Mine rescue or mines rescue is the specialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of mining accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions.

Mine rescue or mines rescue is the specialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of mining accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions.

Mining laws in developed countries require trained, equipped mine rescue personnel to be available at all mining operations at surface and underground mining operations. Mine rescue teams must know the procedures used to rescue miners trapped by various hazards, including fire, explosions, cave-ins, toxic gas, smoke inhalation, and water entering the mine. Most mine rescue teams are composed of miners who know the mine and are familiar with the mining machinery they may encounter during the rescue, the layout of workings and geological conditions and working practices.[ citation needed ] Local and state governments may have teams on-call ready to respond to mine accidents.

The first mines rescuers were the colliery managers and volunteer colleagues of the victims of the explosions, roof-falls and other accidents underground. They looked for signs of life, rescued the injured, sealed off underground fires so it would be possible to reopen the pit, and recovered bodies while working in dangerous conditions sometimes at great cost to themselves. Apart from safety lamps to detect gases, they had no special equipment. [1] Most deaths in coal mines were caused by the poisonous gases caused by explosions, particularly afterdamp or carbon monoxide. Survivors of explosions were rare and most apparatus taken underground was used to fight fires or recover bodies. Early breathing apparatus derived from under-sea diving was developed and a crude nose and mouthpiece and breathing tubes was tried in France before 1800. Gas masks of various types were tried in the early-19th century: some had chemical filters, others goat skin reservoirs or metal canisters, but none eliminated carbon dioxide rendering them of limited use. [2] Theodore Schwann, a German professor working in Belgium, designed breathing apparatus based on the regenerative process in 1854 and it was exhibited in Paris in the 1870s but may never have been used. [3] [4]

Henry Fleuss developed Schwann's apparatus into a form of self-contained breathing apparatus in the 1880s and it was used after an explosion at Seaham Colliery in 1881. [3] The apparatus was further developed by Siebe Gorman into the Proto rebreather. In 1908 the Proto apparatus was chosen in a trial of equipment from several manufacturers to select the most efficient apparatus for use underground at Howe Bridge Mines Rescue Station and became the standard in rescue stations set up after the Coal Mines Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5. c. 50). [5] An early use of the breathing apparatus was in the aftermath of an explosion at the Maypole Colliery in Abram in August 1908. Six trained rescuers at Howe Bridge trained men at individual collieries in the use of the equipment and at the time of the Pretoria Pit Disaster in 1910 several hundred trained men participated in the operation. [1]

Mine rescue teams are trained in first aid, the use of a variety of tools, and the operation of self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) to work in passages filled with mine gases such as firedamp, afterdamp, chokedamp, and sometimes shallow submersion.

From 1989 to 2004, the SEFA backpack SCBA was made. Rescuers used it and its successors the Draeger rebreather and Biomarine. Narrow spaces in mines are often too constricted for bulky open circuit sets with big compressed-air cylinders.

In 2010, an all-female mine rescue team was formed at the Colorado School of Mines. [6]

Altofts Colliery manager, W.E. Garforth suggested using a "gallery" to test rescue apparatus and train rescuers in 1899 and one was built at his pit in Altofts West Yorkshire. It cost £13,000. [3] He also suggested the idea of a network of rescue stations. [7] The first British mines rescue station opened at Tankersley in 1902. It was commissioned by the West Yorkshire Coal Mine Owners Association. [8] Its building is grade II listed. [9]

In the United Kingdom a series of disasters in the 19th century brought about Royal Commissions which developed the idea of improving mine safety. The commissions influenced the Coal Mines Act 1911 which made the provision of rescue stations compulsory. [10] By 1919 there were 43 stations in the UK but as the coal industry declined from the last quarter of the 20th century many were closed, leaving six as of 2013 [update] , at Crossgates in Fife, Houghton-le-Spring in Tyne and Wear, Kellingley at Beal in North Yorkshire, Rawdon in Derbyshire, Dinas at Tonypandy in Glamorgan and at Mansfield Woodhouse in Nottinghamshire. [11] [12] The MRS Training centre at Houghton-le-Spring opened in 1913 is one of the six surviving British rescue stations which are operated by MRS Training and Rescue. [13] It is a Grade II listed building. [14]

Mines rescue featured in the 1952 film The Brave Don't Cry which was a testimony to the Knockshinnoch disaster. Mine rescuers have often been recognised in Britain by the award of gallantry medals.

