Japan was occupied and administered by the Allies of World War II from the surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945, at the war's end until the Treaty of San Francisco took effect on April 28, 1952. The occupation, led by the American military with support from the British Commonwealth and under the supervision of the Far Eastern Commission, involved a total of nearly one million Allied soldiers. The occupation was overseen by the US General Douglas MacArthur, who was appointed Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers by the US President Harry S. Truman; MacArthur was succeeded as supreme commander by General Matthew Ridgway in 1951. Unlike in the occupations of Germany and Austria, the Soviet Union had little to no influence in Japan, declining to participate because it did not want to place Soviet troops under MacArthur's direct command.

The February 26 incident was an attempted coup d'état in the Empire of Japan on 26 February 1936. It was organized by a group of young Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) officers with the goal of purging the government and military leadership of their factional rivals and ideological opponents.

The Ministry of Information (MOI), headed by the Minister of Information, was a United Kingdom government department created briefly at the end of the First World War and again during the Second World War. Located in Senate House at the University of London during the 1940s, it was the central government department responsible for publicity and propaganda. The MOI was dissolved in March 1946, with its residual functions passing to the Central Office of Information (COI); which was itself dissolved in December 2011 due to the reforming of the organisation of government communications.

Shortly prior to and during World War II, and coinciding with the Second Sino-Japanese War, tens of thousands of Jewish refugees were resettled in the Japanese Empire. The onset of the European war by Nazi Germany involved the lethal mass persecutions and genocide of Jews, later known as the Holocaust, resulting in thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing east. Most ended up in Japanese-occupied China.

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941, to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the United States, including its territories and the Philippines. The efforts of the Office of Censorship to balance the protection of sensitive war related information with the constitutional freedoms of the press is considered largely successful.

The Yokusan Sonendan was an elite paramilitary youth branch of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association political party of wartime Empire of Japan established in January 1942, and based on the model of the German Sturmabteilung (stormtroopers).

The Home Ministry was a Cabinet-level ministry established under the Meiji Constitution that managed the internal affairs of Empire of Japan from 1873 to 1947. Its duties included local administration, elections, police, monitoring people, social policy and public works. In 1938, the HM's social policy was detached from itself, then the Ministry of Health and Welfare was established. In 1947, the HM was abolished under the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers restoration, then its administrative affairs were proceeded to the National Police Agency, the Ministry of Construction, the Ministry of Home Affairs and so on. In 2001, the MOHA was integrated with the Management and Coordination Agency and the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications, then the Ministry of Public Management, Home affairs, Posts and Telecommunications was established. In 2004, the MPHPT changed its English name into the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. In other words, the MIC is the direct descendant of the HM.

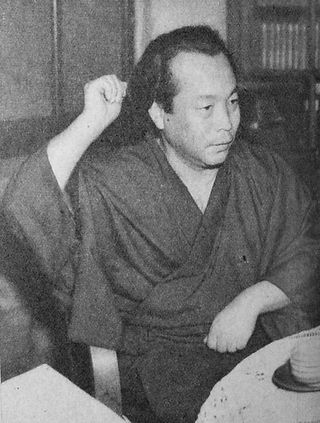

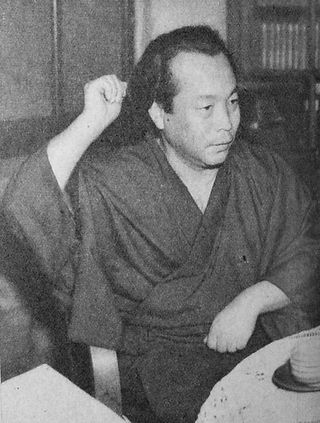

Ashihei Hino was a Japanese writer, whose works included depictions of military life during World War II. He was born in Wakamatsu and in 1937 he received the prestigious Akutagawa Prize for one of his novels, Fun'nyōtan. At that moment he was a soldier for the Japanese army in China. He then got promoted to the information corps and published numerous works about the daily lives of Japanese soldiers. It is for his war novels that he became famous during the war. His book Mugi to Heitai sold over a million copies.

Tōhōkai was a Japanese fascist political party. The party was active in Japan during the 1930s and early 1940s. Its origins lay in the right-wing political organization Kokumin Domei which was formed by Adachi Kenzō in 1933. In 1936, Nakano Seigō disagreed with Adachi on of matters of policy and formed a separate group, which he called the 'Tōhōkai'.

Censorship in Japan has taken many forms throughout the history of the country. While Article 21 of the Constitution of Japan guarantees freedom of expression and prohibits formal censorship, effective censorship of obscene content does exist and is justified by the Article 175 of the Criminal Code of Japan. Historically, the law has been interpreted in different ways—recently it has been interpreted to mean that all pornography must be at least partly censored, and a few arrests have been made based on this law.

John Reddie Black was a Scottish publisher, journalist, writer, photographer, and singer. Much of his career was spent in China and Japan where he published several newspapers including The Far East, a fortnightly newsmagazine illustrated with original photographs.

Nanjing Massacre denial is the pseudohistorical claim denying that Imperial Japanese forces murdered hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians in the city of Nanjing during the Second Sino-Japanese War. This is relevant today in Sino-Japanese relations. Most historians accept the findings of the Tokyo tribunal with respect to the scope and nature of the atrocities which were committed by the Imperial Japanese Army after the Battle of Nanjing. In Japan, however, there has been a debate over the extent and nature of the massacre with some historians attempting to downplay or outright deny that the massacre took place.

During World War II, it was estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 members of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces surrendered to Allied servicemembers prior to the end of World War II in Asia in August 1945. Also, Soviet troops seized and imprisoned more than half a million Japanese troops and civilians in China and other places. The number of Japanese soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who surrendered was limited by the Japanese military indoctrinating its personnel to fight to the death, Allied combat personnel often being unwilling to take prisoners, and many Japanese soldiers believing that those who surrendered would be killed by their captors.

Kisaburō Andō was a career officer and lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army, who served as a politician and cabinet minister in the government of the Empire of Japan during World War II.

The administrative structure of the government of the Empire of Japan on the eve of the Second World War broadly consisted of the Cabinet, the civil service, local and prefectural governments, the governments-general of Chosen (Korea) and Formosa (Taiwan) and the colonial offices. It underwent several changes during the wartime years, and was entirely reorganized when the Empire of Japan was officially dissolved in 1947.

World War I was the first war in which mass media and propaganda played a significant role in keeping the people at home informed on what occurred at the battlefields. It was also the first war in which governments systematically produced propaganda as a way to target the public and alter their opinion.

Political prisoners in Imperial Japan were detained and prosecuted by the government of the Empire of Japan for dissent, attempting to change the national character of Japan, Communist activity, or association with a group whose stated aims included the aforementioned goals. Following the dissolution of the Empire of Japan after World War II, all remaining political prisoners were released by policies issued under the Allied occupation of Japan.

Censorship in Indonesia has varied since the country declared its independence in 1945. For most of its history the government of Indonesia has not fully allowed free speech and has censored Western movies, books,films, and music as well. However, partly due to the weakness of the state and cultural factors, it has never been a country with full censorship where no critical voices were able to be printed or voiced.

Propaganda in World War II had the goals of influencing morale, indoctrinating soldiers and military personnel, and influencing civilians of enemy countries.

The Cabinet Intelligence Bureau was a government organization in Japan. It was founded in 1940 at the request of Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro. The organization's main objective was to improve pro-Japan public opinion around what was happening in World War II. Its main responsibilities included gathering information, reporting advertisements, and regulation or prohibition of publications. They distributed government propaganda both within and outside of Japan. In all, around 160 officers were employed by the organization.