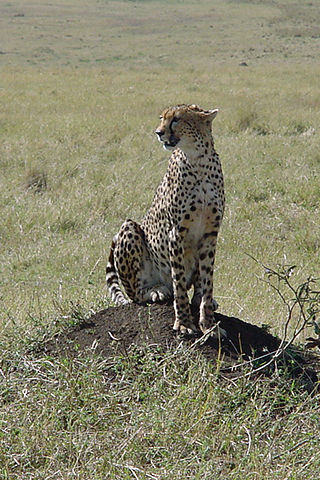

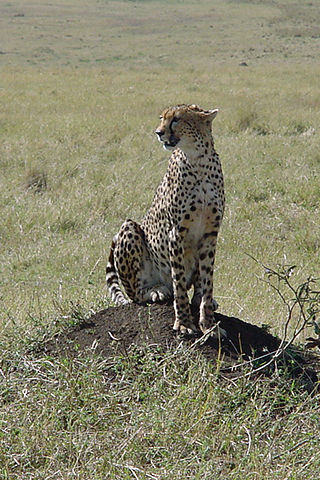

The cheetah is a large cat and the fastest land animal. It has a tawny to creamy white or pale buff fur that is marked with evenly spaced, solid black spots. The head is small and rounded, with a short snout and black tear-like facial streaks. It reaches 67–94 cm (26–37 in) at the shoulder, and the head-and-body length is between 1.1 and 1.5 m. Adults weigh between 21 and 72 kg. The cheetah is capable of running at 93 to 104 km/h ; it has evolved specialized adaptations for speed, including a light build, long thin legs and a long tail.

Acinonyx is a genus within the Felidae family. The only living species of the genus, the cheetah, lives in open grasslands of Africa and Asia.

Species reintroduction is the deliberate release of a species into the wild, from captivity or other areas where the organism is capable of survival. The goal of species reintroduction is to establish a healthy, genetically diverse, self-sustaining population to an area where it has been extirpated, or to augment an existing population. Species that may be eligible for reintroduction are typically threatened or endangered in the wild. However, reintroduction of a species can also be for pest control; for example, wolves being reintroduced to a wild area to curb an overpopulation of deer. Because reintroduction may involve returning native species to localities where they had been extirpated, some prefer the term "reestablishment".

The Asiatic lion is a lion population of the subspecies Panthera leo leo. Since the turn of the 20th century, its range has been restricted to Gir National Park and the surrounding areas in the Indian state of Gujarat. The first scientific description of the Asiatic lion was published in 1826 by the Austrian zoologist Johann N. Meyer, who named it Felis leo persicus. Until the 19th century, it occurred in Saudi Arabia, eastern Turkey, Iran, Mesopotamia, and from east of the Indus River in Pakistan to the Bengal region and the Narmada River in Central India.

The Asiatic cheetah is a critically endangered cheetah subspecies currently only surviving in Iran. Its range once spread from the Arabian Peninsula and the Near East to the Caspian region, Transcaucasus, Kyzylkum Desert and northern South Asia, but was extirpated in these regions during the 20th century. The Asiatic cheetah diverged from the cheetah population in Africa between 32,000 and 67,000 years ago.

The Northwest African cheetah, also known as the Saharan cheetah, is a cheetah subspecies native to the Sahara and the Sahel. It is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List. In 2008, the population was suspected to number less than 250 mature individuals.

The Cheetah Conservation Fund is a research and lobby institution in Namibia concerned with the study and sustenance of the country's cheetah population, the largest and healthiest in the world. Its Research and Education Centre is located 44 kilometres (27 mi) east of Otjiwarongo. The CCF was founded in 1990 by conservation biologist Laurie Marker who won the 2010 Tyler Prize for her efforts in Namibia.

Kuno National Park is a national park and Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh, India. It derives its name from Kuno River. It was established in 1981 as a wildlife sanctuary with an initial area of 344.686 km2 (133.084 sq mi) in the Sheopur and Morena districts. In 2018, it was given the status of a national park. It is part of the Khathiar-Gir dry deciduous forests ecoregion.

The Asiatic Lion Reintroduction Project is an initiative of the Indian Government to provide safeguards to the Asiatic lion from extinction in the wild by means of reintroduction. The last wild population of the Asiatic lion is found in the region of Gir Forest National Park, in the state of Gujarat. The single population faces the threats of epidemics, natural disasters and other anthropogenic factors. The project aims to establish a second independent population of Asiatic lions at the Kuno National Park in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. However, the proposed translocation has been bitterly contested by the state government.