In Britain, mines rescue teams may be called to investigate holes in the ground that have appeared because of land surface subsidence into old mineshafts and mine workings.[ citation needed ]

In Poland, there are groups of rescuers in each mine. In addition, there are three specialized emergency stations in the Bytom, Jaworzno and Wodzisław Śląski. They are operational 24/7.

In South Africa, mine rescue teams are also known as "Proto teams", a reference to the original Siebe Gorman Proto oxygen rebreather equipment they used. [15]

During World War I the British army mined underneath enemy lines in occupied France, and mine rescue training was required for the soldiers, often skilled coal-miners who undertook the work as part of the Tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers. Much documentation on military mining activities was classified information until 1961. [16]

Firedamp is any flammable gas found in coal mines, typically coalbed methane. It is particularly found in areas where the coal is bituminous. The gas accumulates in pockets in the coal and adjacent strata and when they are penetrated the release can trigger explosions. Historically, if such a pocket was highly pressurized, it was termed a "bag of foulness".

A mining accident is an accident that occurs during the process of mining minerals or metals. Thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially from underground coal mining, although accidents also occur in hard rock mining. Coal mining is considered much more hazardous than hard rock mining due to flat-lying rock strata, generally incompetent rock, the presence of methane gas, and coal dust. Most of the deaths these days occur in developing countries, and rural parts of developed countries where safety measures are not practiced as fully. A mining disaster is an incident where there are five or more fatalities.

Afterdamp is the toxic mixture of gases left in a mine following an explosion caused by methane-rich firedamp, which itself can initiate a much larger explosion of coal dust. The term is etymologically and practically related to other terms for underground mine gases—such as firedamp, white damp, and black damp, with afterdamp being composed, rather, primarily by carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and nitrogen, with highly toxic stinkdamp-constituent hydrogen sulfide possibly also present. However, the high content of carbon monoxide is the component that kills, preferentially combining with haemoglobin in the blood and thus depriving victims of oxygen. Globally, afterdamp has caused many of the casualties in disasters of pit coalfields, including British, such as the Senghenydd colliery disaster. Such disasters continue to afflict working mines, for instance in mainland China.

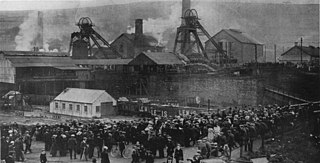

The Senghenydd colliery disaster, also known as the Senghenydd explosion, occurred at the Universal Colliery in Senghenydd, near Caerphilly, Glamorgan, Wales, on 14 October 1913. The explosion, which killed 439 miners and a rescuer, is the worst mining accident in the United Kingdom. Universal Colliery, on the South Wales Coalfield, extracted steam coal, which was much in demand. Some of the region's coal seams contained high quantities of firedamp, a highly explosive gas consisting of methane and hydrogen.

The Oaks explosion, which happened at a coal mine in West Riding of Yorkshire on 12 December 1866, remains the worst mining disaster in England. A series of explosions caused by firedamp ripped through the underground workings at the Oaks Colliery at Hoyle Mill near Stairfoot in Barnsley killing 361 miners and rescuers. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom until the 1913 Senghenydd explosion in Wales.

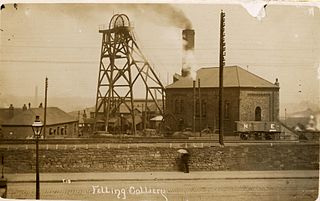

The Felling Colliery in Britain, suffered four disasters in the 19th century, in 1812, 1813, 1821 and 1847. By far the worst of the four was the 1812 disaster which claimed 92 lives on 25 May 1812. The loss of life in the 1812 disaster was one of the motivators for the development of miners' safety lamps such as the Geordie lamp and the Davy lamp.

Blackdamp is an asphyxiant, reducing the available oxygen content of air to a level incapable of sustaining human or animal life. It is not a single gas but a mixture of unbreathable gases left after oxygen is removed from the air and typically consists of nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water vapour. The term is etymologically and practically related to terms for other underground mine gases such as fire damp, white damp, stink damp, and afterdamp.

