The Black Peaks Formation is a geological formation in Texas whose strata date back to the Late Cretaceous. Dinosaur remains and the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi have been among the fossils reported from the formation. The boundary with the underlying Javelina Formation has been estimated at 66.5 million years old. The formation preserves the rays Rhombodus and Dasyatis, as well as many gar scales.

Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in Arizona refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arizona. The fossil record of Arizona dates to the Precambrian. During the Precambrian, Arizona was home to a shallow sea which was home to jellyfish and stromatolite-forming bacteria. This sea was still in place during the Cambrian period of the Paleozoic era and was home to brachiopods and trilobites, but it withdrew during the Ordovician and Silurian. The sea returned during the Devonian and was home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. Sea levels began to rise and fall during the Carboniferous, leaving most of the state a richly vegetated coastal plain during the low spells. During the Permian, Arizona was richly vegetated but was submerged by seawater late in the period.

The Gardener's Clay Formation is a Pleistocene geologic unit straddling the New York-New Jersey border. Fossil fish vertebrae and teeth are preserved in its sediments.

The Hannold Hill Formation is an Early Eocene (Wasatchian) geologic unit in the western United States. It preserves the fossilized remains of the ray Myliobatis and gar.

The Brushy Canyon Formation is a Permian geologic unit in Guadalupe Mountains National Park. The formation contains fan sandstones that were deposited under ancient seawater during the Middle Permian. These rocks contain abundant fish fossils like sharks' teeth preserved within small phosphatic nodules.

The Titus Canyon Formation is an Eocene geologic formation in California. H. Donald Curry collected the type specimens of the three teleosts Fundulus curryi, Fundulus euepis, and Cyprinodon breviradius in the Titus Canyon Formation. Both of these genera are present in the Titus Canyon Formation sediments of Death Valley National Park.

The Kishenehn Formation is a Paleogene stratigraphic unit in Montana. Fossil amiiforme and teleost fish have been found in outcrops of the formation's Coal Creek Member in Glacier National Park. Mosquitos have also been found in the Coal Creek Member, and have been found to be hematophagous. It is considered a Middle Eocene Lagerstätte.

The Boone Formation a discrete and definable unit of cherty limestone rock strata located in northwest Arkansas and northeast Oklahoma.

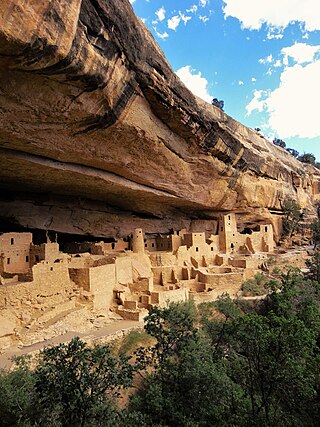

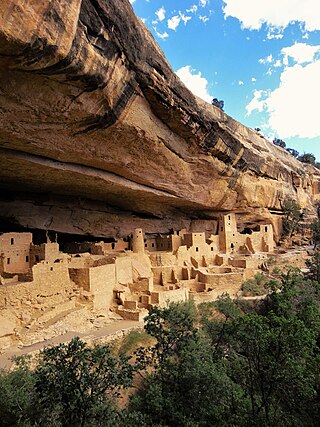

The Cliff House Sandstone is a late Campanian stratigraphic unit comprising sandstones in the western United States.

The Glenns Ferry Formation is a Pliocene stratigraphic unit in the western United States. Outcrops of the formation in Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument preserve the remains of seven fish species, five of which are extinct. These include the teleosteans Mylopharodon hagermanensis, Sigmopharyngodon idahoensis, and Ptychocheilus oregonensis, Ameirurus vespertinus, and the sunfish Archoplites taylori. A nearly complete skull of the catfish Ameirurus vespertinus was recovered in 2001 from the wall of the Smithsonian Horse Quarry.

The Lost Burro Formation is a Middle to Upper/Late Devonian geologic formation in the Mojave Desert of California in the Western United States.

The Hidden Valley Dolomite is a Silurian−Devonian geologic formation in the northern Mojave Desert of California, in the western United States.

The Mountain Springs Formation is Devonian stratigraphic unit in Arizona. The remains of both antiarch and arthrodire placoderms are known from the formation.

Blieckaspis priscillae is a pteraspidid heterostracan agnathan from the Middle Devonian of North America.

Squatirhina is a genus of Late Cretaceous cartilaginous fish whose fossils have been found in the Aguja and Pen Formations of Big Bend National Park, Texas, USA.

The St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site is a fossil site and museum at Johnson Farm in Saint George, Utah. The museum preserves thousands of dinosaur footprints right at the original site of discovery.

Gwyneddichnium is an ichnogenus from the Late Triassic of North America and Europe. It represents a form of reptile footprints and trackways, likely produced by small tanystropheids such as Tanytrachelos. Gwyneddichnium includes a single species, Gwyneddichnium major. Two other proposed species, G. elongatum and G. minore, are indistinguishable from G. major apart from their smaller size and minor taphonomic discrepancies. As a result, they are considered junior synonyms of G. major.