The Yotvata Hai-Bar Nature Reserve is a 3,000-acre (12 km2) breeding and reacclimation center administered by the Israel Nature Reserves & National Parks Authority, situated in the Southern Arava near Yotvata.

The wildlife of Iran include the fauna and flora of Iran.

Banni Grasslands Reserve or Banni grasslands form a belt of arid grassland ecosystem on the outer southern edge of the desert of the marshy salt flats of Rann of Kutch in Kutch District, Gujarat State, India. They are known for rich wildlife and biodiversity and are spread across an area of 3,847 square kilometres. They are currently legally protected under the status as a protected or reserve forest in India. Though declared a protected forest more than half a century ago Gujarat state's forest department has recently proposed a special plan to restore and manage this ecosystem in the most efficient way. Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has identified this grassland reserve as one of the last remaining habitats of the cheetah in India and a possible reintroduction site for the species.

Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary also popularly known as Narayan Sarovar Wildlife Sanctuary or Narayan Sarovar Chinkara Sanctuary notified as such in April 1981 and subsequently denotified in 1995 with reduced area, is a unique eco-system near Narayan Sarovar in the Lakhpat taluka of Kutch district in the state of Gujarat, India. The desert forest in this sanctuary is said to be the only one of its kind in India. Located in the arid zone, a part of it is a seasonal wetland. It has 15 threatened wildlife species and has desert vegetation comprising thorn and scrub forests. Its biodiversity has some rare animals and birds, and rare flowering plants. Wildlife Institute of India (WII) has identified it as one of the last remaining habitats of the cheetah in India and a possible reintroduction site for the species. The most sighted animal here is the chinkara, which is currently the flagship species of the sanctuary.

The Indian aurochs is an extinct subspecies of aurochs that inhabited West Asia and the Indian subcontinent from the Late Pleistocene until its eventual extinction during the South Asian Stone Age. With no remains younger than 3,800 YBP ever recovered, the Indian aurochs was the first of the three aurochs subspecies to become extinct; the Eurasian aurochs and the North African aurochs persevered longer, with the latter being known to the Roman Empire, and the former surviving until the mid-17th century in Central Europe.

Khar Turan National Park and Touran Wildlife Refuge are adjoining protected areas in Iran. They are situated in the Semnan province, southeast of Shahrud. With a size of 1,400,000 hectares (14,000 km2), They form the second-largest reserve in Iran. Khar Turan National Park also called the little Africa in Iran, is registered as the second biosphere reserve in the world by UNESCO, Turan National Park and Wildlife Refuge is one of the astonishing expanses to observe the mysteries of the wildlife accustomed to arid and semi-arid regions of Iran. Being the second-largest reserve in this country, this park embraces arid highlands, lowlands, mounts, sands, and endless salt pans.

The East African cheetah, is a cheetah population in East Africa. It lives in grasslands and savannas of Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Somalia. The cheetah inhabits mainly the Serengeti ecosystem, including Maasai Mara, and the Tsavo landscape.

The Northeast African cheetah is a cheetah subspecies occurring in Northeast Africa. Contemporary records are known in South Sudan and Ethiopia, but population status in Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia and Sudan is unknown.

The Southeast African cheetah is the nominate cheetah subspecies native to East and Southern Africa. The Southern African cheetah lives mainly in the lowland areas and deserts of the Kalahari, the savannahs of Okavango Delta, and the grasslands of the Transvaal region in South Africa. In Namibia, cheetahs are mostly found in farmlands. In India, four cheetahs of the subspecies are living in Kuno National Park in Madhya Pradesh after having been introduced there.

The Laohu Valley Reserve (LVR) is a nature reserve located near Philippolis in the Free State and near Vanderkloof Dam in the Northern Cape of South Africa. It is a roughly 350-square-kilometre private reserve.

Laurie Marker is an American zoologist, researcher, author, educator, and one of the world's foremost cheetah experts, who founded the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) in 1990. As executive director of CCF, among many endeavors, Marker helps rehabilitate cheetahs and reintroduce them to the wild, performs research into conservation, biology and ecology, educates groups around the world, and works toward a holistic approach to saving the cheetah and its ecosystems in the wild. Before her work with CCF, Marker's career started to take off at the Wildlife Safari in the U.S., where her interest with captive cheetahs began.