The Proto is a type of rebreather that was made by Siebe Gorman. It was an industrial breathing set and not suitable for diving. It was made from 1914 or earlier to the 1960s or later.. Also known as proto suits.

The Gresford disaster occurred on 22 September 1934 at Gresford Colliery, near Wrexham, when an explosion and underground fire killed 266 men. Gresford is one of Britain's worst coal mining disasters: a controversial inquiry into the disaster did not conclusively identify a cause, though evidence suggested that failures in safety procedures and poor mine management were contributory factors. Further public controversy was caused by the decision to seal the colliery's damaged sections permanently, meaning that only eleven of those who died were recovered.

Burngrange is an area of the Scottish village West Calder. Situated at the far west of the village it mainly consists of housing constructed for the areas mining industry in the early 20th century. On 10 January 1947, Burngrange was witness to its worst underground mining disaster, in which 15 miners perished.

Clifton Hall Colliery was one of two coal mines in Clifton on the Manchester Coalfield, historically in Lancashire which was incorporated into the City of Salford in Greater Manchester, England in 1974. Clifton Hall was notorious for an explosion in 1885 which killed around 178 men and boys.

The Brunner Mine disaster happened at 9:30 am on Thursday 26 March 1896, when an explosion deep in the Brunner Mine, in the West Coast region of New Zealand, killed all 65 miners below ground. The Brunner Mine disaster is the deadliest mining disaster in New Zealand's history.

The Knockshinnoch disaster was a mining accident that occurred in September 1950 in the village of New Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland. A glaciated lake filled with liquid peat and moss flooded pit workings, trapping more than a hundred miners underground. For several days rescue teams worked non-stop to reach the trapped men. Most were eventually rescued three days later, but 13 died. The disaster was an international media event.

The Bedford Colliery disaster occurred on Friday 13 August 1886 when an explosion of firedamp caused the death of 38 miners at Bedford No.2 Pit, at Bedford, Leigh in what then was Lancashire. The colliery, sunk in 1884 and known to be a "fiery pit", was owned by John Speakman.

Howe Bridge Mines Rescue Station was the first mines rescue station on the Lancashire Coalfield opened in 1908 in Howe Bridge, Atherton, then in the historic county of Lancashire, England.

Haig Colliery was a coal mine in Whitehaven, Cumbria, in north-west England. The mine was in operation for almost 70 years and produced high volatile strongly caking general purpose coal which was used in the local iron making industry, gas making and domestic fires. In later years, following closure of Workington Steelworks in 1980, it was used in electricity generation at Fiddler's Ferry. Situated on the coast, the underground workings of the mine spread westwards out under the Irish Sea and mining was undertaken at over 4 miles (6.4 km) out underneath the sea bed.

The Coal Mines Act 1911 amended and consolidated legislation in the United Kingdom related to collieries. A series of mine disasters in the 19th and early-20th centuries had led to commissions of enquiry and legislation to improve mining safety. The 1911 Act, sponsored by Winston Churchill, was passed by the Liberal government of H. H. Asquith. It built on earlier regulations and provided for many improvement to safety and other aspects of the coal mining industry. An important aspect was that mine owners were required to ensure there were mines rescue stations near each colliery with equipped and trained staff. Although amended several times, it was the main legislation governing coal mining for many years.

The Sneyd Colliery Disaster was a coal mining accident on 1 January 1942 in Burslem in the English city of Stoke-on-Trent. An underground explosion occurred at 7:50 am, caused by sparks from wagons underground igniting coal dust. A total of 57 men and boys died.

Bentley Colliery was a coal mine in Bentley, near Doncaster in South Yorkshire, England, that operated between 1906 and 1993. In common with many other mines, it suffered disasters and accidents. The worst Bentley disaster was in 1931 when 45 miners were killed after a gas explosion. The site of the mine has been converted into a woodland.

The 1923 Bellbird Mining Disaster took place on 1 September 1923 when there was a fire at Hetton-Bellbird coal mine, known locally as the Bellbird Colliery or mine. The coal mine was located near the village of Bellbird, which is itself three miles southwest of Cessnock in the Northern coalfields of New South Wales, Australia. The accident occurred in the No. 1 Workings of the mine and resulted in the deaths of 21 miners and their horses. At the time of the disaster the mine employed 538 people including 369 who worked underground.