Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a very high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silica and other constituents of dross, which makes it very brittle and not useful directly as a material except for limited applications.

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. Blast refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric pressure.

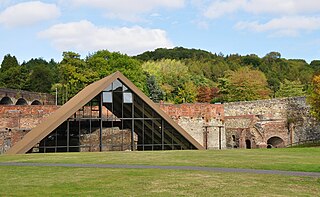

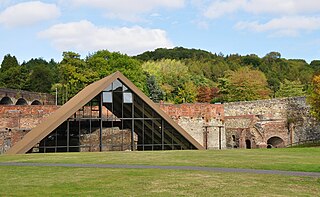

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

The Wealden iron industry was located in the Weald of south-eastern England. It was formerly an important industry, producing a large proportion of the bar iron made in England in the 16th century and most British cannon until about 1770. Ironmaking in the Weald used ironstone from various clay beds, and was fuelled by charcoal made from trees in the heavily wooded landscape. The industry in the Weald declined when ironmaking began to be fuelled by coke made from coal, which does not occur accessibly in the area.

Anthracite iron or Anthracite 'Pig Iron' is the substance created by the smelting together of anthracite coal and iron ore, that is using Anthracite coal instead of charcoal to smelt iron ores — and was an important historic advance in the late-1830s enabling great acceleration the industrial revolution in Europe and North America.

An ironworks or iron works is an industrial plant where iron is smelted and where heavy iron and steel products are made. The term is both singular and plural, i.e. the singular of ironworks is ironworks.

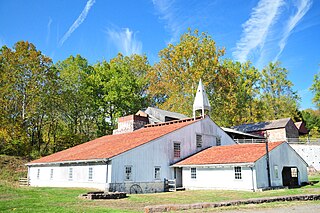

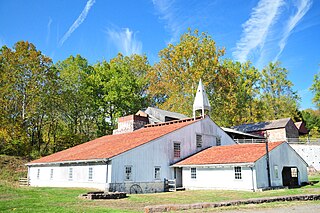

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site in southeastern Berks County, near Elverson, Pennsylvania, is an example of an American 19th century rural "iron plantation," whose operations were based around a charcoal-fired cold-blast iron blast furnace. The significant restored structures include the furnace group (blast furnace, water wheel, blast machinery, cast house and charcoal house), as well as the ironmaster's house, a company store, the blacksmith's shop, a barn and several worker's houses.

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. As this considerably reduced the fuel consumed, hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. Hot blast also allowed higher furnace temperatures, which increased the capacity of furnaces.

The Lehigh Crane Iron Company was a major ironmaking firm in the Lehigh Valley from its founding in 1839 until its sale in 1899. It was founded under the patronage of Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, and financed by their Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, which hoped to promote the then-novel technique of smelting iron ore with anthracite coal. This was an important cost and energy savings technique, since either an expensive charcoaling nor coke producing process and transport costs was totally eliminated so produced a great acceleration in the underpinnings of the American industrial revolution.

The Tannehill Ironworks is the central feature of Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park near the unincorporated town of McCalla in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Tannehill Furnace, it was a major supplier of iron for Confederate ordnance. Remains of the old furnaces are located 12 miles (19 km) south of Bessemer off Interstate 59/Interstate 20 near the southern end of the Appalachian Mountains. The 2,063-acre (835 ha) park includes: the John Wesley Hall Grist Mill; the May Plantation Cotton Gin House; and the Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama.

The Thomas Iron Company was a major iron-making firm in the Lehigh Valley from its organization in 1854 until its decline and eventual dismantling in the early 20th century. The firm was named in honor of its founder, David Thomas, who had emigrated to the United States in 1839 to introduce hot blast iron making in the Lehigh Valley, and now embarked on an independent ironmaking venture. The company's main and original plant was in Hokendauqua, Pennsylvania, which grew up around it; it also came to own blast furnaces and railroads elsewhere in the Lehigh Valley and mines in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Changes in the iron industry in the early Twentieth Century left Thomas Iron struggling to compete, and after a failed attempt at modernization and revival from 1913 to 1916, the company's assets were sold and largely dismantled during the 1920s.

The Catasauqua and Fogelsville Railroad was built in the 1850s to transport iron ore from local mines in Lehigh and later Berks County to furnaces along the Lehigh River. Originally owned by two iron companies, the railroad later became part of the Reading system, and parts of it remain in operation today.

Lock Ridge Park is a park built around a historic iron ore blast furnace just outside Alburtis, Pennsylvania, in the Lehigh Valley region of the state.

Nittany Furnace, known earlier as Valentine Furnace, was a hot blast iron furnace located in Spring Township, Centre County, Pennsylvania, United States. Placed in operation in 1888 on the site of an older furnace, it was an important feature of Bellefonte economic life until it closed in 1911, no longer able to compete with more modern steel producers.

Cornwall Iron Furnace is a designated National Historic Landmark that is administered by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in Cornwall, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania in the United States. The furnace was a leading Pennsylvania iron producer from 1742 until it was shut down in 1883. The furnaces, support buildings and surrounding community have been preserved as a historical site and museum, providing a glimpse into Lebanon County's industrial past. The site is the only intact charcoal-burning iron blast furnace in its original plantation in the western hemisphere. Established by Peter Grubb in 1742, Cornwall Furnace was operated during the Revolution by his sons Curtis and Peter Jr. who were major arms providers to George Washington. Robert Coleman acquired Cornwall Furnace after the Revolution and became Pennsylvania's first millionaire. Ownership of the furnace and its surroundings was transferred to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1932.

Charcoal iron is the substance created by the smelting of iron ore with charcoal.

The Grubb Family Iron Dynasty was a succession of iron manufacturing enterprises owned and operated by Grubb family members for more than 165 years. Collectively, they were Pennsylvania's leading iron manufacturer between 1840 and 1870.

The Royal Ironworks of St John, Ipanema was the first ironworks to be continuously operated in Brazil. It is located in Sorocaba region, near the city of Iperó, state of São Paulo. Ruins of the twin blast furnaces are well preserved and nearby is Fazenda Ipanema, a small settlement.

Catasauqua Creek is an ENE–SSW oriented creek draining 6.6 miles (10.6 km) from springs of the Blue Mountain barrier ridge several miles below the Lehigh Gap in the ridge-and-valley Appalachians located upriver & opposite from Allentown in Lehigh and Northampton counties in Pennsylvania.

The Lithgow Blast Furnace is a heritage-listed former blast furnace and now park and visitor attraction at Inch Street, Lithgow, City of Lithgow, New South Wales, Australia. It was built from 1906 to 1907 by William Sandford Limited. It is also known as Eskbank Ironworks Blast Furnace site; Industrial Archaeological Site. The property is owned by Lithgow City Council. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.