionally taking lizards, amphibians and rodents. Most species are with banded patterns acting as a warning sign to their predators. Despite being considered as generally docile and timid, kraits are capable of delivering highly potent neurotoxic venom which is medically significant with potential lethality to humans. The genus currently holds 18 species and 5 subspecies.

A snakebite is an injury caused by the bite of a snake, especially a venomous snake. A common sign of a bite from a venomous snake is the presence of two puncture wounds from the animal's fangs. Sometimes venom injection from the bite may occur. This may result in redness, swelling, and severe pain at the area, which may take up to an hour to appear. Vomiting, blurred vision, tingling of the limbs, and sweating may result. Most bites are on the hands, arms, or legs. Fear following a bite is common with symptoms of a racing heart and feeling faint. The venom may cause bleeding, kidney failure, a severe allergic reaction, tissue death around the bite, or breathing problems. Bites may result in the loss of a limb or other chronic problems or even death.

The inland taipan, also commonly known as the western taipan, small-scaled snake, or fierce snake, is a species of extremely venomous snake in the family Elapidae. The species is endemic to semiarid regions of central east Australia. Aboriginal Australians living in those regions named the snake dandarabilla. It was formally described by Frederick McCoy in 1879 and then by William John Macleay in 1882, but for the next 90 years, it was a mystery to the scientific community; no further specimens were found, and virtually nothing was added to the knowledge of this species until its rediscovery in 1972.

The black mamba is a species of highly venomous snake belonging to the family Elapidae. It is native to parts of sub-Saharan Africa. First formally described by Albert Günther in 1864, it is the second-longest venomous snake after the king cobra; mature specimens generally exceed 2 m and commonly grow to 3 m (9.8 ft). Specimens of 4.3 to 4.5 m have been reported. Its skin colour varies from grey to dark brown. Juvenile black mambas tend to be paler than adults and darken with age. Despite the common name, the skin of a black mamba is not black; the color name describes rather the inside of its mouth, which it displays when feeling threatened.

The eastern green mamba is a highly venomous snake species of the mamba genus Dendroaspis native to the coastal regions of southern East Africa. Described by Scottish surgeon and zoologist Andrew Smith in 1849, it has a slender build with a bright green back and green-yellow ventral scales. Adult females average around 2 metres in length, and males are slightly smaller.

The western green mamba is a long, thin, and highly venomous snake species of the mamba genus, Dendroaspis. This species was first described in 1844 by American herpetologist Edward Hallowell. The western green mamba is a fairly large and predominantly arboreal species, capable of navigating through trees swiftly and gracefully. It will also descend to ground level to pursue prey such as rodents and other small mammals.

(not to be confused with the Asian genus Ahaetulla, which are also referred as 'vine snakes')

Naja is a genus of venomous elapid snakes commonly known as cobras. Members of the genus Naja are the most widespread and the most widely recognized as "true" cobras. Various species occur in regions throughout Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several other elapid species are also called "cobras", such as the king cobra and the rinkhals, but neither is a true cobra, in that they do not belong to the genus Naja, but instead each belong to monotypic genera Hemachatus and Ophiophagus.

Rhamnophis is a genus of arboreal venomous snakes, commonly known as dagger-tooth tree snakes or large-eyed tree snakes, in the family Colubridae. The genus is endemic to equatorial sub-Saharan Africa. There are two recognized species.

The horned adder is a viper species. It is found in the arid region of southwest Africa, in Angola, Botswana, Namibia; South Africa, and Zimbabwe. It is easily distinguished by the presence of a single, large horn-like scale over each eye. No subspecies are currently recognized. Like all other vipers, it is venomous.

Micrurus fulvius, commonly known as the eastern coral snake, common coral snake, American cobra, and more, is a species of highly venomous coral snake in the family Elapidae. The family also contains the cobras and sea snakes. The species is endemic to the southeastern United States. It should not be confused with the scarlet snake or scarlet kingsnake, which are harmless mimics. No subspecies are currently recognized.

Telescopus, the Old World catsnakes, is a genus of 12 species of mildly venomous opisthoglyphous snakes in the family Colubridae.

Tachymenis is a genus of venomous snakes belonging to the family Colubridae. Species in the genus Tachymenis are commonly known as slender snakes or short-tailed snakes and are primarily found in southern South America. Tachymenis are rear-fanged (opisthoglyphous) and are capable of producing a medically significant bite, with at least one species, T. peruviana, responsible for human fatalities.

Jameson's mamba is a species of highly venomous snake in the family Elapidae. The species is native to equatorial Africa. A member of the mamba genus, Dendroaspis, it is slender with dull green upper parts and cream underparts and generally ranges from 1.5 to 2.2 m in total length. Described by Scottish naturalist Thomas Traill in 1843, it has two recognised subspecies. The nominate subspecies is found in central and western sub-Saharan Africa, and the eastern black-tailed subspecies is found eastern sub-Saharan Africa, mainly western Kenya.

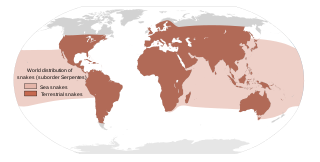

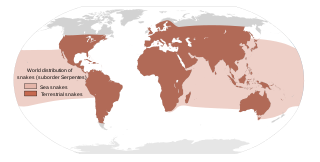

Most snakebites are caused by non-venomous snakes. Of the roughly 3,700 known species of snake found worldwide, only 15% are considered dangerous to humans. Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. There are two major families of venomous snakes, Elapidae and Viperidae. 325 species in 61 genera are recognized in the family Elapidae and 224 species in 22 genera are recognized in the family Viperidae, In addition, the most diverse and widely distributed snake family, the colubrids, has approximately 700 venomous species, but only five genera—boomslangs, twig snakes, keelback snakes, green snakes, and slender snakes—have caused human fatalities.

Philodryas olfersii is a species of venomous snake in the family Colubridae. The species is endemic to South America.

The large-eyed green tree snake, also known commonly as the splendid dagger-tooth tree snake, is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Colubrinae of the family Colubridae. The species is endemic to Africa. There are three recognized subspecies.

The spotted dagger-tooth tree snake is a species of venomous snake in the family Colubridae. The species is indigenous to Middle Africa.